Maine’s hospitals used physical restraints and seclusion techniques on psychiatric patients last year at higher rates than the national average, according to new data released by the federal government.

The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services encourage hospitals to minimize such practices. Hospitals have had to report rates for years, but the numbers have not been made public until this spring.

Restraints are counterproductive for the well-being of people with mental illness, experts say, and are not as effective as other techniques to control patients’ behavior.

Not using restraints is “the safer way and the more orderly way, but not the easy way” to treat patients, said Jenna Mehnert, executive director of the Maine chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Mehnert said restraints encompass various methods, including using safety vests and jackets, strapping someone to a chair, putting mittens on a patient, holding a patient on the floor, or using drugs that have no therapeutic value but calm patients.

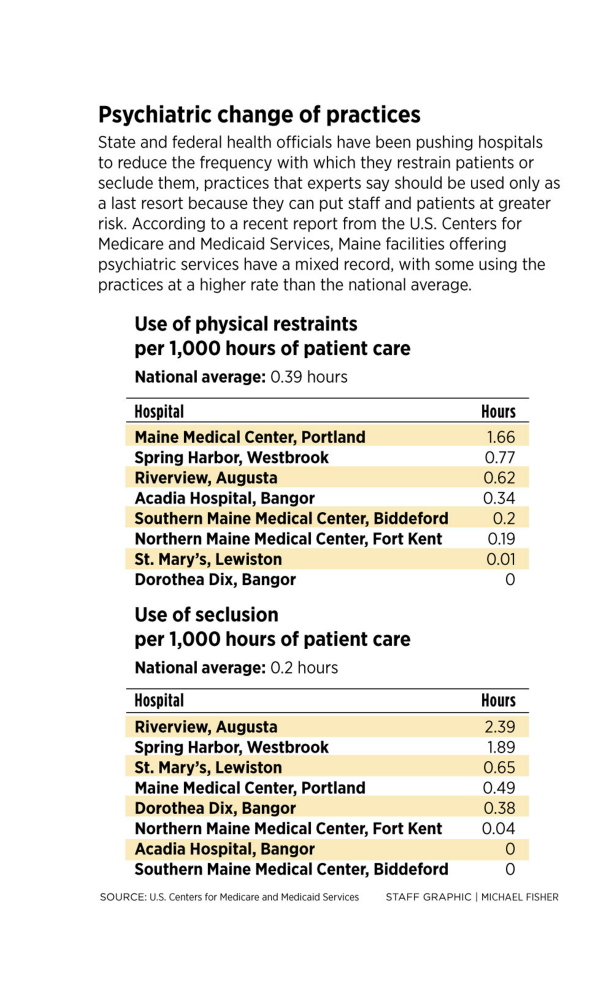

Maine hospitals reported widely differing rates of restraint and seclusion in the six-month period from October 2012 through March 2013.

The national average for restraints was 0.39 hours per 1,000 hours of patient care. For seclusion, the average rate was 0.2 hours. Maine facilities averaged 0.48 hours for restraints and 1.15 hours for seclusion techniques.

In Portland, Maine Medical Center’s rates were higher than the national averages in both measures: 1.66 hours for restraints and 0.49 hours for seclusion.

John Campbell, the hospital’s medical director for psychiatry, said restraints and seclusion are last resorts, and are used much more sparingly than they were 20 years ago, when they were standard practice. He said Maine Med will continue to work at reducing their use.

Campbell said psychiatric patients at Maine’s largest hospital include people who have “advanced dementia with behavioral disturbances,” and the hospital receives some of the state’s most serious cases.

“These are the people who are punching their fellow patients at the nursing home. Our numbers are going to look different than the average,” he said.

But Mehnert said more must be done in Maine. “There is nothing therapeutic about a restraint,” she said. “Using restraints can hamper the path to recovery.”

She said the state must provide more training resources and make it a goal to reduce use of restraints and seclusion. Alternatives include training staff members to better understand the diagnosis of each patient, giving patients enough space so they don’t feel crowded, and employing de-escalation techniques to avoid crises, such as talking slowly and calmly to avoid giving direct orders.

“Suggestions” by staff members may produce the same outcome for the patient, Mehnert said.

“We need to change the culture and the tools that we give to employees,” she said.

Mehnert used to work for the Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare, which she said prioritized the issue, kept its own statistics and has seen rates at hospitals decline. “Leadership matters on this issue,” she said.

Maine has not kept its own statistics.

Hospital officials told the Portland Press Herald that various factors can influence the rates, especially the makeup of the patient population.

“We take some of the most difficult patients in the state,” said Joyce Cotton, chief clinical and nursing officer for Spring Harbor Hospital in Westbrook. According to the federal data, the psychiatric hospital’s rates were 0.77 hours per 1,000 hours of patient care for restraints and 1.89 hours for seclusion, above the national and state averages.

Cotton said Spring Harbor Hospital recognizes that the methods should be used as little as possible, and 300 employees were trained last year on other ways to handle patients. The fruits of the training could be realized in the 2015 federal report, she said.

“This is a very important issue to us,” Cotton said. “We are committed to reducing the use of restraint and seclusion.”

Cotton said some of the data can be misleading because hospitals don’t have a uniform agreement on the definition of restraint, which can skew the reported rates. If a facility doesn’t report some of the more minor use of restraints, such as temporarily holding back a patient, its numbers will appear lower than those at a hospital that reports every incident.

Also, Cotton said, if a facility has security guards and a guard restrains a patient, it’s not counted in the numbers. Spring Harbor doesn’t have security guards, she said.

Cotton said a Maine legislative committee is expected to hold meetings on the topic this year.

At the Riverview Psychiatric Center in Augusta, a state-run hospital that treats private patients and people who are committed by the courts for violent acts, restraints were used at a rate of 0.62 hours and seclusion was used at 2.39 hours per 1,000 hours of patient care.

Last year, the center lost $20 million in federal funding and was criticized in a federal report after inspectors found that Kennebec County corrections officers used stun guns and handcuffs to control patients in the hospital. Its superintendent, Mary Louise McEwen, was ousted late last year by the state Department of Health and Human Services.

Riverview’s interim superintendent, Robert “Jay” Harper, wrote in an email response to questions that the hospital is working to reduce the use of such methods and has already started training employees.

“This (training) model requires a much higher level of commitment by staff to address the individual differences in each patient, including the potential for actions that might result in seclusion or restraint,” Harper wrote. Riverview “has also added a new group of employees known as acuity specialists who are skilled in taking action in the most difficult, acute situations.”

Harper said the hospital “anticipates a major reduction in seclusion and restraint incidences” in future years.

At Southern Maine Health Care in Biddeford, the rates were far below the national averages, with 0.2 hours for restraints and no reported cases of seclusion. Liza Little, the hospital’s clinical director of behavioral health, said the hospital decided a few years ago to emphasize training.

She said that understanding patients and what makes them agitated is crucial to heading off issues before patients become unruly. “It’s really important to find out what sets someone off,” Little said.

The hospital’s 12-bed psychiatric wing has had an influx of patients with more acute mental health problems. The patient population is more difficult, she said, yet the center’s rates went down after the training.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story