Sandra Watson heard terrifying words from her son, Dylan Young, 13, as he slid into the back seat of her car when she picked him up from school in Augusta one day in early March.

“Mom, I feel like I’m dying,” Dylan said. “I smoked this stuff called Spice.”

He had vomited several times at school and felt progressively worse throughout the day before the school nurse called Watson to come get him.

“I had to stay as calm as possible, so he wouldn’t feel any worse than he already was,” Watson said. She rushed him to the doctor’s office, which immediately redirected Dylan to the emergency room at MaineGeneral Medical Center in Augusta.

” ‘I’m dying.’ That’s something you never want to hear your son say,” Watson said, her hand trembling as she picked up a coffee cup during an interview Tuesday.

Dylan spent four days in the hospital recovering, and he said doctors told him he could have died had he not come to the hospital.

“I was thinking that I didn’t want to die this way,” said Dylan, who is going into eighth grade.

Spice is a synthetic form of marijuana, and is sold legally in some convenience stores and other retail outlets. But it will become illegal in September under a law passed by the Legislature earlier this year.

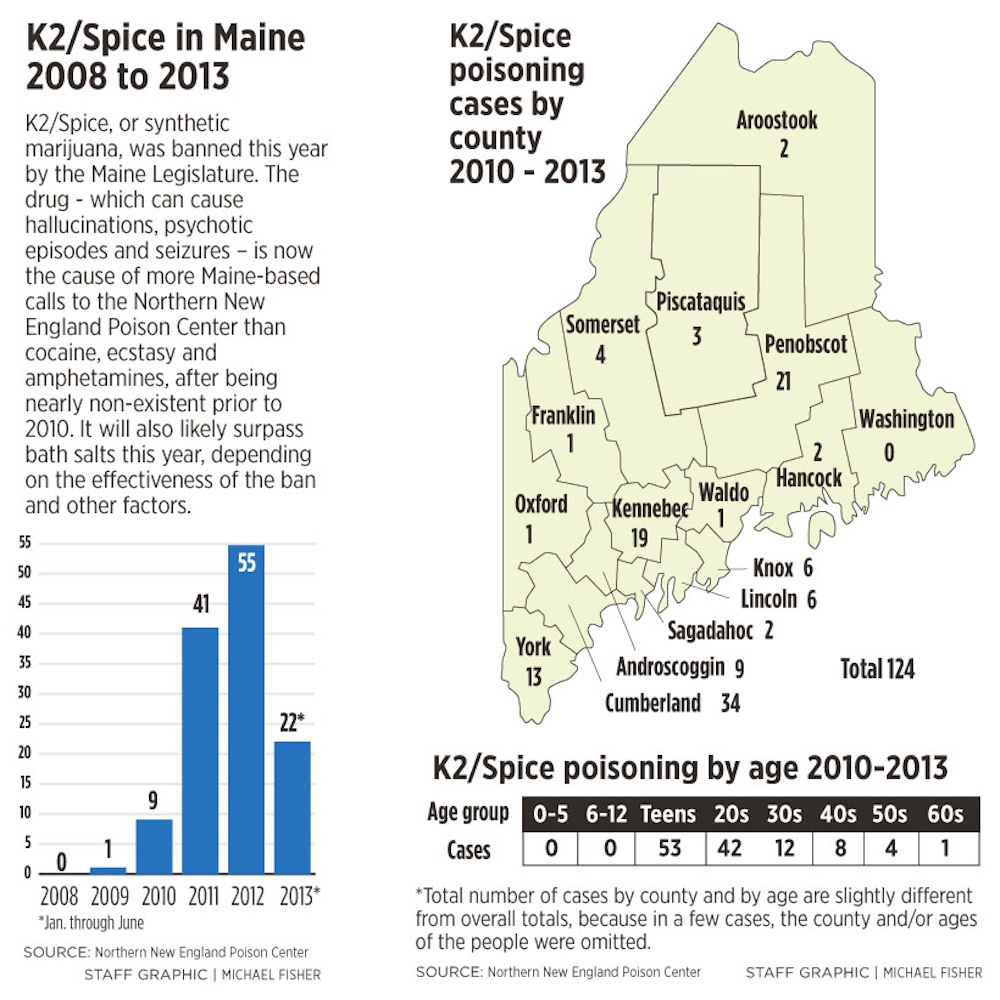

The ban comes after three years of increases in the number of Spice intoxication cases referred to the Northern New England Poison Center. Spice referrals have eclipsed those for cocaine, ecstasy and amphetamines, after being nearly unheard of in Maine before 2010. In 2013, Spice, also known as K2, will also likely surpass bath salts in Maine poison center referrals, although that’s mostly because of a sharp decrease in bath salts cases.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that Spice is the second-most-popular illicit drug in high schools nationally, behind marijuana.

The poison center reported 55 Spice cases in 2012. Although 2013 numbers to date are down slightly from last year, they are on track to be similar to those for 2011 and still high compared with other stimulants, according to the center.

Poison-center referrals mostly come from hospitals, but some have been called in to the center’s emergency phone line by individuals.

When he was admitted to the hospital, Dylan’s heart was racing at 175 beats per minute, more than twice the normal rate, Watson said. It took three days for his heart rate to start coming down.

He vomited numerous times, hallucinated and, before entering the hospital, may have had a seizure. Food tasted like plastic.

Dylan said he tried smoking Spice with a friend, believing that it would be similar to marijuana, which he had experimented with previously.

But after one long hit from a Spice-filled pipe, he said the high was far more powerful than marijuana. And then strange things started happening.

“My eyeball and hand felt like they were being squeezed, like when an anaconda captures its prey,” Dylan said. He said he started having convulsions and passed out for a few hours on a couch at his friend’s house.

He went home, ate three bites of dinner and went to bed. Then he started hallucinating.

“I saw zombies, and they were chasing me and trying to bite me,” Dylan said.

He said he kept his symptoms secret from his family because he didn’t want his mom to know that he had taken drugs.

Feeling somewhat better the next morning, Dylan went to school.

Watson said she noticed her son was pale and offered to allow him to stay home sick, but other than looking pale and not eating much dinner, she didn’t notice anything wrong. But at school, his symptoms worsened.

Dylan said he wanted to go public with his story because he doesn’t believe it should be legal to sell such a dangerous drug.

“Before I tried it, I thought it was basically the same as marijuana,” he said.

Watson said her son has become more reserved and aggressive since then. She said doctors are still evaluating him to see if there have been any long-term health effects.

Health officials say the symptoms that Dylan experienced are similar to other Spice cases reported around the state and nation. Some have resulted in heart attacks, although there are no known deaths in Maine attributed to Spice.

Media have reported deaths from Spice use in Texas, Indiana and Michigan.

“There’s a perception that Spice is not risky. But this is not just like having a little bit of ‘super pot,’” said Karen Simone, director of the Northern New England Poison Center. “We’ve had many cases of people showing up at the hospital, and a lot of times they’re scared.”

Simone said people don’t know what chemicals they’re putting into their body.

“It’s so new, we don’t know what the long-term effects are going to be,” she said.

Dr. Mark Publicker, addiction specialist at Mercy Recovery Center in Westbrook, said the center is just starting to see Spice cases, often in conjunction with other drug abuse.

Publicker said Spice users can suffer from psychotic episodes, panic, paranoia, hallucinations, rapid heartbeat and restlessness.

“Some people who have come in said it scared the hell out of them,” Publicker said.

Initially, detox treatment could include tranquilizers and anti-psychotic medications. Although Spice doesn’t induce a chemical dependency, people can become psychologically addicted to the high, he said.

“It’s an extreme state of euphoria,” Publicker said, explaining that the high is similar to ecstasy, although the drug acts in other ways like marijuana. “It’s five times more potent than marijuana.”

Withdrawal symptoms can include depression, anxiety, exhaustion and vomiting.

“The biggest problem with it is its availability to teenagers,” Publicker said. “It was sold right alongside the Slim Jims.”

According to the poison center, nearly half of the Spice referrals it received were from teenagers.

Although it often comes with a warning that it’s not for human consumption, there have been no age restrictions on purchasing Spice.

That made it seem to some like it was almost a benign substance, officials said. The marketing often targeted younger people, with one brand showing Scooby-Doo with his tongue hanging out.

“How it was marketed was confusing to people,” said Guy Cousins, director of Maine’s Office of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services. “The negative aspects were downplayed.”

Daniella Cameron, supervisor at the Preble Street Teen Center, a homeless shelter for teens, said usage seems to have peaked this winter.

“It was everywhere. It was rampant,” Cameron said. “It was really accessible and inexpensive.” Packs would vary in price, but often cost less than $10, officials said.

After some alarming cases, however, including three instances when teens had seizures either in the Preble Street center or nearby over the past year, usage seems to have decreased, she said.

“The youth have had so many negative experiences with it that I think the word has gotten out and it’s not being used as much,” Cameron said.

Portland Police Chief Michael Sauschuck said Spice availability seems to be decreasing, even though the ban doesn’t become law until September.

“Most stores, when they were told about the product, stopped selling it immediately, even before the ban went into effect,” Sauschuck said.

He said buying Spice was as simple as “buying a pack of gum,” and he hopes the statewide ban will help.

Spice producers have previously circumvented laws by slightly changing the chemical composition of the products, technically complying with the laws. A federal ban in 2011 proved ineffective because manufacturers tweaked the ingredients to comply with the law.

State Rep. Adam Goode, D-Bangor, who proposed the Spice ban, said the new law attempts to cast a wider net on chemicals used to make Spice and avoid some of the pitfalls of previous laws. He said he hopes the revisions will make it more difficult for Spice manufacturers to sidestep the law.

Sauschuck said making criminal cases stick against store owners will still be a problem, because the owners can always claim that they didn’t know the product was illegal. It’s a more believable defense than, say, someone selling cocaine.

“It will be hard to prosecute, but from a personal responsibility standpoint, they are required to know whether what they are selling is legal,” Sauschuck said.

From a public health standpoint, Simone said, Spice is not as much of a threat as heroin and may not need as much law enforcement attention. Portland police say heroin usage has increased over the past year.

But Watson said after knowing her son could have died, she and Dylan became motivated to do what they could to remove Spice from the stores. At least then it’s less available to teens, Watson said.

“It looks like all it is is potpourri, but in reality it’s a very dangerous drug,” she said.

Joe Lawlor can be contacted at 791-6376 or at:

jlawlor@pressherald.com

Twitter: @joelawlorph

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story