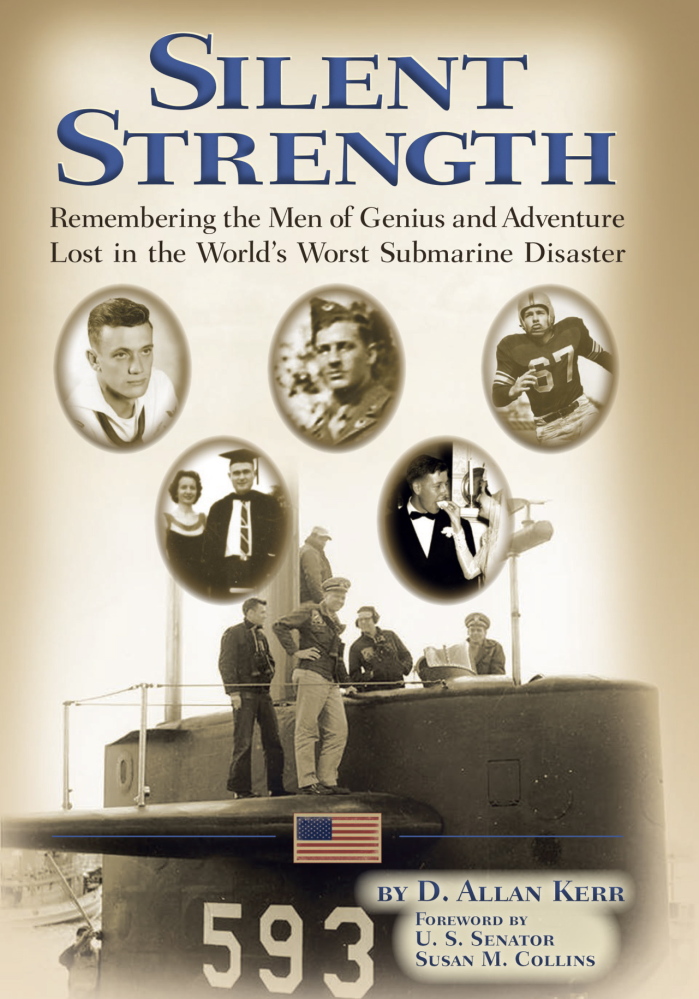

“Silent Strength” is a short, moving and factual tribute to the 129 officers, sailors and civilian technicians who lost their lives 50 years ago after leaving Portsmouth Navy Yard in Kittery, Maine, by submarine for sea trials.

Written by Navy veteran D. Allan Kerr and based on a series of articles and interviews with friends, family and colleagues of the lost, it cleaves to the facts about the lives of the men.

For those wishing a detailed history of the USS Thresher (SSN 593), background and possible causes, turn to Norman Polmar’s “The Death of the USS Thresher” (1964) or John Bentley’s “The Thresher Disaster” (1975).

Those who wish to know something about the lives, accomplishments, ambitions and families of the men killed and the prevailing attitudes of many Americans in the Kennedy era would do well to read “Silent Strength.”

The pride of Maine, New Hampshire and the United States, Thresher plunged to the bottom off the New England coast on April 10, 1963. This was the first nuclear submarine ever lost at sea and the disaster was reported almost immediately.

In the days before conspiracy theories, the first reports and subsequent analysis suggested piping systems in the ship had failed. Death would have come quickly, if not instantaneously.

I was 17 at the time, and the loss of the Thresher is one of those rare headlines forever engraved on my memory, along with the assassination of President Kennedy and Martin Luther King. These where unbelievable, stunning occurrences that were not supposed to happen in confident, optimistic post-World War II America.

Looking at D. Allan Kerr’s time capsule interviews brings the reader back to 1963 and to a true sea change in how we saw ourselves.

The men on the Thresher lost that spring day, and they all were relatively young men, were a rich sampling of the Greatest Generation and Korean War veterans, as well as Cold War volunteers.

They were patriotic, ambitious and mostly married to young bright women who were busy raising baby boomers.

Fred Philip Abrams, the civilian mechanical systems inspector, earned three battle stars during World War II, came home to marry his childhood sweetheart and began a family. Though Abrams had a phobia about water and confined spaces, he felt “compelled to go below the surface in a nuclear submarine, at the height of the Cold War.”

Steward Third Class George Bracey, also was a decorated vet and one of three African-American crewman. He was a deacon in a Portsmouth church, a husband and father of seven children. At 43, he was one of the older men.

Lt. Cmdr. John Wesly Harvey, one of the youngest commanders in the service, had played serious football for the University of Pennsylvania and the Naval Academy and was on track for a splendid career.

Richard Roy Desjardins was in the postwar ROTC at the University of Maine, Orono, was sent to Greenland and got a civilian job at Kittery.

He married Elizabeth Hurd; they had two children and one on the way.

A new monument at Kittery Memorial Circle, with a 129-foot flagpole, marks the lives lost on the Thresher. “Silent Strength” introduces readers to the family members who lost husbands and fathers and brothers.

Not every family story is told, but all the men are remembered. The interviews and images create an important and touching portrait, an acknowledgment of loved ones who were able to mourn and somehow move on, with the rest of the nation.

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England.” He lives in Portland.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story