There are those who approach a given wine the way mid-20th-century New Critics did literary works. They strip their analysis of all cultural and historical references and any sort of romantic, obviously subjective sympathies, to arrive at a more putatively objective focus on the thing itself. This approach favors a strict internal examination of how a wine works, how its structural components (flavor, aroma, body, etc.) collaborate.

To encounter a skilled practitioner of this orientation is thrilling, but there are so many failed attempts, so many depressingly obtuse imitations that, especially in recent years, a counter-movement has formed. We could call this counter-movement the New Subjectivism: mostly younger, more emotive writers and sommeliers whose aim is less to explain than to exult. For these folks, “the story” behind a wine is integral to its enjoyment.

This story is often about politics and ecology, and it involves a David/Goliath theme favoring the handmade over the mechanical, the unfamiliar over the known, the little guy over the big. I have told these stories many times before, because I like learning about them, and I can tell that other people like hearing them.

But the elision of a wine’s story and its character, this assumption that because what goes on in the vineyards or at the winery is emotionally attractive it is also therefore significant, makes me increasingly anxious. I no longer feel entirely satisfied with the assumption that background matters.

This unease grew dramatically over the past week, as I tasted wines with one of the best wine stories ever. These are the California wines of Grgich Hills Estate, whose co-founder, Miljenko “Mike” Grgich, created the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay that beat France at the (in)famous Paris Tasting of 1976.

I tasted Grgich Hills wines for the first time two years ago, fell hard for them and have been preparing since then to return to them and interview this living legend. I wanted to talk with the man, a Croatian immigrant to the United States, who truly did start an international wine revolution.

Before the “Judgment of Paris,” the French were undisputed champions. After that event, the American wine industry vaulted to the fore. There is a general impression now among wine enthusiasts that a great wine can come from any number of places on the planet.

That’s just the most obvious headline of the Grgich story. You can read about the 1976 Paris tasting online, in magazine articles and more than one quite good book. You can see films based on it, too. You can debate endlessly whether the criteria in 1976 were fair, or you can thrill to the image of Ronald Reagan packing a few cases of a later Grgich vintage on board Air Force One, to serve to François Mitterrand at the American Embassy in Paris.

I was planning to interview Mike Grgich for the article I’m writing now, to hear his tales firsthand and communicate them to you. I was also interested in his relationship with his nephew, Ivo Jeramaz, another Croatian, who is the Grgich Hills vineyard manager. But I drank the wines and all went soft and soundless around me. The story matters, but not quite at the moment you’re drinking, which suggests that the most mesmerizing stories Mike Grgich has to tell might not use words.

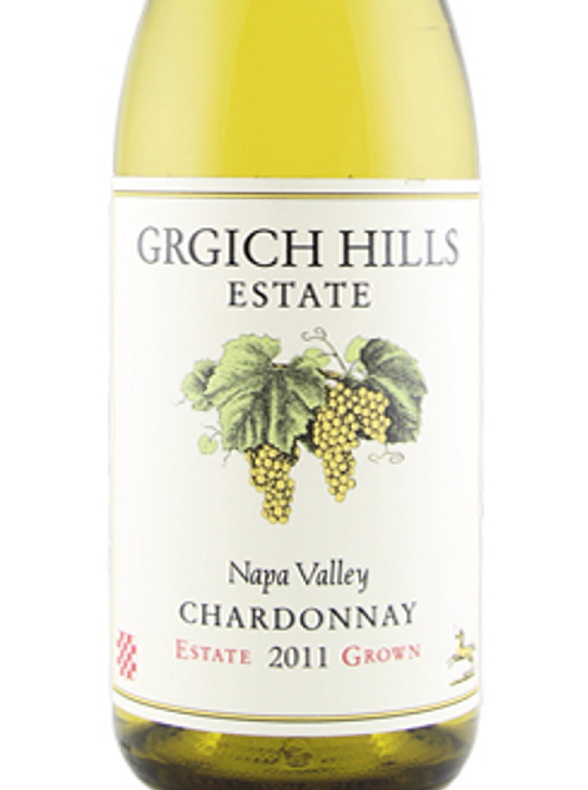

Let’s start with the Grgich Hills Estate Chardonnay 2011 ($42). Unless you’re far luckier than most of us, you have no idea whether it tastes similar to the 1973 Chateau Montelena. But it is so clearly, cleanly excellent; so elegant, forthcoming and refreshing; so long-lived, so simultaneously sumptuous and pristine. It brings you deep into the heart of a grape whose heart is frequently hidden.

The Grgich wine, from biodynamically farmed organic grapes grown in the Grgich Hills Napa vineyards and fermented only with indigenous yeast, is in an ideal state of balance. Though 2011 was a relatively cool vintage, the wine did not undergo malolactic fermentation, and so a tremendous tangy freshness is preserved. This tanginess shines through despite oak treatment (fermenting and aging in a mix of new and used French oak for 10 months) that might cause a cynic to reject it out of hand.

Let the anti-oak theoreticians tell their stories, and let those who think they have “moved on” from Napa Chardonnay tell theirs. This is, simply and confidently, a classic wine. The balance is not one where different components pull on each other so that nothing falls over. Instead, it’s one where there exists an underlying network of entire lives – lives of acid, lives of fruit, lives of earth, lives of herbs, lives of rocks – like the fungal substructure beneath a forest.

Even at flat-out room temperature in August, having been opened several nights previously, it was revitalizing, alive. This is something that only very special wines do. They belie the notion that special circumstances, special foods, special anything, are required. You could drink the Grgich Hills Chardonnay with something expansive and rich, like lobster or grilled pork, or you could do a simple omelet and some cream-smashed potatoes strafed with cider vinegar, or chicken tacos. Still, you will be transported.

The Grgich Hills Estate Cabernet Sauvignon 2011 ($60) will, like the Chardonnay, disabuse you of many a preconception concerning wine from Napa Valley. It comes on like the plums fresh from the icebox in that great William Carlos Williams poem – “delicious/ so sweet/ and so cold” – and from there brings licorice, eucalyptus, green peppercorn, an almost Zinfandel-like spice, anchovy, shiitake broth, fresh damp tobacco.

The coolness of the wine, the bracing mineral stance, and the granularity and dusty black rigor suggest an earlier generation of Napa Cabs, when the alcohol was often below 13 percent (the Grgich is, in this warmer era, a respectable 14.2 percent, though it tastes like substantially less) and the aim was sensitivity rather than power.

Indeed, to veer briefly into the story, look at the shape of the bottle, an homage to Napa Cabs from the 1980s and earlier. Those sloping shoulders are emblematic of a young California wine culture that was both bold enough to go for everything (prizes and class and magnificence) and humble enough to produce wines that listened well, and spoke softly.

Those were the wines that seemed to say, even as they aspired to take the world by storm, “We stand on the shoulders of giants.” The past 30 years have seen majority rule by wines that rarely acknowledged such a debt. The story itself, indeed, is usually told immodestly, with a tone of high American triumphalism. But the wines themselves, well, they talk low. So that you can better hear their thrilling sagas.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. He can be reached at:

soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story