If asked to list the most widely planted red wine grapes in the world, how many names would you come up with before you thought of grenache? For me there would be a lot. And yet it’s in the top five. Grenache thrives in hot, arid climates, from Spain and southern France to Sonoma, Australia and Morocco. In Sardinia, Italy, a “blue zone” of health and longevity, the natives ascribe their vigor and wellness to the wine from the local cannonau grape, which is grenache.

And, increasingly, so on. Once global climate change has smacked us around a bit more, maybe we’ll start drinking grenache from Germany and northern Italy too (and riesling and nebbiolo from Maine?).

Grenache is a hearty, thick-skinned grape. It yields copious amounts of fruit per bunch, can grow in a variety of soils, and can hang on a vine seemingly forever, gaining sugar (and therefore, later, alcohol) all the while. These more-is-better traits are liabilities once we get to the wine glass. High yields put less componentry into each grape, diluting flavor and aroma. Inattentive mating of grape to soil type leads to unfocused wines. Long hang times set fruit off balance, the grapes’ natural sugars concentrating and crowding out their natural acidity, so that all your exercised tongue can sense is overcooked fruit.

These are some of the reasons grenache is so often blended with other grapes, which can offer more structure, acidity and richness.

The most famous grenache blends are in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, where that grape is combined with up to a dozen other permitted varietals but usually plays a lead role. Côtes-du-Rhône, nearby, is made with either grenache or syrah in the majority, buffered by any number (including zero) of those helper varietals. Australia widened the popularity of the “GSM”: a combination of grenache, syrah and mourvèdre. In Rioja, garnacha plays best in a minor role if at all, content just to support the tempranillo and graciano.

These friends of grenache help it make sense, where alone it can be confusing.

Yet single-varietal grenache can sometimes come together, and its unique charms are worth seeking out. You’ll need a machete to cut through the thick bamboo forests of (sometimes quite expensive) mediocrity, but once you make it to the clearing there will be a very special party underway. The purity of crisp red fruit (bing cherry, gala apple, dark purple grapes) mingles with the character of violets, white pepper and fresh, loamy soil.

With grenache, less is almost always more. Less volume, less disbursement of flavor compounds, less time. Good producers severely limit their yields, and harvest on the early side.

Having older, less productive vines helps too, as does planting in terrain with poor nutrient value and excellent drainage: the big stones of Châteauneuf-du-Pape are the gold standard, but sandy soils work well too.

Seriously susceptible to the taste and texture alterations of oak, grenache is happiest when vinified only in used barrels, and not excessively.

These factors and more, when directed intelligently, yield wines where focus and even humility shine through. (I’ve tasted so many grenache wines where the overwhelming feeling is of having nowhere to hide.) It’s grenache, so even the humble ones have a lot going on. But it’s all of a piece rather than all over the place.

All grenache makes noise. When the noise is right, it’s like at a concert where the band is just getting into their groove. The crowd is jumpy, slightly rowdy, ready to dance or maybe get into a friendly tussle. Bad grenache is when the mics get turned up too high, and the feedback pierces your ears. Good grenache is when the sound mix is right and all those shoulders and heads between you and the stage start to bounce in unison.

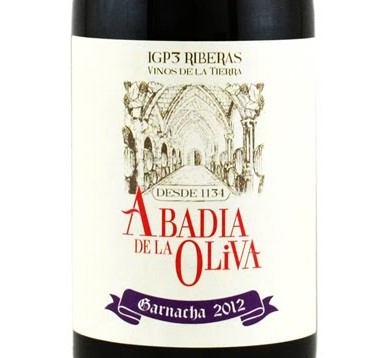

Abadía de la Oliva Garnacha 2012 ($13). The abbey in this wine’s name was established in the 12th century, when the King of Navarra set aside land to re-establish a Cistercian monastery along the river Aragon. The monks were farmers from the beginning, and were indeed obligated to drink two liters daily of the wine they made. It is the oldest continuously operating winery in Spain, with old vines in sandy and granitic soils and a tradition of simple, honest, undoctored wines.

The two-liters-a-day stuff was probably different wine from this garnacha, but the freshness and vigor in this timeless expression, fermented without oak primarily in cement tanks, are extraordinary. It is just a joy to drink such simple, lovely, seamless wine, medium-bodied, tuneful, aromatic and full of life.

Don’t drink the André Brunel VdP Grenache 2012 ($9) and then go thinking there’s a lot of under-$10 Provençal grenache that’s worth your while. This will spoil you for wines that cost twice as much.

Brunel’s importer, Robert Kacher, told me once, “When you stand in Brunel’s cellar and taste his VdP (Vin de Pays) grenache and his Châteauneuf-du-Pape, you really think, ‘Do I see a $50 difference?’ There’s a big difference in complexity, but great growers are going to make great wine at all levels.”

This is a great cheap wine. The grapes are almost all destemmed to yield softer texture, then gently pressed to avoid overextraction. The wine is bottled unfiltered, pushing a maximum of cooling flavors – blueberries in addition to cherries, herbaceous flowers – and dusty, grippy, undulating textures.

From the silkily simple to the rustically rich is a comprehensible journey. The trip from either of those wines, however, to the Hobo Sceales Vineyard Grenache 2012 ($22), is from the material plane to the astral. This wine bends my relationship to the time-space continuum every time I drink it, and I drink it often. And I need to stop, because only 10 cases of this small-production wine came into Maine, and now only four remain, and I want you to try it. (And I don’t know how or why, but the wine lists for $30 back home in California but only two-thirds of that here.)

I have written before about Kenny Likitprakong’s continually breathtaking wines. A self-described “hobo winemaker” who traipses from one California vineyard to the next just long enough to extract the most majesty each is capable of, Likitprakong has with this grenache dramatically raised his already high bar.

The Sceales vineyard has old vines and sandy soils, perfect for grenache. You get plums, spices by the dozen, thyme, meat broth, the most tantalizing perfumes, and the uniquely rounded, well-worn brawn that only grenache can offer.

Like a ballad by Likitprakong’s idol Woody Guthrie, it is simultaneously forthright and subtle, and helps you feel a calm at the heart of grenache’s perplexing storm.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. He can be reached at:

soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story