PIERRE, S.D. — Laura Ingalls Wilder penned one of the most beloved children’s series of the 20th century, but her forthcoming autobiography will show devoted “Little House on the Prairie” fans a more realistic, grittier view of frontier living.

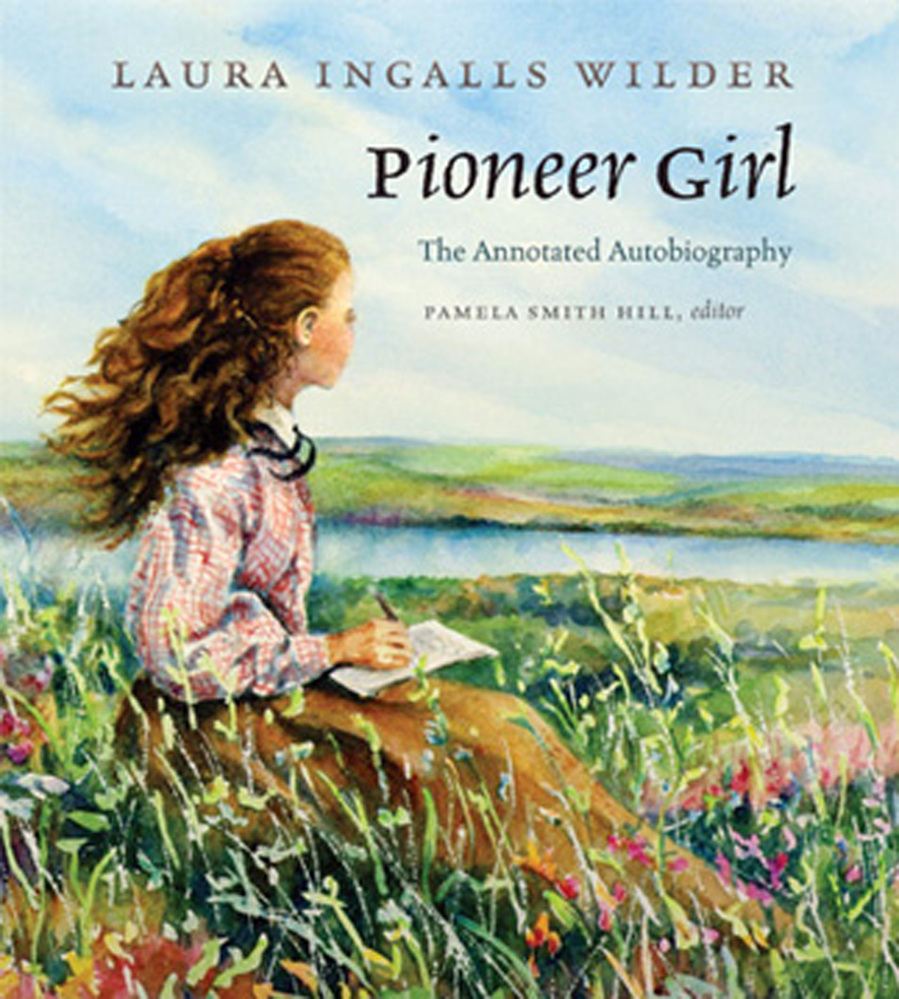

“Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography” – Wilder’s unedited draft that was written for an adult audience and eventually served as the foundation for the popular series – is slated to be released by the South Dakota State Historical Society Press nationwide this fall. The not-safe-for-children tales include stark scenes of domestic abuse, love triangles gone awry and a man who lit himself on fire while drunk off whiskey.

Wilder and her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, herself a well-known author, tried and failed to get an edited version of the autobiography published throughout the early 1930s. The original rough draft has been preserved at the Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Home and Museum in Mansfield, Missouri, for decades but hadn’t been published.

The children’s series never presented a romanticized version of life on the prairie – in “Little House in the Big Woods,” Laura and her sister, Mary, gleefully help dissect the family pig before bouncing its inflated bladder back and forth in the yard. But the series also left out or fictionalized scenes that Wilder deemed unsuitable for kids, including much of the time the family spent in Burr Oak, Iowa, and Walnut Grove, Minnesota, according to Pamela Smith Hill, a Wilder biographer and the lead editor on the autobiography.

“So you can read `Pioneer Girl’ as nonfiction rather than fiction and get a better feeling of how the historical Ingalls family really lived, what their relationships were and how they experienced the American West,” she said.

Wilder details a scene from her childhood in Burr Oak, in which a neighbor of the Ingalls’ pours kerosene throughout his bedroom, sets it on fire and proceeds to drunkenly drag his wife around by her hair before Wilder’s father – Pa in the children’s books – intervenes.

Scenes like that make Wilder’s memoir sound like it’s filled with scandal and mature themes, “which isn’t exactly true either,” according to Amy Lauters, an associate professor of mass media at Minnesota State University-Mankato.

“It’s just that that first version was blunt, it was honest. It was full of the everyday sorts of things that we don’t care to think about when we think about history,” said Lauters, who has read the original manuscript and also is writing a book on Rose Wilder Lane. “And it’s certainly not the fantasized version we saw on `Little House on the Prairie’ the television show.”

Wilder’s story will likely do well in South Dakota, since the author moved to De Smet in the late 1870s with her family, eventually meeting her future husband there.

For fans, the autobiography is chance to see from where Wilder drew her inspiration, said Sandra Hume, a Wilder aficionado who published an internationally distributed newsletter for 10 years and now helps manage Laurapalooza, a conference dedicated to all things Wilder.

“I am very excited to see people have access to this, because her life story has been pretty muddled because people get mixed up with the TV show and it’s nice to see an interest in people seeing basically what is the primary source …” she said.

The autobiography preserves Wilder’s original rough draft – misspellings, idiosyncrasies and all – but adds extensive annotations.

“Little House” lovers can learn about the three girls that Wilder combined to create the Nellie Olson character, or how extensive the damage was in Minnesota during the grasshopper plague of the 1870s, which forced Pa in “On the Banks of Plum Creek” to set out in search of work.

“In some ways, I came to think of the annotations in `Pioneer Girl’ as almost an encyclopedia about Laura Ingalls Wilder’s life and work,” Hill said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story