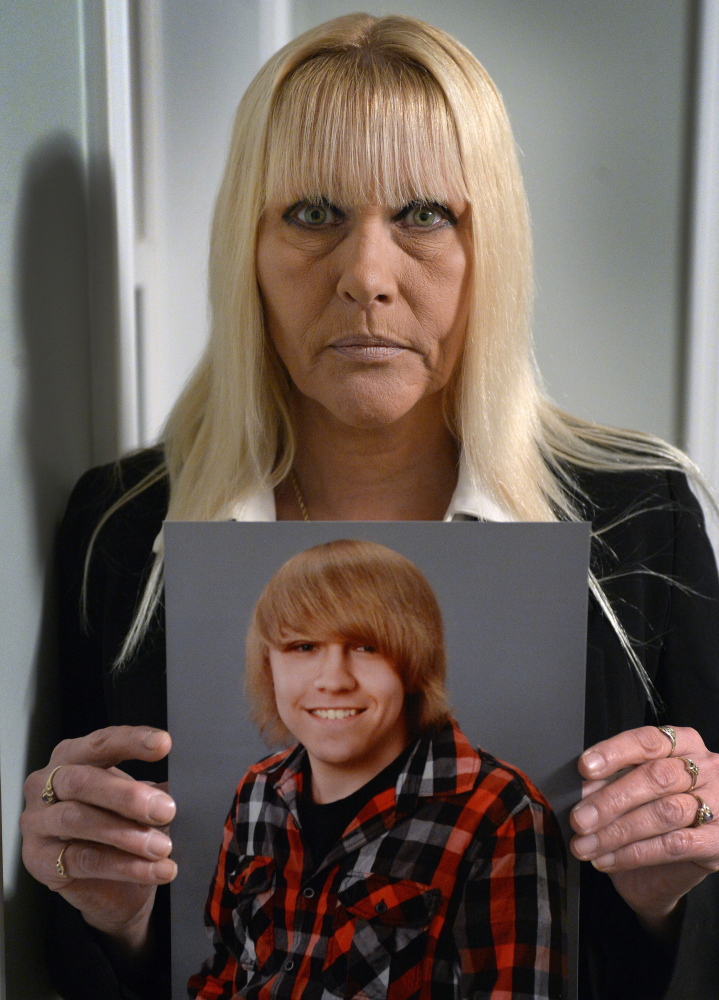

BIDDEFORD — Dylan Collins’ mother always knew her son’s prospects in life were limited by his developmental delays and behavioral problems.

But Donna Pitcher hoped he’d progress enough through special education programs and her constant help to have some semblance of a normal life: hold a job, get married, go on vacations and have friends.

“I wanted him to have a happy childhood and a happy adulthood,” she said. “I knew he was limited in his ability to achieve, but I didn’t believe that was lifelong. Sometimes people blossom in their 30s. Who knows?”

But those dreams died at the beginning of this year, when Collins’ behavior took an abrupt turn for the worse. Pitcher had him committed to Southern Maine Health Care’s mental health ward twice, once overnight as a juvenile and again for a month after he became an adult, before she made the last of many calls to police that led to her son’s arrest this month on two counts of murder and one count of arson.

Collins did not know James Ford and Michael Moore, the two young men he is accused of killing. But his increasingly troubled life intersected with theirs Sept. 18, when police say Collins set fire to the multifamily building at 35 Main St. in Biddeford where Ford and Moore lived, trapping the two friends in their attic apartment as it filled with smoke. Moore died the day after the fire. Ford died a month later from infections brought on by the toxic chemicals in the smoke he inhaled.

Authorities have released no information on what led them to charge Collins with arson and murder, nor have they cited a possible motive.

Interviews with Collins’ mother, one of his high school friends and Ford’s half sister reveal that, to their knowledge, Collins had never crossed paths with Ford or Moore before that night. But both Collins’ mother and his friend said he knew a woman who also lived in the building.

There had been plenty of signs that something was wrong with Dylan Collins. And those signs began to emerge many years before the fire that killed two young men.

“There were these interim times when it was a very good thing to be Dylan’s mom. It was a proud thing. It was a happy thing,” Pitcher said. “I’ve always missed those times when he would go the other way. He would take two really great steps forward, then 10 bad steps backwards. But I would remember the two steps forward and try again and try again and try again just to get back there.”

DIFFICULT EARLY YEARS

Pitcher spoke with the Maine Sunday Telegram during a two-hour interview at the law offices of her son’s attorneys, Fairfield & Associates in Lyman, where she arrived with a crate of childhood photos of Collins. Although Collins’ attorneys, Amy Fairfield and Will Ashe, were present during the interview, Pitcher spoke mostly uninterrupted, describing her son’s development from infancy – and his struggles.

Collins was Pitcher’s fourth child, her only son after three daughters by a different father. She raised Collins by herself, while her daughters split time between her and their father.

Early on, Collins was the “easiest” child. As a baby, he slept through the night and adjusted easily to feeding schedules and potty training.

“At about 4 or 5 that all seemed to change. He had a very difficult time transitioning, even to taking a bath or leaving the home or going to the dinner table, and he started becoming very resistant to any kind of changes,” Pitcher said.

Around that time, Pitcher noticed her son also developed what she described as “seizurelike symptoms,” rapidly blinking his eyes and moving his mouth without being aware of it.

They were living in Waterboro at the time, and she took him to a children’s services agency in Arundel to be evaluated. Doctors put Collins through a battery of examinations, took blood samples and ran CAT scans, finding possible signs of autism and Tourette’s syndrome but nothing conclusive.

“When the physical stuff started happening, that’s when I knew something serious was going on here. And I’m scared. I’m scared for him. I don’t know if he’s going to have a seizure,” Pitcher said. “They said because they couldn’t put their finger on the exact one, they couldn’t treat him.”

During this time, Pitcher said she would often receive phone calls from Collins’ day care providers, telling her to pick him up because he was too disruptive and couldn’t be managed.

“Dylan did improve,” she said. But before that, “he was thrown out of a lot of day cares. He was thrown out of first grade. It was the same things: not willing to stay with the group, not willing to transition when the group transitioned.”

Pitcher said her son showed progress after being moved from a mainstream public school to a day program, run by the mental health agency Sweetser, for children with behavioral problems or emotional disturbance.

“He really made a big step and seemed to stay that way,” she said. “He did well in school and he was happy there. And we had some years of, you know, real bliss, just relief.”

‘HE JUST STOPPED TALKING’

He transitioned back to a special education program in a Waterboro public school and did well there before finances forced Pitcher to move her family to Biddeford.

As a special education student at Biddeford Middle School and Biddeford High School, Collins did poorly. His grades never rose above C’s and D’s.

“Dylan had problems right off the bat,” his mother said. “He was not accepted. He was taunted. He was physically hit, pushed, threatened and he ended up fighting back eventually.”

She transferred him to Alternative Pathways Classroom, a specialized school in Biddeford, where Collins made friends. His grades steadily improved, and he earned A’s and B’s by the end of his senior year.

But suddenly his personality darkened, and he stopped talking. In January, Collins used a blade to slice open his left arm.

“There was no warning,” Pitcher said.

Alisha Atwater, a former classmate at Alternative Pathways Classroom, said she and Collins had been friends before his abrupt change in behavior. They were in an English class together and began chatting. She said Collins was shy, quiet and polite but would laugh easily.

“He was really smart,” Atwater said. “He didn’t talk a lot, but he knew what he was doing in school.”

But something happened at the beginning of the year. Collins stopped talking to everyone. After his 18th birthday in March, he dyed his blond hair black and started wearing only dark clothing.

“I don’t know what happened,” Atwater said. “He just stopped talking after that.”

SOUNDING THE ALARM

On July 27, Pitcher discovered her son had begun making bombs in his bedroom and was researching mass murders. She called police. A police log says she told them she found “knives, flammables and bomb-making materials” all over the apartment they shared at 37 Graham St.

Pitcher said she called 911 several times this year – both before the fire and after – because she was concerned about her son’s deteriorating mental state. She also said she had called police several times – she does not remember how many – when Collins was a juvenile.

She had him hospitalized in January after finding long, self-inflicted cuts on his left arm that he told her he had done with a friend. He was held overnight at Southern Maine Health Care’s mental health ward that time.

After finding the bomb-making materials in his bedroom in July, she had Collins – then 18, legally an adult – admitted for a monthlong psychological evaluation at Southern Maine Health Care again.

Pitcher said she tried all summer to have her son committed to a psychiatric facility, believing Collins was a serious threat to himself or others. But SMHC released him Aug. 28 after medical staff declined to seek a court order to have Collins committed to Riverview Psychiatric Center in Augusta.

“I did everything I could to sound the alarm,” Pitcher said.

Sue Hadiaris, a spokeswoman at Southern Maine Health Care, said she was unable to confirm whether Collins had been admitted to the hospital, citing patient confidentiality.

Those who work with the mentally ill in Maine say it’s not easy to commit an adult to a mental health facility against his will. The threshold for involuntary commitment is high, generally requiring several mental health professionals and a judge to assess whether someone has a mental illness and whether he poses a danger to himself or others.

Atwater said she saw Collins shortly before his hospital stay and was troubled by the exchange.

“Before he went to the hospital, I ran into him on the street, and he said, ‘I’m not good.’ And he said, ‘Can I have a hug?’ and I thought that was really weird,” she said.

LEADING UP TO THE ARREST

Those who knew Collins have not been eager to talk about him since the fire. School officials in Biddeford declined to speak about Collins. The former landlady of Pitcher and Collins on Graham Street also declined to comment for this story. His roommate on Center Street, where he lived for only days before his arrest, also declined to talk about him.

But Collins’ posts on his Facebook account showed an increasing sense of anger, depression and isolation. “From now on the only people I need in life are friends. Period the end,” he wrote on Aug. 22.

Pitcher said her son had friends who may have influenced his behavior, including a woman he knew who lived at 35 Main St., the building Collins is accused of setting on fire. Fairfield, Collins’ attorney, stopped Pitcher from elaborating about that woman.

Atwater, too, said Collins knew a woman who lived at 35 Main St., but she said she knew few details about their relationship, including the woman’s name.

Maine State Police spokesman Stephen McCausland declined to comment on any details of the case.

After the fire, Pitcher called Biddeford police three more times, beginning Oct. 14, when she told them that Collins had ordered a passport online and that she wanted help stopping her son.

On Oct. 20, Pitcher walked into the Biddeford police station to report that Collins had threatened to punch her if she didn’t leave their home.

Collins’ Facebook posts grew darker.

“I don’t care if I die, it’s not a world worth living in anyway,” he wrote in a post on Oct. 26.

“I don’t deserve the hatred,” he wrote on Oct. 31.

Pitcher’s final call to police, on Nov. 5, led to his arrest on charges that he set the fire that killed Ford and Moore. Pitcher declined to say what she told police in that call.

MENTAL STATE WILL BE ‘AN ISSUE’

Biddeford Deputy Police Chief JoAnne Fisk declined to release the police reports for each of Pitcher’s calls, saying it was up to the Maine Attorney General’s Office, which is prosecuting Collins, to determine whether those reports are a public record.

Assistant Attorney General John Alsop last week denied a request filed by the Telegram under the state’s Freedom of Access Act to release the reports. Alsop said in a Nov. 21 letter that the reports are confidential and that releasing them would interfere with law enforcement proceedings, interfere with the court’s ability to convene an impartial jury and would be an unwarranted invasion of privacy.

“His mental state will be an issue at trial,” Alsop wrote. “Events occurring recently at the jail underscore the importance and sensitivity of the defendant’s mental state. The requested reports pertain directly to his mental state that is subject to continuing investigation.”

A state police affidavit used to obtain a warrant for Collins’ arrest has been ordered sealed by a judge, as have search warrant affidavits in the case.

Pitcher said she believes that her son, even in jail, remains a threat to himself and others, and that he needs help.

Indeed, the day after her interview with the Telegram, Pitcher wrote in a Facebook message Nov. 20 that “something horrible has happened.”

Collins attempted suicide at the York County Jail in Alfred, where he has been held without bail since his arrest, by leaping 10½ feet off a second-floor stairway.

“He has multiple facial fractures, multiple skull fractures, swelling and blood and fluid on his brain,” Pitcher said in a Facebook message after visiting her son at Maine Medical Center in Portland. “He cannot open or see out of his right eye and the bone above it is broken. He may lose all his top teeth and has multiple jaw fractures. He has fractures to his right hand, wrist, elbow and knee cap. He has an undetermined neck injury.

“He said to me, ‘It was my only way out of this hell.’ “

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story