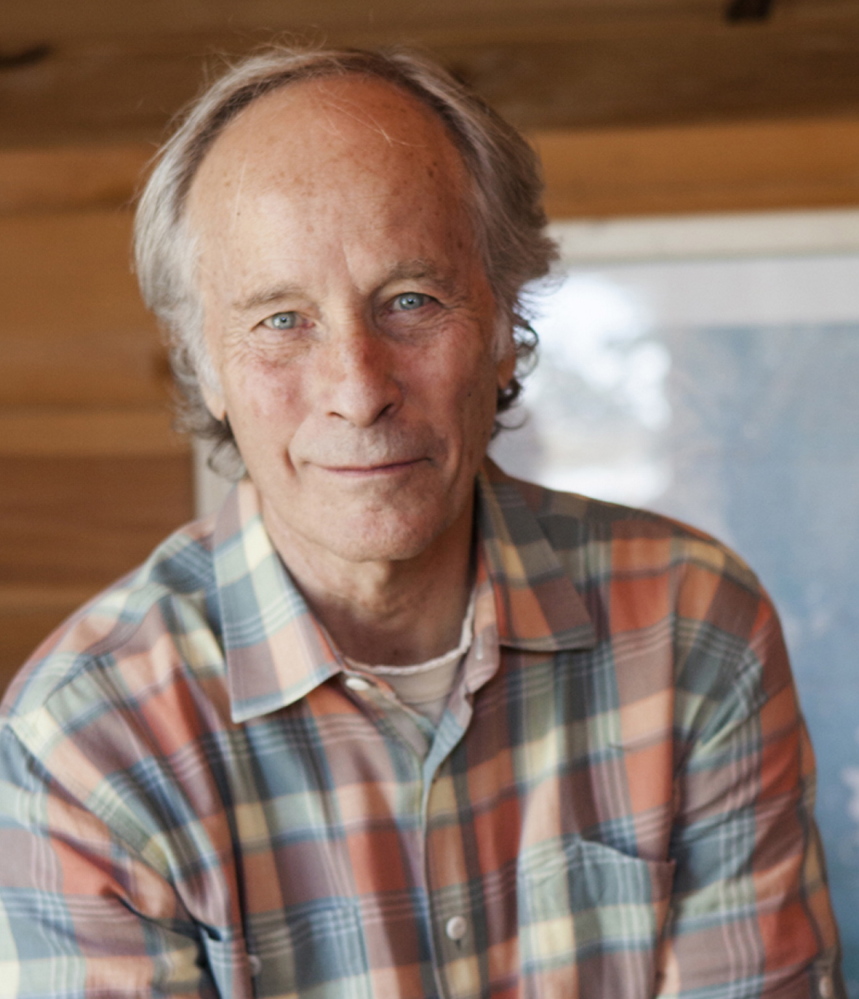

Maine author Richard Ford is back with a new take on an old familiar character.

Frank Bascombe, the iconic anti-hero of Ford’s acclaimed trilogy, first appeared in “The Sportswriter” in 1986, followed by the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “Independence Day,” and finally “The Lay of The Land.” After that last installment, Ford said he was putting Frank Bascombe to rest. Luckily for us, he changed his mind.

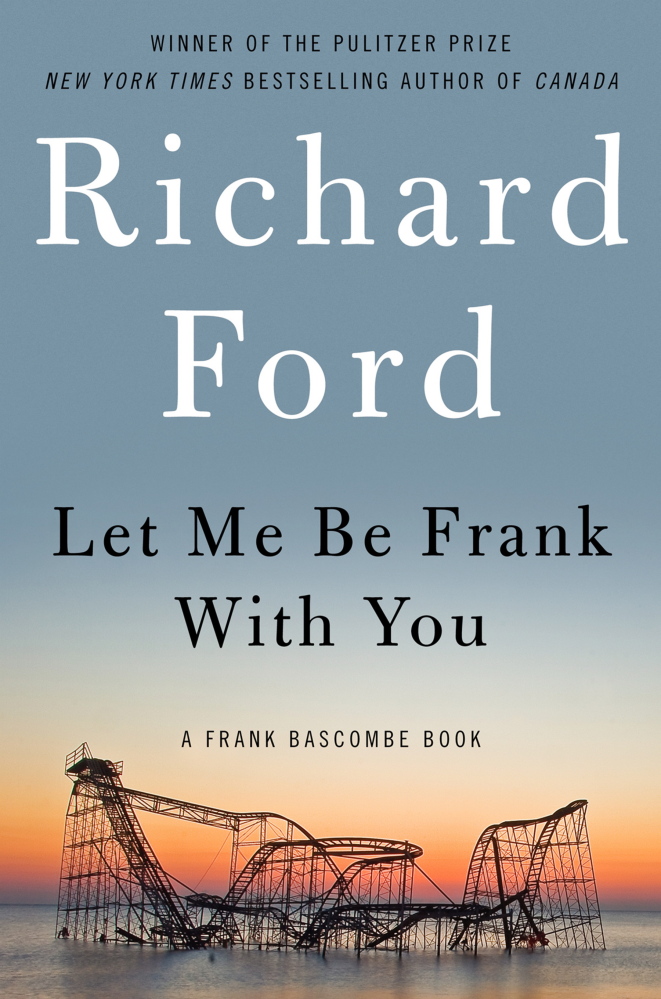

His new book, “Let Me Be Frank With You” is a collection of four linked novellas that render shrewd, often biting, appraisals of family, aging and the vagaries of modern life.

In his latest incarnation, sportswriter-turned-realtor Frank, now 68, is living with his second wife, Sally, on the Jersey Shore, puzzling over the meaning of retirement. Once a week he greets troops returning from Afghanistan and Iraq, and he reads for the blind. Sally works as a grief counselor, helping seniors cope with unspeakable loss. The loss in question resulted from Hurricane Sandy, which forms the backdrop for these razor-sharp stories. Each novella is linked to the storm, lending a suitable air of misery for Frank’s prickly ponderings.

“Life’s a matter of gradual subtraction,” he muses, and in ways both large and small, it’s one of the book’s dominant themes. Frank wants less drivel, more authenticity in his dealings. So he starts an inventory of polluted words and phrases – bonding, sibs, awesome – that should be expunged from our speech. This becomes a running gag throughout the book, with worn-out lingo gathering like dustballs.

Yet the theme of loss – of homes yanked off their foundations and people unmoored – is inescapable, setting up the balancing act in these tragicomic tales.

In the opening novella, “I’m Here,” Frank gets a call from a former client whose beach house, once owned by Frank, has become a casualty of the storm. He wants Frank’s advice on whether to accept a paltry offer on what’s left of the property.

“Everything’s more real if two can see it,” Frank says.

Ford mines the situation for all its richness. The client, who has had more than a little work done to achieve his new “repurposed ‘look,'” becomes an unwitting object of Frank’s skewering.

“Arnie looks like somebody who used to be Arnie Urquhart,” Ford writes. “Age and change have left him squirrelly and unpredictable – to himself.”

Later there’s a scene in which Frank, panicking, tries to dodge a nascent hug from the client, which provides a madcap moment of self-parody.

One quickly discovers that the world according to Frank – and Ford – has its own rules and conventions. This is that most interior of books where relatively little happens by way of action. Instead the stories deal in aftermath – the rebuilding of lives after a storm. Which also proves to be a metaphor for other, previous losses, such as the death of Frank’s young son years earlier and the subsequent unraveling of his first marriage.

This is weighty material, to be sure, for which Ford has created a nearly transparent narrator. Frank is the human embodiment of a thought bubble, endlessly ruminating, often in gorgeous prose. His outlook, by turns squirming, playful, cranky, fatalistic and big-hearted, becomes life-affirming, even amid havoc and loss.

The beauty of this book lies in its encompassing humanity, its juxtaposition of gravity and wit, and the flawed duality of our protagonist. Ever the gentleman, Frank says one thing while thinking another, mindful of people’s feelings while incessantly monitoring his own. Since much of the book chronicles the tangle of Frank’s inner life, we witness his thoroughly human ways of being in the world. As a result, Ford illuminates parts of us all.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story