WASHINGTON — In a contentious climax Wednesday to a series of congressional hearings, a key IRS manager invoked her right to not testify about the agency’s targeting of conservative groups, igniting howls from Republicans and sparking a threat to bring her back for another round.

Deprived of a crucial witness, members of Congress from both parties alternately grilled and scolded former Commissioner Douglas Shulman about the Internal Revenue Service’s improper screening of conservative groups applying for tax-exempt status.

Although new details and documents have emerged about how IRS staff scrutinized organizations for political activity, the three hearings on three different days turned up no evidence that the aggressive screening stemmed from partisan motives or was ordered from above, either by the White House or by senior IRS management.

The hearings, launched by the release last week of a scathing inspector general’s report, instead have painted a picture of a bungling agency in which top managers in Washington were largely out of touch with how their staff in a Cincinnati field office was handling applications for tax exemptions.

Many questions have not been answered, including how the improper screening started, why it continued on and off for two years, and why top IRS officials did not reveal it for more than a year despite pointed questions from Congress and loud complaints from the targeted conservative groups.

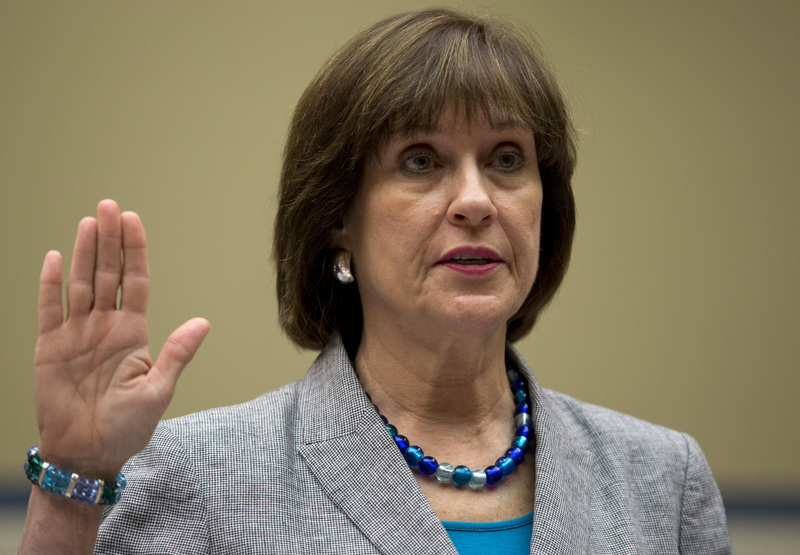

Manager Lois Lerner, who still supervises the IRS staff that handles those applications, and Shulman appeared Wednesday before the Oversight and Government Reform Committee, but provided little illumination.

Lerner, who revealed the inappropriate targeting two weeks ago, read a statement saying she did nothing wrong, then invoked her Fifth Amendment right to not answer questions. “Because I’m asserting my right not to testify, I know that some people will assume that I’ve done something wrong. I have not,” she said.

Her decision did not sit well with Republicans who are angered that conservative groups, including local tea party organizations, faced intrusive questions and long delays when they applied for nonprofit status.

“Ms. Lerner has invoked her constitutional rights not to answer our questions about her involvement or the IRS’ involvement, ironically, about denying others their constitutional rights,” said Rep. Michael Turner, R-Ohio.

Lerner, noting that the Department of Justice had launched a criminal investigation, said her lawyer advised her not to testify.

It is relatively rare for witnesses to invoke the Fifth Amendment. In April 2012, a federal official refused to answer questions about a lavish conference in Las Vegas. And a year earlier, executives of Solyndra invoked the right during a congressional investigation of federal grants to their failed solar-energy firm.

The oversight committee chairman, Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., excused Lerner, but said he may ask her to appear again, on the grounds that she may have waived her rights by first offering a defense of her actions.

The IRS did not respond to questions about Lerner.

“It’s important to find the facts before you hold people accountable,” White House spokesman Jay Carney said Wednesday when asked why Lerner was still at the IRS.

The new acting commissioner, Daniel Werfel, started Wednesday. President Obama asked him to report back in 30 days on what action he had taken to hold accountable any staff who acted inappropriately. “There is a commitment here to get to the bottom of what happened,” Carney said.

Also testifying Wednesday was the first Obama administration official, Deputy Treasury Secretary Neal S. Wolin. He said he learned that an inspector general’s audit was under way in 2012, but did not receive any details from J. Russell George, the Treasury inspector general for tax administration. “I told him that he should follow the facts where they lead. I told him that our job is to stay out of the way and let him do his work,” Wolin said.

The oversight committee staff has begun questioning IRS officials who were directly involved with supervising screeners of applications for tax-exempt status. One of those officials, Holly Paz, said she first uncovered the improper screening in June 2011. She said the employees in Cincinnati didn’t realize that using terms such as “tea party” to single out applications crossed the line.

“They were not even aware of, you know, politics,” she said, according to oversight committee staff. “Being outside of Washington, it was not something that they followed or had interest in.”

Many of the groups were sent letters with intrusive requests for information, such as lists of donors and details of their conversations at their events. Paz told the staff that no IRS managers looked at those letters before they went out, a practice that has since been changed.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story