The specter of an Ebola outbreak in the United States, no matter how unlikely, has led some states to take the extraordinary step of requiring an entire group of people to be quarantined even though the risk they pose to the public may be remote.

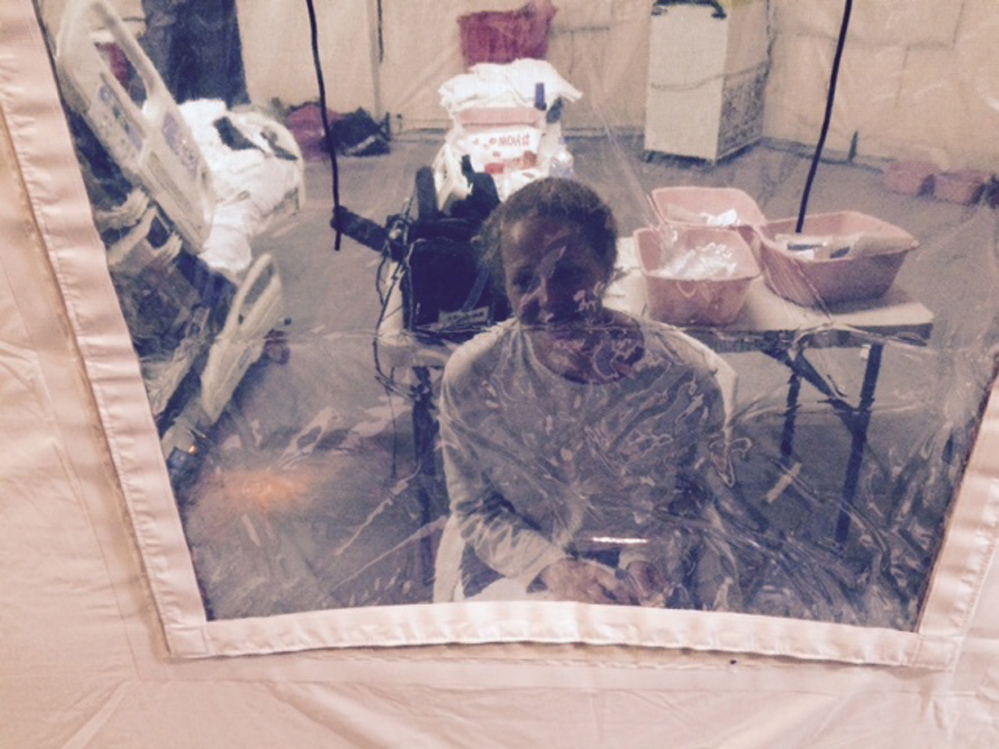

That situation has led to a potential showdown between Kaci Hickox and Maine officials over whether the nurse can be quarantined against her will. Hickox was previously isolated in a special tent at University Hospital in New Jersey after she returned to the U.S. on Friday from treating Ebola patients in West Africa. She was the first person affected by the mandatory quarantine that New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie had imposed for anyone entering the state who had worked with Ebola patients.

Hickox, who worked in Sierra Leone for Doctors Without Borders, shows no symptoms of Ebola, which is necessary to transmit the potentially fatal disease, but Maine health officials say if she does not abide by the quarantine, they will seek a court order to enforce it.

The issue highlights the conflict between an individual’s civil rights and the public’s expectation that the government will do what it must to keep them safe.

“Normally one can’t be locked up without suspicion of a crime or conviction, but because infections are catching and because they can be spread by people who are not visibly sick, the state has the right to protect society from disastrous consequences by temporarily limiting someone’s liberties,” said Eugene Kontorovich, a constitutional law scholar at Northwestern University Law School in Chicago.

Health officials in the U.S. have a long history of taking steps in the interest of public health, including closing schools and ordering large-scale quarantines, such as the one imposed during the 1918 influenza epidemic that was credited with limiting the spread of the disease.

By contrast, a requirement in 1900 that Chinese residents in San Francisco be inoculated and quarantined after an outbreak of a plague was overturned by the courts.

Courts have generally sided with the state in instances when civil liberties are pitted against public health, Kontorovich said.

Some public health experts say aggressive, widespread quarantines may be illegal if they are not based on medical evidence, and can be counterproductive because they could lead people to hide their potential exposure or travel history. In the current environment, they also could dissuade health care workers from volunteering to fight Ebola in West Africa, where the epidemic is threatening to spread beyond a few impoverished countries.

Quarantines also create unnecessary fear.

Arthur Caplan, founding director of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center, said that by imposing a quarantine, even a voluntary one, it’s sending a message to the public that there’s something to fear when there isn’t.

“No state has made it clear how they would enforce a quarantine,” he said. “If (Hickox) leaves the house, are they going to shoot her? Are they going to Taser her? Is there going to be a guard at her door dressed in a moon suit?”

Governors in New Jersey, New York and Illinois – all with international airports – announced policies last week that call for health care workers and others who have been in close proximity to people with Ebola to remain in quarantine for 21 days, the maximum period it could take for someone infected with the disease to start showing symptoms.

Now, several other states have announced measures that go beyond the recommendations of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which says people should be monitored for symptoms but not confined.

The federal CDC also no longer uses the word “quarantine” in its Ebola protocols for people at risk. However, states have their own authority to take steps to protect public health.

“Public health law is all state-based, so where the balance (between civil liberties and public health) lies is all state-based,” said Amy Major, associate director of the Center for Health and Homeland Security at the University of Maryland.

“You have to have certain due-process opportunities. You have to be able to challenge the order and appeal it,” Major said.

The situations that might trigger restrictions on people’s movements are written broadly so health officials can be responsive to each particular situation. Although it has a high mortality rate, Ebola is difficult to contract. Typhoid, by comparison, may be carried by someone who is not at all sick but can infect everyone the carrier comes in contact with.

Health officials also make a distinction between isolation, in which a sick person is allowed no contact with others, and quarantine, in which a person is potentially sick but hasn’t been confirmed to have the disease. They are allowed contact with others.

Voluntary quarantine is a step that is much less demanding on the health infrastructure than isolating someone at a medical facility, and it also assures that the individuals have their basic needs met, Major said. One of the primary objections to Hickox’s detention in New Jersey was that she couldn’t have access to anyone, didn’t have a television and had almost no comforts, such as a flush toilet.

“If you put someone in that limited movement restriction, you need to support their basic needs,” she said.

In Maine, state law allows the Department of Health and Human Services to confine a person “reasonably believed to have a communicable disease,” but requires a court order.

“Upon the department’s submission of an affidavit showing by clear and convincing evidence that the person or property which is the subject of the petition requires immediate custody in order to avoid a clear and immediate public health threat, a judge of the District Court or justice of the Superior Court may grant temporary custody of the subject of the petition to the department and may order specific emergency care, treatment or evaluation,” the law says. The court can take measures it deems necessary for public safety pending a hearing on the petition.

Maine has used its power before: In 2006, the state obtained an arrest warrant for a 54-year-old homeless man with tuberculosis, a highly contagious airborne disease, because officials could not be sure he was taking his medicine to prevent the disease’s spread. The man had stopped once before and spread a drug-resistant form of the disease to three other people. He was held in jail until he could be transferred to a medical facility with a TB unit.

The Maine law seeks to balance a person’s civil rights with the public welfare, but the state needs to establish a compelling case to deprive someone of their liberty, said Alison Beyea, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union in Maine.

“Maine law allows for some restrictions to take place when we have an actual or threatened epidemic of disease. At this stage we’re not there. There’s no justification for mandatory quarantine at this point,” she said. “This is a medical issue and we need to be guided by medical science and not by fear.”

But Kontorovich, the law scholar, said the question of what steps should be taken to prevent the spread of disease is not strictly a medical one.

“Science could say what the potential risk is. The question is how do you value that risk? Even if they say there’s very little chance, they can’t say how much that risk is worth and they can’t say how much the inconvenience (of quarantine) is worth,” Kontorovich said. “It’s not a science question. It’s a policy question,” one appropriately left to elected politicians, he said.

The current public mood appears to favor mandatory quarantines, driven in part by the lethality of the disease in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea and its rapid spread through undeveloped areas there. More than 10,000 people have contracted the disease in West Africa and almost 5,000 have died, according to the federal CDC.

Public health officials, however, note that those countries lack the health infrastructure needed to help someone recover from the disease, techniques like providing intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration and therapies to keep bodily organs working until the disease is under control. In Dallas, the second of two health care workers who contracted the disease while treating an Ebola patient from Liberia was released from the hospital Tuesday after testing negative for the disease.

The only fatality in the U.S. has been Thomas Eric Duncan, who had contracted the disease in Liberia and was already ill when he reported to the hospital in Dallas.

Kontorovich believes the altruism that leads people to help fight the disease in Africa also should help them understand the public health concerns at home.

“It’s very noble that people want to go to Africa and help treat people there,” he said. “Surely the thing to do is to extend that to taking the measures our elected government officials believe are suitable to prevent introduction of the disease to the United States.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story