The three cast iron skillets, wrapped tightly in bubble wrap, sat on a stool in my dining room for months. I felt guilty every time I looked at them because I knew how much trouble my father had gone to in cleaning and re-seasoning them. And these weren’t just any skillets. They belonged to my great-great-grandmother, Rebecca Watson.

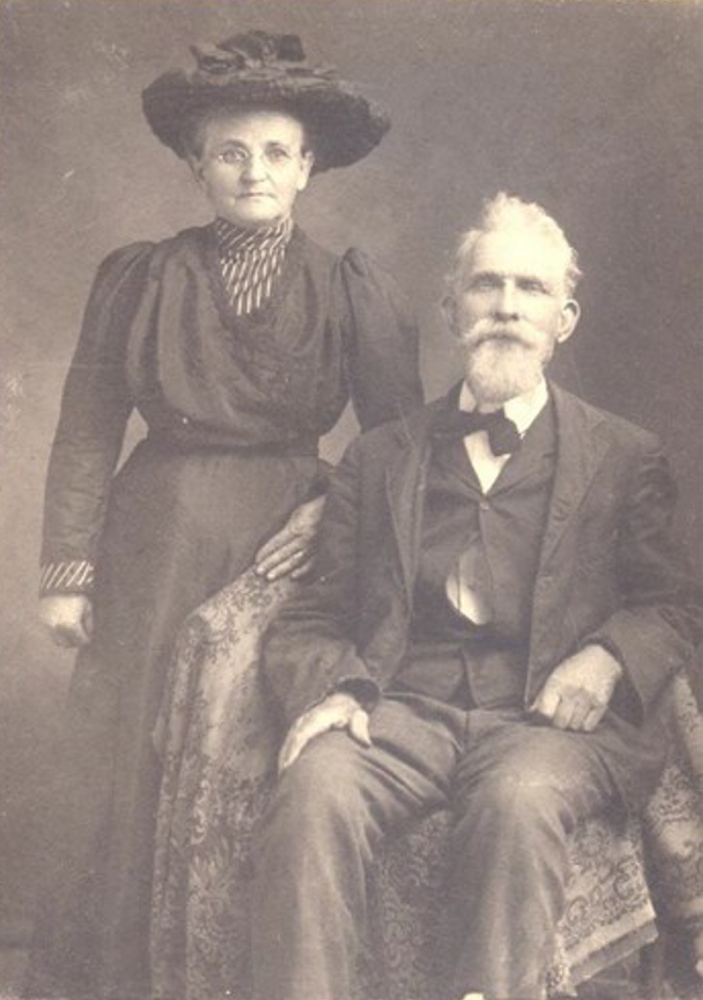

Rebecca Elizabeth Fitzgerald married Elijah Hanks Watson in 1871, when she was just 20 years old. At 32, her new husband was much older, but for good reason – he was a Civil War veteran who had fought with the Confederate cavalry at an age when otherwise most young men would have been settling down. They acquired the skillets shortly after they were married, or so the family story goes.

Last year when I visited my parents, my father was hard at work restoring them so I could bring them back to Maine. I was touched that he wanted to give them to me, and appreciative of all the hard work he was doing refurbishing them. But when everyone urged me to cook with them, I balked. As I listened to my father talk about cleaning a century’s worth of crud using various cleaning agents and plenty of elbow grease, I wondered, would any of that stuff leach into the food?

Another concern: I believed, for some reason, that my father had found the skillets under my grandmother’s house when he was cleaning it out. Nellie Goad, who was my grandmother and the granddaughter of Rebecca Watson, died in 2005 at the age of 103. My grandmother had already given me her butter churn, which had lain under her house for years. I wanted it because it brought back fond memories of my sister and me lumbering into her kitchen at 5:30 a.m. in our pajamas to make butter and biscuits from scratch while our grandfather was down in the barn milking his cow.

A butter churn I’ll never actually use is one thing, but the thought of using skillets that had been stored under the house for potentially decades was not exactly appetizing, no matter how well they had been cleaned.

And – yes, I realize this is silly – I was fearful that if I used the skillets, I might ruin or “break” them in some way because they are so old.

So I announced to my family that I would probably just hang them on my kitchen wall for display, and went off to research vintage cast iron skillets on the Internet.

If he was disappointed, my father didn’t show it. When I finally got around to unwrapping the skillets back in Maine, I found tucked in with one of them a handful of screws and bolts he had neatly wrapped in duct tape to make the job of hanging them a little easier.

Recently I decided to call him to find out more about the skillets. It turns out I was wrong; my grandmother, who had gone kicking and screaming into an assisted-living facility in her mid-90s, had been storing them in her stove, not under the house. She had asked my father to take them home for safekeeping.

“She said, ‘Somebody will come in and steal them, and I don’t want those to be lost,’ ” he recalled.

CHASING CLUES

Two of the cast iron skillets are about the same size and have distinct markings on them. (Cast iron skillets have changed remarkably little in the past 144 years, except for the markings that usually indicate who made them – and when.) The third is smaller and has no markings; my father suspects it belonged to my grandmother and got caught up in the “save the skillets” rescue mission.

The two larger skillets both have the number 7 etched on their handles. The number, I learned, refers to the size of the underside of the skillets, which were made to fit in the circular openings on the top of woodstoves – also known as stove eyes.

“With those pieces there’s usually a little bit of a raised rim on the bottom so it would stick inside that burner,” said Mark Kelly, a spokesman for Lodge in South Pittsburgh, Tenn., the only remaining manufacturer of cast iron cookware in the country. “You could put it in there and it wouldn’t move around.”

Also on the underside of the skillets are markings called gate marks – a long, raised, lumpy-looking line that reveals where the iron entered the mold.

I sent photos of my skillets to Sam Smith, the blacksmith who owns The Portland Forge on Fore Street, and he said he could tell by the gate marks that they were “definitely pre-1890.”

“It’s a process they stopped using by 1890 altogether, commercially,” he explained. “If you do some more research into the way the gate mark looks, you can actually identify it that way if there’s no maker’s mark.”

Gate marks sometimes changed depending on the process and the size of the equipment foundries were using to pour with, Smith said: “Some will be wider, some will be longer, some will have something on the side. You have a square spot on the side, it seems. That’s a gate mark as well.”

Smith said he could also tell that my skillets were made in the South because they have loops in the handles – a trademark of foundries in larger Southern cities such as Atlanta, Charleston, New Orleans or Chattanooga.

My skillets may have been made in a large city, but they ended up in hillbilly country.

FROM THE HILLS OF TENNESSEE

A colleague of mine likes to joke that I am “from the holler.” He’s only one generation off, actually.

My father and his family come from the hills of middle Tennessee, near the town of Columbia (pop. 35,000), known as the “mule capital of the world.” (In 1840, the year my great-great-grandfather was born, Columbia began a “Mule Day” celebration that continues to this day with a parade, a mule pull and other competitions.)

My grandparents’ 25-acre farm, inherited from Elijah and Rebecca Watson (or Pa and Ma Watson, as they are known to the family), was about a half-hour drive from Columbia in a place now called Haywood Hollow (named after another branch of my family) in the vicinity of Knob Creek. Hill people, many of them my relatives, lived deep in “the holler,” as my Vanderbilt University-educated father still calls it.

I don’t have any proof of this, of course, but I imagine those cast iron skillets were prized possessions when my great-great-grandparents got them back in the 1870s. Elijah, like most Civil War soldiers, came back from the war destitute. Why he fought in the first place is a mystery; he never owned a slave or lived on a plantation, and he was known in the family and by the community as someone who adhered to a strong moral code. What’s worse is he rode with Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, a man revered for his military tactics but also a reviled slave owner and slave trader.

“I know that my great-grandfather never owned a slave in his life,” my father says when asked about Elijah’s time fighting alongside Forrest. “But there have been a lot of instances of young men fighting for a cause they did not understand. That’s all I can say about that.”

When Elijah returned home from the war, he had no mule or horse or plow, so he planted his first crop by hand.

“He went out into an old corn field, where corn had been grown,” my father explained. “He went along and pulled up the corn stalks, would drop a seed of corn down into the hole, stomp on it with his foot to cover the seed and then went on to the next. And he worked that crop with a hoe. They didn’t have money to buy anything back in those days.”

That included soap and salt. They made their own soap at hog-killing time. When they needed salt, Elijah made it using a big cast iron kettle that was displayed in our home for many years (my father says my mother gave it away years ago, but she swears it is still in the attic somewhere).

“He went out and dug up dirt in an old smokehouse where they had salted-down meat, and that soil was saturated with salt,” my father said. “He dug up that dirt, put it in the kettle, filled the kettle with water, swished everything around until the salt was dissolved in the water, then let it set and let the dirt settle to the bottom. He would pour the liquid off the top into another container, wash the kettle out, put the liquid that he’d poured off back in the kettle, build a fire under it, evaporate the water and then get the salt off of the bottom.”

Whenever I find myself worrying how I’m going to pay my bills and feeling sorry for myself, I think of Pa Watson.

SCANDAL IN THE FAMILY

Elijah Watson eventually bought a mule, and then a plow. He saved up enough to buy a little plot of land here and there, and before he knew it, he had 175 acres.

“Every dime he got his hands on he saved,” my father said. “He never spent any money at all if he could possibly avoid it. And he was a well-respected person in the community. Anybody that had 175 acres, that was a pretty good-sized farm for Knob Creek.”

Rebecca died of influenza-induced pneumonia at the age of 74, a year and a half before my father was born. My father, who will be 87 next month, says he probably heard about her cooking at some point growing up, but he doesn’t remember any details. He does recall how much my grandmother worshipped her.

It’s likely Rebecca’s daughter, my great-grandmother, used the cast iron skillets next, and they soon were embroiled in a family scandal.

Elijah and his bride were blessed with two children, a son and a daughter. Who knows why two such loved and respected people ended up with such troubled children, but that’s what happened to Ma and Pa Watson.

Rebecca’s daughter was always the black sheep of our family. My siblings and I remember her as a nice old lady we would go visit once in a while, and she would give us Juicy Fruit gum. We called her Ma, but her name was Rosa, or Rosie. My father called her Grandma Rosie. There were always whispers about her past, but whenever I’d ask my dad he would say he’d tell me when I was older.

Maybe it’s because I’m a reporter, but I have never been able to abide family secrets. Over the years, the bits and pieces of stories I heard about Rosie began to really frustrate me, and I started pressing my father for a more complete picture of this woman who was sometimes described as mean, but very intelligent.

Rosie married Walter Haywood (Haywood Hollow, remember?) on Sept. 16, 1900, when she was just 15 and he was 17. Two years later my grandmother Nellie was born, and by 1920 Rosie had eight children. On the 1920 census they are all stacked together along Knob Creek Road – my grandparents, great-grandparents, great-great grandparents … and another family whose name I shall leave out here because after Walter died of a heart attack in 1923, Rosie took up with the (married) head of this other household. Her new boyfriend was also, apparently, the black sheep of a respected local family. This clandestine affair was supposed to be secret, but everyone knew about it.

Rosie lived in a log house with some of her children and (by 1926) her widowed father, Pa Watson, who owned the house and the land it sat on. Instead of using her mother’s cast iron skillets to feed her family, Rosie would make elaborate meals for her lover and then disappear with him for long periods of time. They spent a lot of time making moonshine together, tending a still they hid way back in the hills. For all of this unseemly behavior, Rosie was kicked out of Knob Creek Baptist Church, along with one of her sons, who had helped cover up the affair.

After a while, Elijah couldn’t take the family shame anymore.

“Pa Watson showed up in our yard one night,” my father said, “and mother and daddy went out on the front porch to talk to him and see what he wanted, and he asked my dad if he could come down there and live with us, that he didn’t approve of his daughter’s lifestyle and he just couldn’t live with her any longer.”

Over the years I have defended Rosie as a free spirit trapped by convention and the times she lived in, even though I know she hurt a lot of people. I grew up during the women’s movement of the 1970s, and as I heard the stories about her I began to admire the very things her own community considered scandalous – Rosie’s rebellion against authority, and her desire to live life on her own terms. (How can you not admire someone who has a torrid affair after giving birth to eight children? Most women would be too exhausted.)

My father’s attitude towards his grandmother has shifted over the years as well. He now says Rosie was “born a couple of generations before her time. She was unconventional.”

Researching the skillets and talking about family with my father made me go back to the records and I discovered that, in the 1930 census, Rosie was not only living with her paramour, they were listed as husband and wife. Whether they actually married, or were just putting on a polite face for the census taker, I don’t yet know.

Pa Watson eventually hired a lawyer in Columbia and split his property up so he could leave most of it to his grandchildren. (His only son, William, whom I mentioned earlier, was a farmer who longed to be a teacher and was trapped in a bad marriage. He “lost it” one night and was committed to the Tennessee Hospital for the Insane in Nashville. But that’s another story for another time.)

Elijah died in 1931 at the age of 91. My grandmother inherited his best plot of land, 25 acres of mostly cultivatable farmland. Rosie got eight acres and the log house she lived in, and she resented the snub from her father for the rest of her life.

FRIED GREEN TOMATOES

Eventually the cast iron skillets ended up in my grandmother’s kitchen. I watched her make my father’s favorite breakfast in them whenever we came to visit – thick slices of country ham with red-eye gravy. Maybe she would crack an egg or two from her chickens as well.

My father’s favorite skillet memory is watching his older sister make fried green tomatoes, which to this day he gobbles down like a seal eats fish. “I stood there by the stove with a plate and a fork,” he recalled, laughing. “Every time she’d pick some out and flop them on the plate, they would suddenly disappear down my gullet. It would make her so mad.”

My own cast iron memories also include a different set of skillets – my mother’s. She always made her fried chicken in cast iron, and there is nothing better than skillet cornbread, or pancakes made right after a batch of bacon.

I’ve been researching my family’s history for years, but my great-great-grandmother’s skillets have made me think differently about some of the stories I’ve heard. They have filled in some gaps for me, and given me new leads to follow.

So maybe, in honor of Rebecca and Rosie and Nellie and my mother, I should set my worries aside this weekend and fry up some bacon, and maybe follow that with a pan of skillet cornbread.

I’ll cook with them knowing that I am only their temporary caretaker. Some day, I’ll pass along the skillets – and the stories – to one of my nieces, and it’ll be her turn to ensure that the memory of these strong women lives on.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story