WASHINGTON — Every airline passenger who arrives in the United States from one of the three West African nations hardest hit by Ebola will be monitored by state and local health authorities for 21 days, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Wednesday.

The travelers will be required to report their temperature daily and call a state hotline if they show any symptoms of the illness. The program will begin Monday in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Maryland and Virginia, and expand to other states later, CDC Director Thomas Frieden said.

“We’re tightening the process by establishing active monitoring of every traveler who returns to this country from one of the three infected countries,” Frieden said in a conference call with reporters.

The monitoring plan was the administration’s latest step to intercept travelers who may have been exposed to the lethal virus in the three countries affected most by the outbreak — Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Fending off critics who have demanded an outright entry ban on people traveling from those countries, the White House has tried to allay domestic fears by ramping up protections in the United States.

Airline passengers already are being screened for symptoms of the illness as they board planes in those countries headed to the United States, during their flight here and upon their arrival in the United States at five designated airports that are the required entry points for travelers from those countries.

Now, those who arrive without exhibiting any sign of the illness will be followed for 21 days — Ebola’s incubation period — in the event they develop the virus.

The burden of monitoring will fall to state and local health officials, who have legal authority to control infectious disease, Frieden said.

“Fundamentally, this is an issue for state and local health departments,” he said. “They have procedures to identify people, track them and follow them up.”

Those health departments can choose to monitor people with daily visits, through electronic media like Skype or by contact with health programs where they work.

“What a logistical nightmare,” said John Connor, an associate professor of microbiology at Boston University and an investigator with the university’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories. “It is an abundance of caution, and certainly, if carried out properly, it would do a good job of identifying anyone who is infected. This is going to be a very difficult task.”

The number of people arriving in the United States from the Ebola-stricken countries has dwindled from an average of 150 a day to roughly 80 a day in recent weeks, most likely because U.S. residents have postponed trips to see relatives there for fear of the illness. Still, that translates into thousands of people for local authorities to screen and follow in coming months.

“We knew this decision was in the works, so we have begun our planning,” said David Trump, chief deputy commissioner for public health and preparedness for the Virginia Department of Health, who said local departments will play a central role.

Trump pointed out that if 20 passengers a day from the three countries arriving at Washington Dulles International Airport are subject to monitoring, the state could be following hundreds of people during any 21-day period.

“We’re still hammering out the details on this,” said Christopher Garrett, a spokesman for the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

The CDC guidelines require arriving passengers to provide detailed information on where they plan to be for the following 21 days, including their addresses, email contacts and telephone numbers for themselves as well as for a relative or friend in the United States.

That information will be forwarded to officials in the six states that will start the program next week. Four of those states — New York, New Jersey, Georgia and Virginia — are home to international gateway airports where travelers from the affected countries are required to enter the United States.

Frieden said that most people who arrive from the three African countries are U.S. citizens or long-term residents of the United States. He said about 70 percent of them live in or are visiting the six states where the monitoring program will debut Monday.

“State and local officials will maintain daily contact with all travelers from the affected countries for the entire 21 days following the last possible date of exposure to the Ebola virus,” Frieden said. “If a traveler doesn’t report in, the state or local public official will take immediate steps to find the person and make sure the tracking continues on a daily basis.”

The World Health Organization said Wednesday that at least 4,877 people out of 9,936 cases have died in the outbreak. There have been three cases in the United States: Thomas Eric Duncan, who fell ill four days after arriving from Liberia, and two nurses who treated him at a Dallas hospital. Duncan died Oct. 8.

The family of nurse Amber Vinson, who is being treated at Emory University Hospital, said Wednesday that the virus is no longer detectable in her system and that she continues to improve. The condition of nurse Nina Pham, who is being treated at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, was upgraded to good on Tuesday.

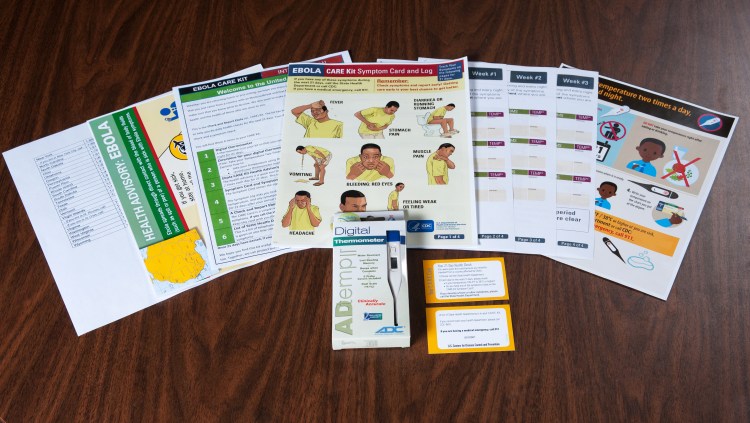

Starting Monday, each traveler from one of the impacted countries who arrives in the United States will be handed an Ebola care kit at the airport after being screened by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which is responsible for the enhanced airport screening. The kit includes instructions, a digital thermometer, a 21-day log sheet for recording morning and evening temperatures, a display card that shows the nine symptoms of the illness, and a list of telephone numbers for the CDC and state health departments.

Health-care workers — including those from the CDC — U.S. military and journalists returning from those countries also will face 21 days of monitoring.

Travelers with no known exposure to the illness while in West Africa will be permitted to travel within the United States provided they keep health officials informed of their whereabouts and maintain the 21-day health reporting. Those deemed high-risk, even though they have no symptoms, because of contact with an Ebola victim will not be allowed to travel on planes, trains or public buses. Those who ignore the no-travel edict could be prosecuted in some states under state laws intended to impede the spread of infectious diseases.

Frieden said the monitoring effort will allow authorities to react quickly if a person shows any signs of the illness.

“The strongest health measure we can take to protect each of us is to quickly isolate someone with symptoms of Ebola,” he said.

Local health officials would develop contingency plans to transport those with symptoms to a medical facility, he said.

“There is a possibility that other individuals with Ebola will come to this country,” Frieden said. “We’re undertaking a series of measures to increase the likelihood that if individuals arrive here and develop Ebola, they’ll be rapidly identified and isolated and will not spread Ebola.”

The pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson said Wednesday that in January, it plans to begin testing a vaccine combination that could protect people from one strain of Ebola.

The company described the vaccine as potentially effective against a strain “highly similar” to the one causing the epidemic. There are no proven vaccines or drugs for Ebola, and the New Jersey-based company is one of several racing to develop an effective means of defeating it.

Working with a Danish company called Bavarian Nordic, Johnson & Johnson said it will spend up to $200 million to speed the program. It involves two vaccines given two months apart.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story