Alsatian wines bring me to a state of simplicity. They may contain spectacularly far-ranging and complex aromas and flavors, but the wines I love – and I love many of them – give an underlying sense that the extraneous has been scraped away.

Drinking them, I feel cleansed and exact. My language shifts to meet the accuracy of the wine. “This is so right,” I say. “Spot on. So pure. Honed.”

I’m not always sure what I’m responding to. Is it the soil, the climate, the estate, the grape? Of course it’s a mix, but in Alsace more than most other places, a widely held view suggests that the lines separating these factors are more clearly drawn.

Each of the bigger estates (such as the great Trimbach, Zind-Humbrecht, Weinbach, Hugel) is known for a distinctive house style, especially along the richness-to-fineness spectrum, and many lovers of Alsatian wine tend to stick with the house whose style most appeals to them.

Winemaking matters. But Alsace is unique in France for letting the grape lead. “Alsace” and “Alsace Grand Cru” are the only designated appellations in France organized according to particular varietals: Riesling, Pinot Blanc, Sylvaner, Pinot Gris, Gewürztraminer, Pinot Noir and a few others.

In the rest of France, place takes precedence. A wine is from Médoc, Bourgeuil, Madiran, Jura, Beaujolais or Chablis. The grape, even if only one variety is used to make the wine, is only a medium, a vehicle for the transmission of character straight from a particular nexus of latitude and longitude.

An additional complicating factor in pinpointing the origin of my very strong personal sense of Alsace is that the soils and microclimates are so varied. With vineyards running in a relatively narrow north/south strip, Alsace’s wine region lies on a geological fault bordered by the Vosges mountains to the west and the Rhine river to the east, which has thrown up myriad combinations of marl, schist, granite, limestone, chalk, sandstone and volcanic soil.

With so many grapes populating such a mosaic of soils at varying altitudes, manipulated to varying degrees by winemaking estates with divergent traditions going back centuries, you’d think the wines would taste uncertain, if not muddled. Yet the opposite is the case. They’re pure and true.

Perhaps this is due to meteorology: Alsace in general benefits from one of the most consistently dry, sunny weather patterns in all Europe. The steady sun helps produce incredibly ripe and even lush wines, especially the Pinot Gris and Gewürztraminers, but never sweet.

Traditionally, Alsace wines have been fermented completely, yielding fully dry wines. This contrasts with their German neighbors, where tradition (and cooler ambient cellar temperatures) halted fermentation to result in wines with sweetness.

Now, though, you can’t even count on nationality to determine a wine’s sweetness.

More and more German Rieslings are utterly dry and increasingly intense, while a growing number of Alsatian producers, in part to compensate for climate change that warms the grapes to untenably high must densities, are fermenting with a lighter touch and leaving some sugar in the wines.

How do you know which is which? Only by tasting. The labels don’t indicate sweetness or even ripeness of the grapes when picked. These guys are from France, after all, where laissez-faire was invented, as opposed to Germany where the will to organize and name is strong.

Christian Binner, esteemed director of the biodynamic pioneer Domaine Binner in Alsace, recently took a wonderfully poetic approach to this quandary, telling Levi Dalton in a podcast interview that “it’s not easy” to know beforehand the style of a particular Alsatian wine, but “well, is life easy?”

I’m on his side, especially when he elaborates to say that “it’s good to not have too many rules.”

The wines are too good to be turned off by the uncertainty, anyway. Delve into any number of these wines from some of the smaller, less well-known estates, many of them newly available in Maine.

Domaine Bott Frères Edelzwicker 2011, 1 liter, $17 (Mariner). All that talk of singularity, but I’ll lead off with Edelzwicker, which means “noble mix.” Edelzwicker, like “Gentil,” indicates a blend of grapes and is what goes out on casual tables first in Alsace. Often it’s unremarkable; the Bott Frères isn’t. This blend of Sylvaner, Pinot Blanc and 10 percent Gewürztraminer is a perfect white for a picnic or barbecue (especially given the size of the bottle): juicy, grapey, only slightly peachy and spicily floral.

Domaine Gerard Metz Edelzwicker 2013, $17 (National). This more complex Edelzwicker contains Riesling and Muscat in addition to the Pinot Blanc and Sylvaner. No Gewürztraminer, but it’s still intensely aromatic, direct thanks to the Muscat. Crystallized ginger, all sorts of white flower gardens, buckets of joy.

Metz is interesting. Eric Casimir, the domaine’s manager, told me that their Tradition line of wines is “not primarily about terroir” but instead meant to communicate the “pure expression of each grape.”

I’m not sure that’s possible, for what is a wine but the interaction of grape, soil and climate? The grape wasn’t built in a lab. Casimir’s comment, though, is what got me thinking about Alsace’s inimitable sense of directness.

Check it out for yourself, with Metz Pinot Gris Tradition 2013, $17 (National). I love fatty, buxom wines like these. The exotic flower and agave savors make it seem sweet, but it’s got a paltry three grams of residual sugar and is ideal for a meal with oily components and spices.

Metz Pinot Blanc Tradition 2013 ($17) is, like many so-labeled Alsatian wines, actually from the Pinot Auxerrois grape. It’s leaner and lighter than the Gris, but still drives its point home with conviction.

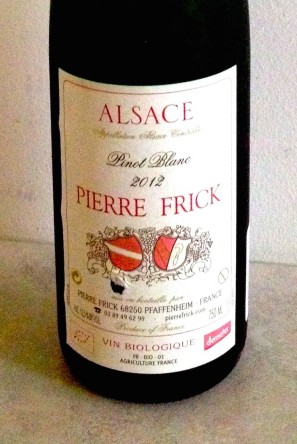

The wines from Pierre Frick are an entirely different matter.

Frick makes what most people call “natural” wines (very minimal handling, organic viticulture, sulfur almost never added, no filtration, etc.), and they express an astonishing kind of vivacity and openness.

If Metz’s Pinot Blanc is attempting a direct expression of a grape, Frick Pinot Blanc Classique 2012 $20, (Devenish) is after something altogether wilder and more open to interpretation. It has the bracing attributes of an untreated wine, with hints of funk and sour cherry, but is simultaneously so focused and packed with flavor that you stand back in awe.

Not awe at the wine so much as awe at the world itself. Drinking the wine feels like a walk through the woods, over hill and dale, open and exposed to the smells, sights, sounds and wind-feel of a Wordsworthian ramble.

And it is mere preface to Frick Sylvaner Bergweingarten 2007 ($27), whose age, botrytized tangy sweetness, full body, mineral structure and piercing length make it ideal for rich meat dishes. And with all it has going on, it still bears the hallmark dazzlement, clarity and delineation that seem the especial provenance of the wines of Alsace.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. He can be reached at:

soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story