Loons, along with moose, are icons of the wilds of Maine. So a picture of loons on a lake surrounded by mesas and canyons, or off a desert coast, came as a shock. And it was a surprise to learn that, of all common loons, only 6 percent are American – that is to say born in the USA.

At least we can take pride in the fact that male Maine loons, at an average of 13 pounds, are some 40 percent bigger than most, the consequence of a shorter journey when they migrate, a mere 100 miles to the Gulf of Maine as opposed to the 2,000 miles between Manitoba and Baja California.

These are but the tip of the iceberg of fascinating facts about loons to be found in a delightful book by a couple who have made the study of the Gaviidae family their life work. David Evers and Kate Taylor work for Biodiversity Research Institute, which Evers founded, and they have studied loons all over the country.

You don’t have to be a wildlife biologist to be mesmerized by loons. They are haunting creatures from a primeval world, which is why they are the first species described in taxonomically organized bird books.

“Journey with the Loon” considers the life history of Gavia immer in four seasons. It starts when early spring prompts the birds to return to their breeding grounds, the northern lakes that are opening with the spring thaw.

“For loons, fidelity lies with their territory, not with their mate,” the authors tell us. Evidently when the same pair from last year shows up on the same lake, they form a bond, though rarely “for more than seven years.” The book comes full circle as the “long silence of winter descends” once more and the birds fly south.

It’s a poetic framework, and the authors make the most of it. In fact, as I read the essay that introduces each chapter, I felt I was listening to the gentle commentary of an old nature film. These biologists have a charming writing style, only occasionally jarred by more scientific lingo. “Growing new feathers,” they write, “requires an energetic investment.” Meaning it takes a lot of calories, not overtime with a financial adviser.

To do equal justice to loon biology, each essay is followed by well presented, more technical information, such as the flyways of different populations displayed on annotated maps, how the birds adapt to aquatic life (and seasonally re-adapt to salt and fresh water), and, of course, the language of loons. No one who has heard several pairs “night chorusing” on a large lake will ever forget it.

The book’s first sentence may blindside some readers: “We set out in a canoe to capture loons.” All is explained mid-volume under the heading “To Band a Loon,” which describes this basic tool of their research.

Here I wished Evers had been less modest about how he “discovered a reliable and replicable method of capturing loons.” No one had ever succeeded in catching live loons before, so this was a big advance for loon research. (In the interests of full disclosure, I was once on the board of the Biodiversity Research Institute.)

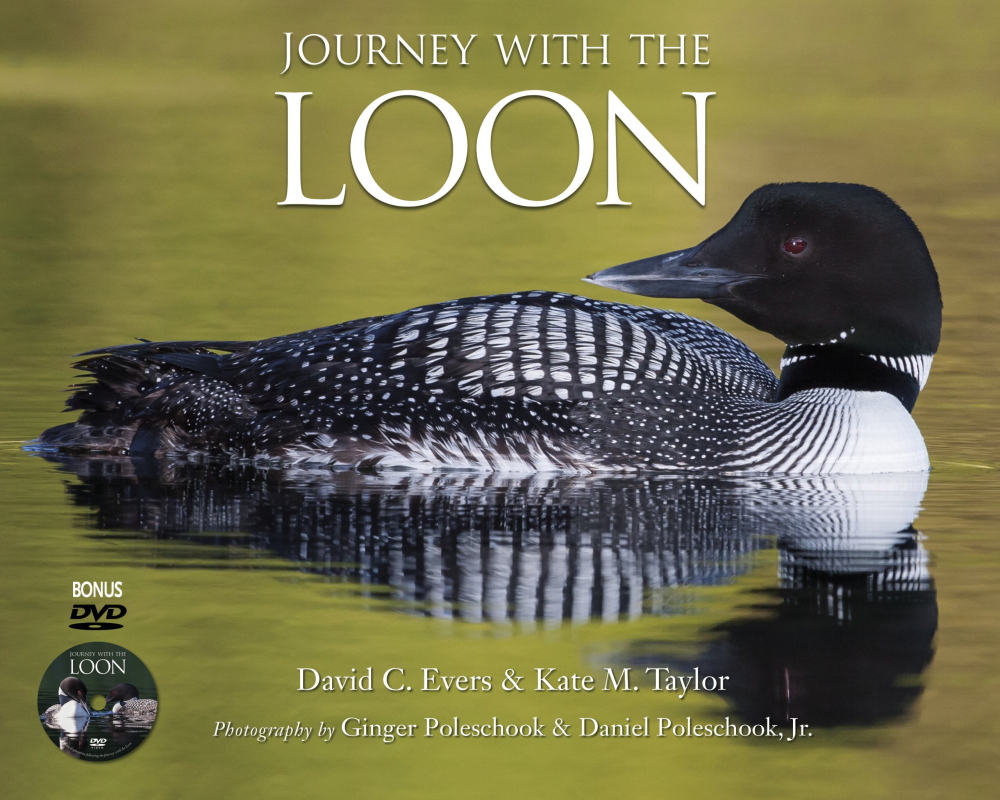

To balance the informative text, “Journey with the Loon” includes page upon page of photographs.

Loons are inherently photogenic, and these are some of the most evocative photographs I’ve seen. The photographers – another couple, Ginger and Daniel Poleschook Jr. – give us loons in every sort of situation, activity and plumage.

One sequence tracks the week by week development of a newly hatched chick over more than three months; in week 3 it waves an outsize webbed foot: the limb’s growth is “rapid and disproportionate,” providing for extra mobility that is much needed in a pond full of snapping turtles.

“Journey with the Loon” is handsomely produced and includes a 15-minute DVD showing loons in all seasons.

There are aspects of loon behavior (any behavior, for that matter) that elude even the best still photograph. Interactions between adult and chick are an example. And then, of course, you also get the legendary wild calls and yodels on a recording.

As I watched the DVD, I couldn’t help reflecting (and regretting) that the heart-warming narration of the old nature film had been replaced by stock muzak of a fairly meretricious kind. But then I remembered that I had already “heard” it in Evers’ and Taylor’s lovely text. It’s a beautiful book.

Thomas Urquhart is a former director of Maine Audubon and the author of “For the Beauty of the Earth.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story