WASHINGTON — An exhaustive, five-year Senate investigation of the CIA’s secret interrogations of terrorism suspects renders a strikingly bleak verdict of a program launched in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, describing levels of brutality, dishonesty and seemingly arbitrary violence that at times brought even agency employees to moments of anguish.

The report by the Senate Intelligence Committee delivers new allegations of cruelty in a program whose severe tactics have been abundantly documented, revealing that agency medical personnel voiced alarm that waterboarding methods had deteriorated to “a series of near drownings” and that agency employees subjected detainees to “rectal rehydration” and other painful procedures that were never approved.

The 528-page document catalogues dozens of cases in which CIA officials allegedly deceived their superiors at the White House, members of Congress and even sometimes their peers about how the interrogation program was being run and what it had achieved. In one case, an internal CIA memo relays instructions from the White House to keep the program secret from then-Secretary of State Colin Powell out of concern that he would “blow his stack if he were to be briefed on what’s been going on.”

A declassified summary of the committee’s work discloses for the first time a complete roster of all 119 prisoners held in CIA custody and indicates that at least 26 were held because of mistaken identities or bad intelligence. The publicly released summary is drawn from a longer, classified study that exceeds 6,000 pages.

The report’s central conclusion is that harsh interrogation measures, deemed torture by program critics including President Obama, did not work. The panel deconstructs prominent claims about the value of the “enhanced” measures, including that they produced breakthrough intelligence in the hunt for Osama bin Laden, and dismisses them all as exaggerated if not utterly false — assertions that the CIA and former officers involved in the program vehemently dispute.

In a statement from the White House, Obama said the Senate report “documents a troubling program” and “reinforces my long-held view that these harsh methods were not only inconsistent with our values as [a] nation, they did not serve our broader counterterrorism efforts or our national security interests.” Obama praised the CIA’s work to degrade al-Qaida over the past 13 years but said the agency’s interrogation program “did significant damage to America’s standing in the world and made it harder to pursue our interests with allies and partners.”

The CIA issued a 112-page response to the Senate report, acknowledging failings in the interrogation program but denying that it intentionally misled the public or policymakers about an effort that it maintains delivered critical intelligence.

“The intelligence gained from the program was critical to our understanding of al-Qa’ida and continues to inform our counterterrorism efforts to this day,” CIA Director John Brennan, who was a senior officer at the agency when it set up secret prisons for al-Qaida suspects, said in a written statement. The program “did produce intelligence that helped thwart attack plans, capture terrorists, and save lives,” he said.

The release of the report comes at an unnerving time in the country’s conflict with al-Qaida and its offshoots. The Islamic State has beheaded three Americans in recent months and seized control of territory across Iraq and Syria. Fears that the report could ignite new overseas violence against American interests prompted Secretary of State John Kerry to appeal to Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., the chairwoman of the Senate committee, to consider a delay. The report has also been at the center of intense bureaucratic and political fights that erupted this year in accusations that the CIA surreptitiously monitored the computers used by committee aides involved in the investigation.

Many of the most haunting sections of the Senate document are passages taken from internal CIA memos and emails as agency employees described their visceral reactions to searing interrogation scenes. At one point in 2002, CIA employees at a secret site in Thailand broke down emotionally after witnessing the harrowing treatment of Abu Zubaida, a high-profile facilitator for al-Qaida.

“Several on the team profoundly affected,” one agency employee wrote at the time, “. . . some to the point of tears and choking up.” The passage is contrasted with closed-door testimony from high-ranking CIA officials, including then-CIA Director Michael Hayden, who when asked by a senator in 2007 whether agency personnel had expressed reservations replied: “I’m not aware of any. These guys are more experienced. No.”

NO CALL FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

The investigation was conducted exclusively by the Senate committee’s Democratic staff. Its release Tuesday is certain to stir new debate over a program that has been a source of contention since the first details about the CIA’s secret prison network began to surface publicly a decade ago. Even so, the report is unlikely to lead to new sanctions or structural change.

The document names only a handful of high-ranking CIA employees and does not call for any further investigation of those involved or even offer any formal recommendations. It steers clear of scrutinizing the involvement of the White House and Justice Department, which two years ago ruled out the possibility that CIA employees would face prosecution.

Instead, the Senate text is largely aimed at shaping how the interrogation program will be regarded by history. The inquiry was driven by Feinstein and her frequently stated determination to foreclose any prospect that the United States might contemplate such tactics again. Rather than argue their morality, Feinstein set out to prove that they did not work.

In her foreword to the report, Feinstein does not characterize the CIA’s actions as torture but says the trauma of Sept. 11 led the agency to employ “brutal interrogation techniques in violation of U.S. law, treaty obligations, and our values.” The report should serve as “a warning for the future,” she says.

“We cannot again allow history to be forgotten and grievous past mistakes to be repeated,” Feinstein says.

The reaction to the report, however, only reinforced how polarizing the CIA program remains more than five years after it was ordered dismantled by Obama.

Over the past year, the CIA assembled a lengthy and detailed rebuttal to the committee’s findings that argues that all but a few of the panel’s conclusions are unfounded. Hayden and other agency veterans have for months been planning a similarly aggressive response.

The report also faced criticism from Republicans on the Intelligence Committee who submitted a response to the report that cited alleged inaccuracies and faulted the committee’s decision to base its findings exclusively on CIA documents without interviewing any of the operatives involved. Democrats have said they did so to avoid interfering with a separate Justice Department inquiry.

‘BLACK SITES’

At its height, the CIA program included secret prisons in countries including Afghanistan, Thailand, Romania, Lithuania and Poland — locations that are referred to only by color-themed codes in the report, such as “COBALT,” to preserve a veneer of secrecy.

The establishment of the “black sites” was part of a broader transformation of the CIA in which it rapidly morphed from an agency focused on intelligence-gathering into a paramilitary force with new powers to capture prisoners, disrupt plots and assemble a fleet of armed drones to carry out targeted killings of al-Qaida militants.

The report reveals the often haphazard ways in which the agency assumed these new roles. Within days of the Sept. 11 attacks, for example, President George W. Bush had signed a secret memorandum giving the CIA new authority to “undertake operations designed to capture and detain persons who pose a continuing, serious threat of violence or death to U.S. persons and interests.”

But the memo made no reference to interrogations, providing no explicit authority for what would become an elaborately drawn list of measures — including sleep deprivation, slams against cell walls and simulated drowning — to get detainees to talk. The Bush memo was a murky point of origin for a program that is portrayed as chaotically mismanaged throughout the report.

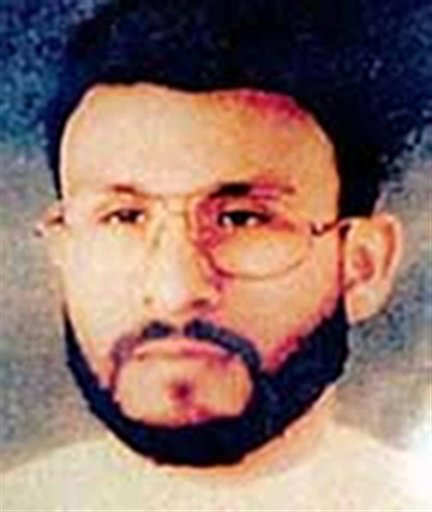

One of the longest sections describes the interrogation of the CIA’s first prisoner, Abu Zubaida, who was detained in Pakistan in March 2002. Zubaida, badly injured when he was captured, was largely cooperative when jointly questioned by the CIA and FBI but was then subjected to confusing and increasingly violent interrogation as the agency assumed control.

After being transferred to a site in Thailand, Zubaida was placed in isolation for 47 days, a period during which the presumably important source on al-Qaida faced no questions. Then, at 11:50 a.m. on Aug. 4, 2002, the CIA launched a round-the-clock interrogation assault — slamming Zubaida against walls, stuffing him into a coffin-size box and waterboarding him until he coughed, vomited and had “involuntary spasms of the torso and extremities.”

The treatment continued for 17 days. At one point, the waterboarding left Zubaida “completely unresponsive, with bubbles rising through his open, full mouth.” CIA memos described employees who were distraught and concerned about the legality of what they had witnessed. One said that “two, perhaps three” were “likely to elect transfer.”

The Senate report suggests top CIA officials at headquarters had little sympathy. When a cable from Thailand warned that the Zubaida interrogation was “approach[ing] the legal limit,” Jose Rodriguez, then chief of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center, cautioned subordinates to refrain from such “speculative language as to the legality” of the interrogation. “Such language is not helpful.”

Through a spokesman, Rodriguez told The Washington Post that he never instructed employees not to send cables about the legality of interrogations.

A WELL-WORN WATERBOARD

Zubaida, also known as Zayn al-Abidin Muhammed Hussein, was waterboarded 83 times and kept in cramped boxes for nearly 300 hours. In October 2002, Bush was informed in his daily intelligence briefing that Zubaida was still withholding “significant threat information,” despite views from the black site that he had been truthful from the outset and was “compliant and cooperative,” the report said.

The document provides a similarly detailed account of the interrogation of the alleged mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who fed his interrogators a stream of falsehoods and intelligence fragments. Waterboarding was supposed to simulate suffocation with a damp cloth and a trickle of liquid. But with Mohammed, CIA operatives used their hands to form a standing pool of water over his mouth. KSM, as he is known in agency documents, was ingesting “a LOT of water,” a CIA medical officer wrote, saying that the application had been so altered that “we are basically doing a series of near drownings.”

The CIA has maintained that only three prisoners were subjected to waterboarding, but the report alludes to evidence that it may have been used on others, including photographs of a well-worn waterboard at a black site where its use was never officially recorded. The committee said the agency could not explain the presence of the board and water-dousing equipment at the site, which is not named in the report but is believed to be the “Salt Pit” in Afghanistan.

There are also references to other procedures, including the use of tubes to administer “rectal rehydration” and feeding. CIA documents describe a case in which a prisoner’s lunch tray “consisting of hummus, pasta with sauce, nuts, and raisins was ‘pureed’ and rectally infused.” At least five CIA detainees were subjected to “rectal rehydration” or rectal feeding without documented medical necessity.

At times, senior CIA operatives voiced deep misgivings. In early 2003, a CIA officer in the interrogation program described it as a “train [wreck] waiting to happen” and that “I intend to get the hell off the train before it happens.” The officer, identified by former colleagues as Charlie Wise, subsequently retired and died in 2003. He had been picked for the job despite being reprimanded for his role in other troubled interrogation efforts in the 1980s in Beirut, former officials said.

The agency’s records of the program were so riddled with errors, according to the report, that the CIA often offered conflicting counts of how many prisoners it had.

In 2007, then-CIA Director Hayden testified in a closed-door session with the Senate panel that “in the history of the program, we’ve had 97 detainees.” In reality, the number was 119, according to the report, including 39 who had been subjected to harsh interrogation methods.

Two years later, when Hayden was preparing to deliver an early intelligence briefing for senior aides to newly elected President Obama, a subordinate noted that the actual count was significantly higher. Hayden “instructed me to keep the detainee number at 98,” the employee wrote to himself in an email, “pick whatever date i needed to make that happen but the number is 98.”

FORMER DIRECTOR SCRUTINIZED

Hayden comes under particularly pointed scrutiny in the report, which includes a 38-page table comparing his statements to often conflicting agency documents. The section is listed as an “example of inaccurate CIA testimony.”

In an email to The Post, Hayden said the discrepancy in the prisoner numbers reflected the fact that detainees captured before the start of the interrogation program were counted separately from those held at the black sites. “This is a question of booking, not a question of deception,” Hayden said. He also said he directed the analyst who had called the discrepancy to his attention to confirm the revised accounting and then inform the incoming CIA director, Leon Panetta, that there was a new number and that the figure should be corrected with Congress.

Hayden said he would have explained this to the committee if given the chance. “Maybe if the committee had talked to real people and accessed their notes we wouldn’t have to have this conversation,” he said, describing the matter as an “example of [committee] methodology. Take a stray ‘fact’ and claim its meaning to fit the desired narrative (mass deception).”

The report cites other cases in which CIA officials are alleged to have obscured facts about the program. In 2003, when David Addington, a lawyer who worked for Vice President Richard Cheney, asked whether the CIA had videotaped interrogations of Zubaida, CIA general counsel Scott Muller informed agency colleagues that he had “told him that tapes were not being made.” Muller apparently did not mention that the CIA had recorded dozens of interrogation sessions or that some in the agency were eager to have them destroyed.

The tapes were destroyed in 2005 at the behest of Rodriguez, a move that triggered a Justice Department investigation. The committee also revealed that a 21-hour section of recordings — which depicted the waterboarding of Zubaida — had gone missing years earlier when then-CIA Inspector General John Helgerson’s office sought to review them as part of an inquiry into the interrogation program.

Helgerson would go on to find substantial problems with the program. But, in contrast to the Senate panel’s findings, his report concluded that the agency’s “interrogation of terrorists has provided intelligence that has enabled the identification and apprehension of other terrorists and warned of terrorist plots planned for the United States and around the world.”

A prominent section of the Senate report is devoted to high-profile claims that the interrogation program produced “unique” and otherwise unobtainable intelligence that helped thwart plots or led to the capture of senior al-Qaida operatives.

Senate investigators said none of the claims held up under scrutiny, with some unraveling because information was erroneously attributed to detainees subjected to harsh interrogations, others because the CIA already had information from other sources. In some cases, according to the panel, there was no viable terrorist plot to disrupt.

A document prepared for Cheney before a March 8, 2005, National Security Council meeting noted in a section titled “Interrogation Results” that “operatives Jose Padilla and Binyam Mohammed planned to build and detonate a ‘dirty bomb’ in the Washington DC area.”

But according to an April 2003 CIA email, Padilla and Mohammed had apparently taken seriously a “ludicrous and humorous” article about building a dirty bomb in a kitchen by swinging buckets of uranium to enrich it.

KSM dismissed the idea, as did a government assessment of the proposed plot: “CIA and Lawrence Livermore National Lab have assessed that the article is filled with countless technical inaccuracies which would likely result in the death of anyone attempting to follow the instructions, and definitely would not result in a nuclear explosion,” noted another CIA email in April 2003. The agency nonetheless continued to directly cite the “dirty bomb” plot while defending the interrogation program until at least 2007, the report notes.

A “COCKAMAMIE” DIRTY-BOMB PLOT

The report also deconstructs the timeline leading to the identification of Padilla and his alleged accomplice. It notes that in April 2002, Pakistani authorities, who detained Padilla, suspected he was an al-Qaida member. A few days later, Zubaida described two individuals who were pursuing what was described as a “cockamamie” dirty-bomb plot. The connection was made by the CIA immediately, months before the use of harsh interrogation on Zubaida.

Some within the CIA were derisive of the continuing exploitation of the dirty-bomb plot by the agency. “We’ll never be able to successfully expunge Padilla and the ‘dirty bomb’ plot from the lore of disruption, but once again I’d like to go on the record that Padilla admitted that the only reason he came up with so-called ‘dirty bomb’ was that he wanted to get out of Afghanistan and figured that if he came up with something spectacular, they’d finance him,” wrote the head of the Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear group at the CIA Counterterrorism Center. “Even KSM says Padilla had a screw loose.”

In the CIA’s rebuttal, which was delivered in 2013 to the Senate but released publicly on Tuesday for the first time, the agency acknowledged that it took “too long to stop making references to his infeasible ‘Dirty Bomb’ plot” but said Padilla was a legitimate threat and “a good example of the importance of intelligence derived from the detainee program.”

In another high-profile case, the CIA credited the interrogation program with the capture of Hambali, a senior member of Jemaah Islamiah and the suspected mastermind of the 2002 Bali bombing, which killed more than 200 people. In a briefing for the president’s chief of staff, for instance, the CIA wrote, “During [KSM’s] interrogation we acquired information that led to the capture of Hambali.” But the Senate found that information from KSM played no role in Hambali’s capture and that, in fact, information leading to his detention came from signals intelligence, a CIA source, and investigations by the Thai authorities.

Similarly, the CIA said the interrogation program led to the discovery of the “Second Wave” attacks, a plan by KSM to employ non-Arabs to use airplanes to hit targets on the West Coast. Associated with this in CIA reporting was the identification of al-Ghuraba, a cell of the Southeast Asian militant group Jemaah Islamiah.

In a November 2007 briefing for Bush on “Plots Discovered as a Result of EITs,” or “enhanced interrogation techniques,” the CIA said it “learned” about the Second Wave and al-Ghuraba “after applying the waterboard along with interrogation techniques.” But the Senate report says the plot was disrupted by a series of arrests and interrogations that had nothing to do with the CIA program.

Even the hunt for bin Laden was accompanied by exaggerations of the role of brutal interrogation techniques, according to the report. In particular, the committee found that the interrogations played no meaningful role in the identification of a courier, Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, who would lead the agency to bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

The CIA’s document reiterates its claim that coercive measures helped, saying the tactics led two detainees in agency custody, Ammar al-Baluchi and Hassan Ghul, to provide important clues to the courier. Baluchi was the first to identify Kuwaiti as bin Laden’s messenger, and did so only “after undergoing enhanced interrogation techniques.”

Ghul, who was captured in Iraq, went even further, confirming under coercive pressure that Kuwaiti had delivered a letter from bin Laden to another al-Qaida operative and had vanished along with the al-Qaida chief in 2002.

But the committee cited CIA records showing that Ghul’s revelations came before he was subjected to harsh measures. In an interview with the CIA inspector general’s office, a CIA officer familiar with Ghul’s case said that he “sang like a tweetie bird. He opened up right away and was cooperative from the outset.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story