Every year at this time I think about appropriate Halloween music. There are all the usual suspects: “Night on Bald Mountain,” Verdi and Mozart for hellfire and damnation, Beethoven for the dark night of the soul, Grieg for trolls, Chopin for autumn leaves and funerals, Mahler for schadenfreude, and “Symphonie Fantastique,” which the Portland Symphony Orchestra will be playing next month.

But the all-time winner for music that provides that special scary thrill is Henry Cowell’s “Banshee” for piano. It’s a short piece for prepared piano, which John Cage learned from Cowell, but makes up for length in intensity and, well, realism. There really is a demon inside that piano.

I’ve been reading about and listening to Cowell since hearing his Quartet No. 4 (“United”) played by the Portland String Quartet earlier this month. I’ve even bought some of his piano music, featuring his invention of “tone clusters,” or groups of minor second chords played with the fist or the forearm, thinking my grandson would like to play them. (Béla Bartók, whom kids also love, requested Cowell’s permission to use the technique in his own works.)

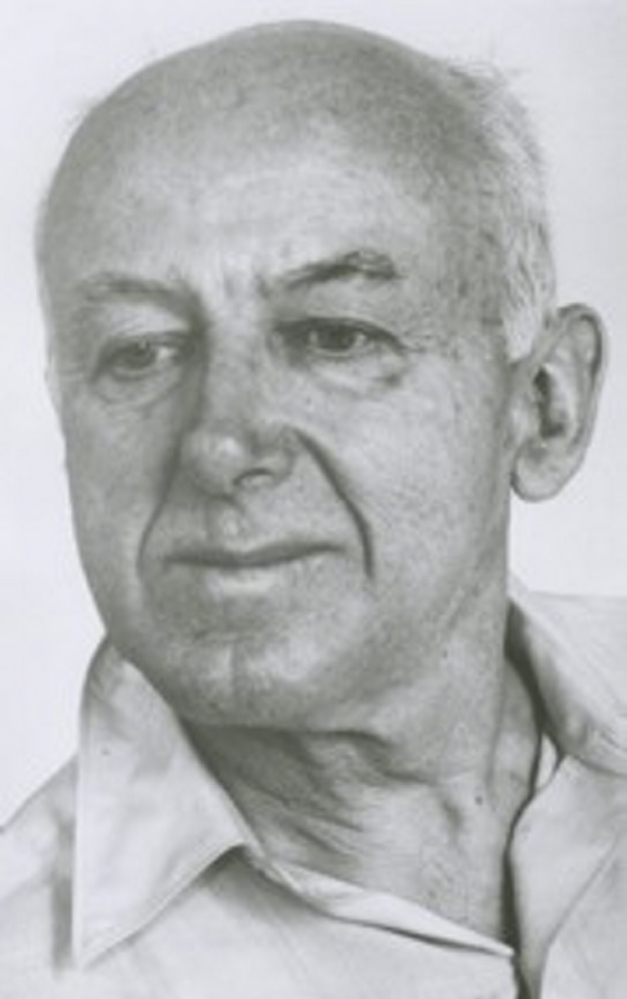

Cowell, born in California in 1897 of philosophical anarchist parents, is one of a long line of quirky American composers of genius, beginning with the New England writer of hymns and fuguing tunes William Billings, who thought that there should always be twice as many basses as any other voice in the choir. (He was dead on.)

Homeschooled until the age of 17, Cowell was largely self-taught in music until he began to study at the University of California, Berkeley, under Charles Seeger, father of Pete Seeger, who recognized and nurtured his genius.

The list of Cowell’s achievements goes on and on. He wrote more than 1,000 compositions, including 180 songs. He was a writer whose prose, as well as his music, strongly influenced generations of composers, including both John Cage and George Gershwin. He was an ethnomusicologist who learned many of the world’s musical traditions and incorporated them into his own work, not quoting, but grafting his ideas on to their roots.

Arnold Schoenberg asked him to play for his composition class in Vienna.

Cowell worked with Leôn Theremin on machines that would realize his ideas about the relationship of harmony and rhythm. He invented rhythms so complex that they could not be played by a human being, but only by a specially designed instrument called a Rhythmicon.

He championed American Indian music, which is nothing like what Antonín Dvorák imagined, or what any of us can imagine, more strange and “foreign” than anything recorded in far-off lands.

He wrote some of his best work from a cell in San Quentin.

It is hard to believe in today’s society, but in 1936 Cowell was sentenced to 15 years in prison for having a homosexual relationship. He served four years and eventually received a full pardon from the governor of California, but the experience profoundly affected him. Opinions differ about whether he was a broken man. He never spoke about radical politics again and may have made his works more accessible to a wide audience, but that also may have been a natural development with age.

The imprisonment, because of lingering prejudice, prevented his works from receiving the recognition they deserved and still deserve.

A good dose of Cowell is just what is needed to improve audience reaction to “modern” music. His work is accessible, interesting, inventive, melodic and non-academic. He wrote a lovely piano concerto and 15 symphonies, any one of which would grace a Portland Symphony Orchestra concert. The full cycle has never been recorded. There’s an opportunity for someone.

Christopher Hyde is a writer and musician who lives in Pownal. He can be reached at:

classbeat@netscape.net

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story