Originally published June 16, 2013

EUSTIS — On a Wednesday in April, Flagstaff Lake was draining away.

When full, it is the state’s fifth largest freshwater body, nurturing a local tourist economy and providing boating and swimming opportunities for thousands of residents and others visiting Maine.

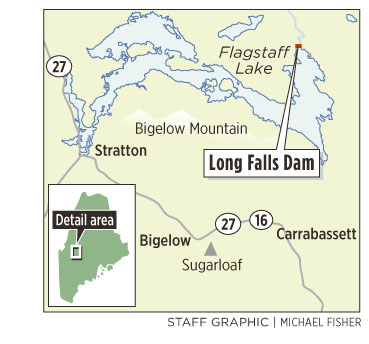

But on days like this — when the dam owner opens the sluiceways of the Long Falls Dam to generate power farther downstream — the lake begins to disappear, leaving behind thousands of acres of muddy and largely lifeless bottom. Docks are left high and dry and shorefront homes, camps and parks become isolated behind hundreds of yards of exposed, foul-smelling muck.

“They’re killing our area up here,” says Jay Wyman, a longtime selectman in Eustis, where many families moved in 1950 when the newly completed dam drowned their nearby hometowns of Flagstaff and Dead River.

People in the Eustis region fought for nearly a decade to defend their livelihoods, property values and tax base by pressuring state authorities to require the dam owner to keep the lake fuller in summer and early fall as part of its federal relicensing, which comes up for review only three or four times each century.

They’d sparred with the longtime owner, Florida Power & Light, from the hearing rooms of Augusta to the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

By the summer of 2011, it looked like they would win — until the state’s top environmental official stepped in.

That’s when the state commissioner of environmental protection, Patricia Aho — who just months before had been working as a lobbyist for the law firm which represented the Florida power company — met with Matthew Manahan, who was FPL’s attorney and Aho’s former colleague at Pierce Atwood, the state’s largest law firm. After the meeting, Aho’s department quietly did exactly what FPL hoped it would: nothing.

Despite detailed briefings from staff experts and a last-minute warning from the Attorney General’s Office, the DEP quietly let the clock run out, missing a critical federal deadline to influence what happens at the dam for another quarter-century.

Her spokeswoman would later claim it had been an oversight, suggesting staff had dropped the ball when, internal documents and interviews with former staff reveal, the ball had been taken from them and handed to Pierce Atwood’s client for an easy layup.

It is not an isolated incident.

A seven-month Maine Sunday Telegram investigation has found that commissioner Aho has acted against a range of consumer protection, pollution reduction and climate preparedness laws she had previously tried but failed to stop from passing the Legislature as a lobbyist for chemical, drug, oil and automobile companies. Present and former department employees say they have been pressured not to vigorously implement or enforce these laws, which were long opposed by companies represented by the commissioner’s former law firm.

Gov. Paul LePage has pledged to make the state more business-friendly and to reduce red tape. But in many cases, the Department of Environmental Protection has been scuttling laws in ways that benefit Aho’s old clients or those of past and present clients of another lobbyist embedded in his office: Ann Robinson, a top lobbyist at the Preti Flaherty law firm, who moonlights as the governor’s regulatory reform adviser and has drafted and promoted policies that would benefit her clients.

Internal documents and interviews with about two dozen current and former DEP employees reveal how the administration has systematically sedated some of Maine’s environmental laws.

Under LePage and Aho, the DEP has:

• Stifled the Kid Safe Products Act — a 2008 law to protect fetuses, babies and children from potentially damaging chemicals — by blocking efforts to bring more chemicals under the law’s jurisdiction. Many of the chemicals were produced by Aho’s former lobbying clients, who fought similar laws in Connecticut, California and the state of Washington.

• Recommended a rollback or elimination of certain recycling programs that are strongly opposed by Aho’s and Robinson’s corporate clients in the automotive, waste and bottled-water industries, who would suffer if successful Maine programs that make manufacturers responsible for certain products are replicated in other states.

• Presided over a dramatic downturn in enforcement of laws affecting developers, with initial enforcement actions in the Land Division falling by 49 percent under the LePage administration. (See related story: “They’re just not doing enforcement.”) Before becoming commissioner, Aho unsuccessfully fought to weaken many of the laws at issue as the longtime lobbyist of the Maine Real Estate and Development Association, or MEREDA.

• Purged information from the DEP’s website and clamped down on its personnel, restricting their ability to communicate information to lawmakers, the public, policy staff, and one another. (See related story: “Sources describe a department under duress.”)

“In both enforcement and in what we communicate to the Legislature, it almost seems like the commissioner is still a lobbyist for the clients she represented before she came to office,” says one current DEP employee, one of many interviewed for this story who did not want their names used for fear they would be fired.

Aho agreed to one interview with the Telegram but declined subsequent requests. In the interview, conducted in late February, the commissioner was asked about perceived conflicts of interest in connection with her former Pierce Atwood clients. Aho said that while she had been a lobbyist, two years had passed since she joined the department and that these were all former clients. She emphasized that she has met all disclosure requirements.

“That’s all out there, that’s public documents,” she said. The Attorney General’s Office “walked through to me how to enforce those issues” when she was appointed deputy commissioner in February 2011, and she cited examples of times in which she had declared her past lobbying associations in public hearings.

Robinson and Pierce Atwood managing partner Gloria Pinza did not respond to interview requests.

Senate President Justin Alfond, D-Portland, said Wednesday he was concerned but not surprised by the investigation’s findings. “It’s crystal clear that this governor and this commissioner have biases against certain programs and initiatives, and they constantly slow things down, change interpretations, and make things as challenging as possible,” he said.

• THE MESSAGE: CROSSING SPECIAL INTERESTS HAS CONSEQUENCES

Many of the nearly two dozen past and present DEP employees interviewed by the Telegram said they believed Aho was targeting diligent staffers at certain programs for isolation, elimination or reassignment, so their positions could be occupied with less knowledgeable replacements. (See related story: “Sources describe a department under duress.”)

Few were willing to talk on the record for fear of reprisals against themselves, their colleagues or present employers.

Several cited the product recycling experts who they say were shut out of the creation of the department’s report on product recycling programs. A two-time winner of the DEP commissioner’s award was reassigned from leading efforts to educate businesses on energy efficiency to be a drain inspector, others noted.

But most pointed to one case that is part of the public record: the reassignment of the key staffer responsible for implementing the Kid Safe Products Act.

Andrea Lani, who had run the program since its inception and had been a technical expert at the department since 1999, was given the largely clerical task of compiling public records requests and was replaced by a less experienced employee.

The reassignment occurred shortly after Lani had provided expert testimony to the Legislature on March 29, 2011, on the harmful effects of bisphenol-A, which was to be banned from baby bottles and sippy cups under the 2008 law. She did so as a private citizen and had taken time off to do so, as per policy at the department, which had recommended and shepherded the ban a few months earlier under Gov. John Baldacci. But her stance was counter to that of Aho, who had recently been appointed deputy commissioner.

Lobbying disclosures show Aho had fought passage of the Kid Safe Products Act in 2008 on behalf of AstraZeneca pharmaceuticals, the American Petroleum Institute and lead paint manufacturer Millennium Holdings. Just weeks before being appointed to the DEP, Aho was working as the principal lobbyist for the American Chemistry Council, which has opposed the law.

At the time of Lani’s testimony, the governor’s regulatory reform adviser, Preti Flaherty lobbyist Ann Robinson, was a registered lobbyist of one of the groups seeking to defeat the ban, the Toy Industry Association of America, even as she was helping draft and roll out the governor’s regulatory reform agenda. Robinson had also fought the Kid Safe Products Act in 2008 on behalf of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA, and drugmaker Merck, and the Toy Industry Association had hired her firm to lobby for passage of a 2011 bill that critics said would have effectively repealed the law.

Two days after Lani gave her testimony, Aho ordered her investigated to see “whether she had improperly used state resources in developing her testimony,” according to legal briefs filed in federal court. The investigation determined she had not violated any policies, but Lani was nonetheless reassigned to the records office shortly thereafter, leaving the Kid Safe Products Act in the hands of “a much less qualified individual who began working for the DEP in January 2011 at an entry-level clerical position,” according to the brief.

Lani sued Aho and another DEP official in federal court for allegedly having retaliated against her “in reckless disregard of her federal constitutional rights.” The state paid $65,000 to Lani and her attorneys in an out-of-court settlement reached in April 2012. Under the terms of the agreement, none of the parties is allowed to discuss the case or disparage one another. Lani remains the department’s public records coordinator.

Several sources said the incident has had a chilling and lasting effect on staff.

“People including myself were horrified that something that blatant would be done to a staff person who was within their legal rights and very well-respected, bright, hardworking and caring,” says biologist Barbara Welch, who resigned in January of this year and says she has filed harassment grievances against her supervisor, Samantha DePoy-Warren, a political appointee who was until recently the department’s communications director. “We followed her case and were astounded by what happened to her.”

“It was startling,” says Bob Birk, a landfill cleanup specialist who had accompanied Lani to the State House when she gave her BPA testimony and who retired from the DEP last September. “People felt they had to walk on eggs and literally keep their heads down.”

• THE TARGETS: ANY EMPLOYEES WHO DIDN’T ‘WORK WITH INDUSTRY’

DEP employees interviewed by the Telegram reported there have been few if any changes within the Air Quality Bureau, while the Land Division and the Remediation and Waste Management Bureau — which has oversight over the Kid Safe Products Act and product recycling laws — have borne the brunt of the staffing and policy changes.

According to a detailed list of recommendations Preti Flaherty prepared for LePage in late December 2010, its industrial clients were satisfied with the air bureau but did not have “a great relationship” with the Waste Management Bureau. The firm’s attorneys urged LePage to make a “serious effort” to rid the department of employees who didn’t “work with industry” on enforcement issues.

“The areas of the department with the least disruptive change are those who work with traditional, highly regulated communities: water licensing and air licensing,” says Malcolm Burson, who was DEP deputy policy director until November 2011. “They’re going about business the way they always have gone about business.”

“But you get into toxics or to land and it’s totally different,” he says. “That’s where the significant changes have taken place.”

Aho denied accusations that the staff changes were part of an organized effort to compel the departure or reassignment of particular individuals. “I think our department is doing great work, and I hope that doesn’t get lost in the debate about if we are doing something differently,” she said. “Yes, we’re doing something differently, but to actually enhance the work that they’re doing here and let them get out and be in touch with the environment perhaps more than in the other types and parts of their work.”

• THE STRATEGY: SEE LAWS BLOCKED, UNIMPLEMENTED, UNENFORCED

With staff at targeted programs of the department on tight reins, Aho moved against laws she and Robinson had been unable to defeat at the State House. Some laws went unimplemented, while others went largely unenforced.

Aho stopped the department’s efforts to add additional toxic substances to the two already slated for regulation under the Kid Safe Products Act by the Baldacci administration. An already completed proposal to ban a family of toxic flame retardants was left in the files, where it has sat since LePage’s election in 2010.

She also sought to foil product recycling laws that keep mercury and lead out of the state’s air, water and soil. At Pierce Atwood, the disclosures show, Aho had tried unsuccessfully to stop passage of the laws on behalf of mercury thermostat manufacturers, paper companies, automakers and other clients. (Maine is second only to California in the number of product categories covered by such laws, but a majority of states have at least one on the books.)

With Aho at the helm, the DEP created a report to the Legislature recommending these programs be considered for termination based on evidence critics charged was flawed and one-sided. No new products have been proposed for the program under Aho and LePage.

Aho’s actions also benefited the owners of the Flagstaff dam — Florida Power & Light and its NextEra Energy subsidiary — who received a new federal license last summer containing water level rules it preferred. They will remain in effect until 2036. (In March of this year, FPL sold all 19 of its Maine dams to Brookfield Renewable Power, a subsidiary of a Canadian asset management group, for approximately $760 million.)

• THE FLAGSTAFF LAKE EFFECT: HOW MAINERS LOST AN OPPORTUNITY

By the time Aho took over the department in the summer of 2011, the fight for Flagstaff Lake had been years in the making. But residents, negotiating with the company from a position of weakness, often came up short.

In many summers over the past decade, the Florida energy company FPL dropped Flagstaff’s water levels so low that by early August the local youth recreation program had to stop holding swimming lessons at the local beach and bused the children to a pool 20 miles away. Other residents reported foul odors wafting from the exposed lake bed and winds carrying silt and sand into a local elementary school and an elderly housing complex.

“You lose a couple feet here and people have to haul their boats,” says Wyman, the longtime Eustis selectman. “You pull three or four feet and you get mud flats. They drain it out too much and you get sandstorms.”

The problems kick in when summertime lake levels fall below three feet from what’s called “full pond,” townspeople report. At 4.5 feet below full pond capacity — the level the newly issued federal license allows in September — the Eustis end of the lake becomes a mud flat, with only the old channel of the Dead River containing any water. When the Telegram visited in mid-April, the Eustis end of the lake looked much as the town described it in regulatory filings: “a nearly empty bathtub surrounded by a dark ring.”

For the past decade, Flagstaff-area residents had fought to get more stringent water level rules written into the dam’s new license, which was up for renewal for the first time since the dam was built. The legal mechanism to do so was through the state DEP, which could impose such requirements under the federal Clean Water Act.

As early as 2004, federal records show, the town had asked the DEP and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to ensure that the dam’s new license require that the lake be kept at certain minimum levels in summer and early fall. That same year, the Board of Environmental Protection — an independent body that reviews environmental regulations — ruled that FPL’s winter drawdowns were too severe and, to protect aquatic life, should be limited to less than 9 feet below full pond capacity, rather than the 24 feet allowed under the proposed license.

There was a catch: DEP had to file paperwork by Nov. 15, 2011, or it would lose its seat at the table and, along with it, the means to modify the federal license, which FERC was otherwise ready to approve.

Aho missed the deadline.

Aho’s spokeswoman, Depoy-Warren, later claimed the failure to file the paperwork had been an accident, “something that was lost sight of during the transition of leadership.”

But according to both internal documents and Dana Murch, the staffer who oversaw DEP’s dam relicensing efforts for more than 30 years until September 2011, Aho and other key officials had all been fully and repeatedly informed about the dam and its deadlines.

Murch said he personally briefed the commissioner and other senior managers face to face on the approaching Flagstaff deadline that summer. “She certainly knew what the regulatory options were and where the project file was,” says Murch, who also highlighted the deadline in exit memos sent to staff.

Aho was also briefed on the issue by FPL. Department schedules and correspondence acquired by the Conservation Law Foundation through a public records request showed that Aho met in her office Aug. 4, 2011, with FPL’s attorney — her former Pierce Atwood colleague Matthew Manahan — and two FPL officials seeking to “update Pattie on the status of Flagstaff.”

DEP staff at various levels subsequently received reminders of the impending deadline, including one sent the day before to the staffer responsible for Flagstaff, Dawn Hallowell, by Assistant Attorney General Jan McClintock noting that if no action was “done by tomorrow, certification will be deemed waived by operation of law.” Hallowell forwarded the email to her supervisor, land and water bureau director Michael Mullen, meaning that even at the last hour, key staff were aware of what was about to happen.

“I think it’s disingenuous for the department to argue they did this in ignorance,” says Jeff Reardon of Trout Unlimited, which had fought for tighter water level targets. “We could have gotten a better situation, and it’s entirely possible Eustis and Stratton could have gotten a better summer target.”

“This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get a balance between hydroelectric energy generation and environmental values,” says Murch, the longtime DEP dam relicensing expert. “The legally proper way to have moved forward would have been to (do an) analysis to try to figure out what the appropriate new water standards would be to meet all needs and impacts. Find out how much environmental bang you get for each foot of water you don’t draw down from the lake and what the negative impacts are.”

“They chose the sit-on-your-hands-and-do-nothing option,” he adds.

The result was something of a slam dunk for FPL and anyone else who owns the dam between now and 2036, when the new license expires, as it killed more stringent limits on drawdowns, both in summer and off-season.

“Once the state made that decision there was no longer any legally binding obligation on the federal agencies or the dam owners to listen to what anybody has to say in Eustis or any other community,” says Sean Mahoney, executive vice president of the Conservation Law Foundation. “It all comes down to money: Having to do studies, having to do recreational things, having limits on what they can draw down affects how much power they can generate and how much money they can get for their shareholders.”

“By DEP waiving their authority, it gives the owner the best of all worlds: a non-appealable order that they needn’t change or defend and they don’t even have to pay for studies,” Reardon says. “It’s less expensive, more secure and gives them more authority.”

The governor appears fully supportive of Aho’s handling of the issue. Asked whether LePage had any concerns about the DEP having waived its powers under the Clean Water Act at Flagstaff, the governor’s communications director, Peter Steele, gave a one-sentence written response: “The Governor is confident that DEP is appropriately managing the delegated (Clean Water Act) program.”

Aho declined to be interviewed about Flagstaff and many other issues raised in this investigation. In mid-April, DePoy-Warren said DEP would not comment or respond to any further questions on this or other issues, saying she and Aho would “instead focus our efforts on the protection of our environment as the people of Maine expect us to do.”

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story