Jack Kerouac is mostly remembered for one book, “On the Road,” and as one of the prime writers of the Beat Generation.

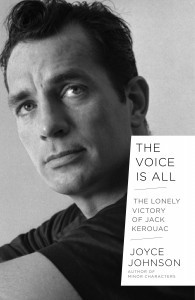

In “The Voice is All: The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac,” Kerouac’s one-time lover Joyce Johnson describes the long journey that developed him as a writer as he wrote in his second language (English), and how he found the voice that he used in “On the Road” by using the sounds and rhythms of his native French-Canadian tongue.

While earlier Kerouac biographies used his friends and contemporaries as sources, Johnson also used the Berg Collection of Kerouac’s papers at the New York Public Library as a source to provide information about his thoughts about being Franco-American. Johnson had a romance with Kerouac in 1957, and wrote “Door Wide Open: A Beat Love Affair in Letters 1957-1978” based on their correspondence.

In “The Voice is All,” Johnson says Kerouac is as much a Franco-American writer as a Beat writer, and added in a recent telephone interview that a still unpublished novella that he wrote in French-Canadian, “La Nuit Est Ma Femme,” still needs to find a publisher.

The Penguin Books paperback of “The Voice is All” was published earlier this month, is priced at $18, and is 490 pages long.

Q: You describe the Little Canada of Lowell (Mass.) in the 1920s to 1940s where Kerouac grew up. That would not have been much different from Little Canada in Lewiston or the French-Canadian areas of other Maine mill towns.

A: I don’t know much about those towns. I do know that a lot of French Canadians settled all over New England. There was a high concentration of them because of the textile mills.

Q: You call the language he spoke Joual, a term I had not heard. What is that specifically?

A: It’s called Joual up in Quebec, and here they just call it the French-Canadian language.

There were regional differences between people who settled in America and that language and the people who remained in Canada. The language kept changing and picking up new words, depending on where people were.

For example, in France, the potato is pomme de terre, but in French Canadian, it is patate.

When Jack was growing up in Lowell, it still was not a written language. Jack was one of the first people to try to a write that language down, which he did shortly after finishing “On the Road” in “Visions of Cody.” People might be especially interested in some writing he did in the French Language that preceded “On the Road,” a novella called “La Nuit Est Ma Femme,” which was never published. That book needs to be published, if only for its interest to scholars.

What he was doing in “La Nuit Est Ma Femme” was to bring into his writing his real internal voice, which was French, and that French sound was what gave his voice such a distinct quality.

Q: And that voice was quite different from the Thomas Wolfe-like writing he did in “The Town and the City?”

A: Because he was not a fluent English speaker until he was in his late teens, and he had a very early ambition to be a writer, he knew he had to learn English and write in the correct English way. His writing, in a way, was a translation going on inside his head from French into English. He didn’t let the French sound come into it until 1951.

Q: You say Kerouac is as much a French-Canadian writer as a Beat writer. Could you explain that?

A: The French Canadians have always claimed him as their writer. After he wrote “On the Road” and all of those books, he wrote about his Lowell childhood in “Dr. Sax,” “Visions of Gerard” and “Maggie Cassidy,” which are really a product of the childhood of a Franco-American. He did one last book, “Satori in Paris,” in which he went back to Paris to try to find his Breton ancestors. It wasn’t a successful quest, but he was obsessed, especially in his later years.

We always have focused on one book, “On the Road,” and then the whole Beat thing. Until recently, people have not explored the implication of his Franco-American heritage. That was very important to him but not something he spoke about, not even to people who were close to him. It was something he kept locked up until he began to write about it.

Q: The scroll version of “On the Road” (1951) has reached mythic proportions as a sort of stream-of-conscious masterpiece. But it was largely a rewrite of the earlier versions, wasn’t it?

A: It was more than a rewrite; it was a different book, although it had elements of early tries he made. There are people who believe that Jack never revised. His method of revision was start a book and put that version aside when he didn’t like it, and then to start again, using some elements of the discarded work. He had conceived of the book “On the Road” for a long time, even before he met Neal Cassady (the person on whom Dean Moriarty was based in “On the Road”).

Q: How different was the scroll version from the (published) 1957 version?

A: He wrote it as one long uninterrupted paragraph, and editors told him it couldn’t be published that way, so he broke it up into paragraphs and chapters. All characters had their real-life names. They deleted some sections, especially a lot of the sexual references. One particular editor kept angering him by chopping up his long, rolling sentences, but it is essentially the same book.

Q: What part of Canada did the Kerouac family come from?

A: Riviere du Loup (about 50 miles from the northern tip of Aroostook County, on the St. Lawrence River). His grandfather came from there and emigrated to the United States. He had a very large family, and the children kept dying, and he settled in Nashua, N.H.

Some of Jack’s aunts on his father’s side later settled in Maine. (Johnson did not know what towns in Maine.)

Q: You write about Kerouac’s multiple personalities. But the idea that he is supported by his factory-working mother and writes at her home, leaving occasionally to visit his friends in the city, is a bit strange, isn’t it?

A: He had a strong feeling of being very divided, and one of the big divisions was of being American and French Canadian. His mother provided him with a home in years when he hardly made any money. He couldn’t tolerate the routine of going to a job, was constitutionally unable to tolerate it. He did get some odd jobs, and did a lot of movie synopses for a couple of companies, for which he was paid $25 or $35.

His mother provided him with a home when he was working on his first novel. He promised his father he would take care of her and buy her a home, which he did right after the success of “On the Road.” But he did have a spoiled existence when he was living with her in an apartment in Queens. He was a very young man, living an austere existence, holed up writing every day and counting how many thousands of words he wrote, and then he would go into the city and drink a lot, and then go back to Queens. People don’t associate discipline with Kerouac, but as far as his writing went, he was very disciplined.

Q: How important were the Kerouac papers at the New York Public Library?

A: They were immensely valuable. They provide a lot of insight into his development as a writer and his feeling about being Franco-American. Until these papers became available thanks to the Berg Collection, a lot of other books were based on other people’s visions of Kerouac — and we were lucky to get them when we could — but these were Kerouac’s visions of himself.

Tom Atwell is a freelance writer living in Cape Elizabeth. He can be contacted at 767-2297 or at:

tomatwell@me.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story