This is the first of three articles about the work experiences of Maine’s gubernatorial candidates.

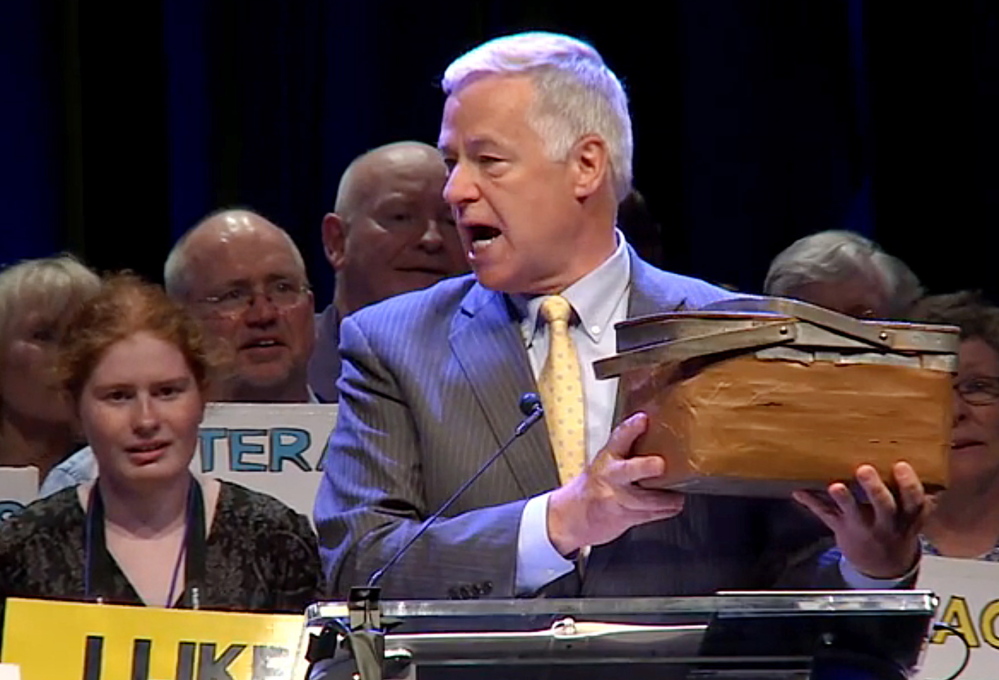

As he delivered a speech at the Democratic State Convention in Bangor last spring, U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud, the party’s nominee for governor, held up the lunch bucket that he used to carry his bologna sandwiches, apples and legislative papers to work at the Great Northern Paper Co. mill in East Millinocket.

“For 12 years, this lunch bucket has been sitting prominently in front of my desk in Washington, D.C., as a constant reminder never to forget to (keep) working for the hardworking men and women in the state of Maine,” Michaud told the assembled delegates. “Come next January, this lunch bucket will have a new home in Augusta.”

The lunch bucket – which resembles a small picnic basket – is more than just a prop for TV news clips or campaign ads. It’s a concrete example of how Michaud’s political identity is closely tied to his past experiences as a millworker for nearly three decades.

When he first ran for Congress in 2002, his campaign asked supporters to “fill Mike’s lunch bucket” with donations, and his television ads showed him wearing a hardhat, punching a time clock and working in the mill. By July of that year, supporters fed a little more than $400,000 into his lunch bucket. As of July 15 of this year, supporters had contributed just under $2 million.

Michaud has maintained that identity in Washington, D.C., where his leadership political action committee, which raises and doles out money to other Democratic congressional campaigns, is called “Mill to the Hill.”

It was in his early years in the mill when Michaud became an active leader in Local 152 of the United Paperworkers International Union, making him an ideal legislative candidate for the Democratic Party, which has long enjoyed the support of labor unions. He has consistently embraced issues important to the labor movement, such as increasing the minimum wage, protecting Social Security, increasing access to health care and opposing free trade agreements that imperil U.S. workers.

Michaud said his starting salary at the mill in 1973 was $2.50 an hour, which equates to $13.41 an hour in today’s dollars. That was 70 cents more than Maine’s minimum wage ($9.66 in today’s dollars) and 90 cents more than the federal minimum wage ($8.59 in today’s dollars).

Working on the banks of the Penobscot River, Michaud also saw firsthand how the mill created pollution by pumping sludge, a toxic byproduct of the papermaking process, into the river, and the 25-year-old ran on a platform of cleaning it up. His stances, contacts and interest in union activities and politics introduced him to influential Maine Democrats such as John Martin, the powerful House speaker, and former Attorney General James Tierney.

“It’s been a good career, and I wouldn’t be where I am today had I changed where I went to work when I first got out of high school,” Michaud, 59, said. “I wanted to clean up the river, but I also knew the mill provided a good lifestyle for the folks in the Katahdin region, so you did have to have that balance between environment, jobs and the economy, and that’s why I decided to run for the Maine Legislature.”

Michaud continues to enjoy broad union support and frequently notes that he is still a card-carrying member of the United Steelworkers, a union comprising 1.2 million members and retirees in the U.S., Canada and the Caribbean.

Michaud was honored as a “Working Class Hero” by the Maine AFL-CIO in June and the Southern Maine Labor Council on Labor Day. Speaking in August at the United Steelworkers of America’s annual conference in Las Vegas, he noted the importance of organized labor in his political victories, calling on labor to “once again roar” this Election Day.

This year the East Millinocket resident is counting on his union background in the mill – where his interest in politics earned him the nickname “the Governor” – to turn out middle-class voters in his effort to unseat Republican Gov. Paul LePage, who has sought unsuccessfully to weaken unions with so-called right-to-work laws.

A poll conducted in June for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram by the University of New Hampshire’s Survey Center showed Michaud holding a slight lead over LePage, but within the margin of error. Independent Eliot Cutler was in a distant third place.

A FAMILY AFFAIR

At its peak, Great Northern Paper Co. operated 11 paper machines in Millinocket and six in East Millinocket, and provided above-average wages and benefits to its workers.

In 1973, manufacturing wages in the Millinockets were nearly twice as high as the average for the rest of the state: $11,951 (or about $64,000 in today’s dollars) versus $7,050 (or $38,000), according to the now-defunct Census of Maine Manufacturers.

In 1980, the company employed roughly 4,300 people and had a payroll of nearly $115 million, or roughly $332 million in today’s dollars.

Drawn by good pay and benefits, the 18-year-old Michaud, who once considered a career in law enforcement and never went to college, went to work in the company’s East Millinocket mill after graduating from Schenck High School in 1973. It was a path taken by his father, James Sr., who worked at the mill for 43 years; his grandfather Frank, who worked there 40 years; and all five siblings, including his sister Lynne, who worked at the mill at one time.

Michaud eventually drove a forklift and having his father as his mechanic made him extra cautious on the job.

“Dad actually worked in what they called ‘The Cage,’ where they actually worked on the fork trucks,” Michaud said. “That’s why I was very careful so I didn’t have to bring in my fork truck so Dad would have to fix it.”

Entry-level positions were typically those involving hard labor in the wood room or the grinding room. There, workers would use pickaroons, or large hooks, to drag logs into the grinding machine, which turned the logs into pulp.

Michaud said he worked for a few weeks in those rooms before getting a full-time position in the paper room. There, he started as the sixth hand and was responsible for picking up the paper fragments, called the broke, which were the scrap pieces of paper and cores left over after the paper was cut to size. The broke could be small enough to pick up by hand, or so big it required a fork truck.

He would also cut and load cores onto the machine for the paper to be wrapped around. Cores could range from tightly wound cardboard to steel, with diameters of only a few inches up to 75 inches, he said.

He worked his way up to the third hand, where he ran the paper winder, a large stationary machine run by computers.

Michaud said he worked those jobs full time until after he was elected to the Legislature in 1980. Shortly after taking office, he went to work in the finishing room, where he would wrap finished paper and load it onto rail cars and trucks for delivery using a fork truck.

“I did that for a while – and working midnights after spending all day in Augusta and then working all weekend,” Michaud said. “(It) started wearing on me, so I signed out to the finishing room.”

LABOR TIES

Michaud’s years working in the mill allowed him to become a labor union leader while staying abreast of the issues important to people living in the Mount Katahdin area.

Michaud said he was elected to serve as the vice president of Local 152 of the United Paperworkers International Union for “a couple years.”

“Mike was a good union man,” said Donald Hensbee Jr., a former board member of the pulp and sulfite union. “He fought for people’s rights to have good insurance and good jobs. And that’s why I think he got into that political scene.”

Since pay raises were already outlined in the contract, Michaud focused on expanding the scope of health care coverage and reforming the pension system to improve benefit plans for retirees, according to his campaign.

Michaud said he became active in the union largely because his uncle was a longtime union treasurer and secretary. Being a union leader as well as a shift worker helped give him an appreciation of the challenges workers faced.

“Having punched a time clock and working shift work, you really get to know what people have to go through day to day,” he said. “Being a union officer, you tend to hear complaints and concerns among other fellow workers as far as some of the struggles that they go through.”

In addition to being a former union officer, Michaud was vice president of the Maine Young Democrats and served as a committee member of a local credit union before he was elected to the Maine Legislature.

He was also a member of the Consumers Opposed to Inflation in Necessities, or COIN, a group formed by the AFL-CIO to fight the rising costs of food, housing, energy and health care. He was also a special organizer for the union in 1978.

Michaud said his friends, family and co-workers urged him to run for office. He also argued that wages were not the cause of inflation, which was high at the time.

Among those recruiting Michaud to run for office was then-House Speaker Martin, who was known to some as the “king of the St. John Valley” or the “ayatollah of Eagle Lake.”

Martin said Michaud’s history of working in the mill, his ties to labor and his desire to help others all made him a good candidate.

“(Michaud) ended up being interested in issues that I had an interest in – natural resources and labor, and those kinds of things,” said Martin, who noted that he frequently helped recruit candidates for the party. “He was a hard worker. If he needed to work at night to get the job done, he’d do it.”

Tierney, who worked as a union lawyer before becoming Maine attorney general in 1981, said Michaud was an “active and articulate labor leader.”

“No one was surprised and we were all pleased when he ran for and won a legislative seat that had been in GOP hands for years,” Tierney said in an email.

While Michaud has been described as Martin’s protege, both men downplayed that characterization, saying many Democratic lawmakers from northern Maine could be called that.

Michaud said Martin was instrumental in helping him learn parliamentary procedure in the House. In return for his interest, Martin would often appoint Michaud as speaker pro tempore.

When it came to his positions on the issues, however, Michaud said he always focused on his constituents.

“I’ve always been very independent in my votes. My focus has always been the constituents that I represented, not the party or any individual,” Michaud said.

‘THE GOVERNOR’

Michaud worked full time in the mill for seven years before being elected to the Legislature.

The union contract allowed him to take an unpaid leave of absence while the Legislature was in session. So Michaud would work nights and weekends, as his legislative calendar allowed.

“They called him ‘the governor’ every once in a while,” said Hensbee, the former union official. “He’d take a good ribbing. I think he got teased. He laughed all the time. He took it well.”

Chris Morin, a 57-year-old Democrat who is unemployed and worked with Michaud in the finishing room, said Michaud usually would carry around a notebook so he could write down anyone’s questions about legislative issues. He took pride in being able to respond to concerns, Morin said.

“I think he really delved into politics big time,” said Morin, who is supporting Michaud’s candidacy.

Michaud also sponsored a softball team for his mill co-workers, who would travel to Augusta and stay at a split-level ranch Michaud still owns with Martin. The team was called the State Reps., which allowed Morin to get to know Michaud.

Aside from being a legislator and millworker, Michaud said he co-owned a few apartment buildings with his brother. He also co-owned Moose Point Camps on Fish River Lake with Martin and Patricia Eltman, a former director of the Maine Office of Tourism.

Michaud said he was a partner in the business for about five years. Martin estimated Michaud invested $15,000 to $20,000 in the venture. Michaud divested himself of the business shortly before running for Congress.

During his years as a mill-working state legislator in the early 1980s, Michaud said few of his co-workers were concerned about taxes, since many people in the region were making good money at the mill. Instead, they were more concerned about education as well as fishery and wildlife issues, he said.

And apparently they could be passionate about the issues.

Jeff Marks, a 44-year-old Portland resident who is executive director of the Environmental & Energy Technology Council of Maine, recalls working overnight shifts with Michaud for two summers in the finishing room, when he came home from college. The two would discuss public policy during 3 a.m. coffee breaks, said Marks, whose father was the basketball coach at Schenck High School when Michaud was a statistician for the team.

“Even when they (his co-workers) were ripping him about Augusta politics, he kept his cool,” said Marks, who is not enrolled in a political party. “I could tell they respected him and he always reciprocated.”

Morin said Michaud never allowed himself to get into screaming matches about politics.

“I never saw anybody get into a heated argument with him. I don’t think Mike would let himself get into that situation,” Morin said. “He never said anything bad about anybody. That’s what impressed me about Mike for all of these years.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story