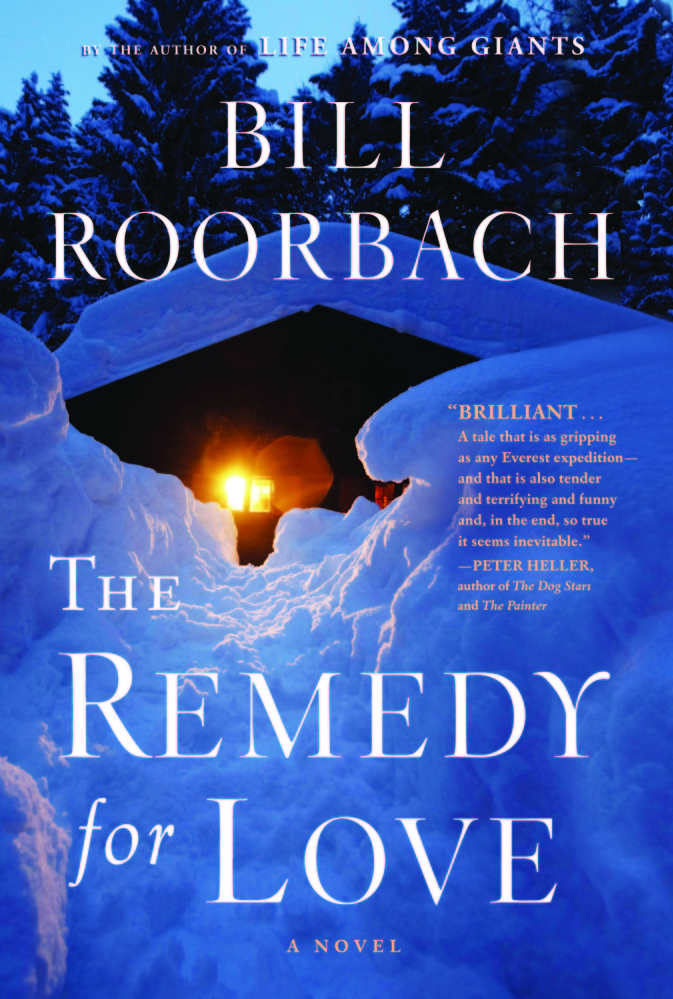

Bill Roorbach’s latest novel, “The Remedy for Love,” hangs perilously between two distant lines spoken by one of the book’s central characters.

Danielle is an odd, disheveled young woman who refers to herself occasionally as a “ghost.” Eric is a bit of an obsessive, well-meaning lawyer with a compulsive sense of responsibility for others.

The two meet randomly in a Hannaford checkout line in a small Maine town as the first flakes of an expected “storm of the century” dim the late afternoon light.

By the time Danielle delivers one line, the two are snowbound – if not buried – in a rustic cabin along the cleft of a river, thick in the middle of the storm. As she and Eric open up to each other about their own intimate relationships and heartbreaks, she tells him they are “refugees” from love, recasting them after her previous pronouncement that they were “survivors.”

Earlier in the novel, she recites a line from Henry David Thoreau about his own heartbreak in love, that “the only remedy for love is to love more.”

The two lines ratchet up the book’s tension, such that if it were a sound, it would be an ear-splitting whistle from a blistering teakettle.

Being snowbound can be high adventure, but in Roorbach’s tale, it is slow submersion into the darkest, hidden corner where love hides after being gravely wounded.

Roorbach, who lives in western Maine, is at the top of his literary game here. He is masterful in inviting readers along, allowing them to slowly get to know these two strangers as they get to know one another. Roorbach said recently in a talk about the book that it was harder for him, as a writer, to get to know Danielle. That’s evident in Eric’s slow entrance into any true and deep understanding of this strange creature.

In Roorbach’s deft hands, however, this process of artistic discovery is not a deficiency. It adds a dimension of fidelity to the oh-so-human process of discovery that we all have to go through in coming to know another. The mystery of this sullen and withdrawn, yet at times vibrant, funny and smart woman sucks you along as it threatens to tear your heart apart.

Eric is much more transparent, even to himself. He knows he’s a sucker for taking care of the misbegotten.

He continues to pine for his soon to be ex-wife, after she leaves him for another man, planning monthly dinners he’ll cook for her when they get together.

The irony does not escape him that first night he and Danielle spend in the cabin. He is aware as he prepares dinner for the two of them from the groceries he’d just bought at Hannaford that this was the meal he had hoped to cook for his wife – knowing that, once again, she wouldn’t have come to his table.

Eric is yin to Danielle’s yang. She is unpredictable; he is not. But that is not to say that either of them are beyond the ability to stretch into new territory, to make themselves vulnerable again to contemplate loving another.

Roorbach’s “The Remedy for Love” is a deep exploration of the dangers of intimacy. Most everyone has had to face the fallout of such risks.

The novel puts readers in what can feel like an inescapable place, surrounded by the soul-crushing damage that falls like the ruins of an earthquake – or perhaps a blizzard – leaving you a survivor and a refugee at once.

It provides a glimpse at just how daunting it can be to navigate out of the darkness of one relationship, into the light of another.

Frank O Smith is a Maine writer whose novel, “Dream Singer,” was released in October. It was a finalist for the Bellwether Prize, created by best-selling novelist Barbara Kingsolver “in support of a literature of social change.” Smith can be reached via frankosmithstories.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story