JAY — Foster parents Marie and John Beaulieu are on the front lines of a funding crisis in Maine’s foster care system that has been attributed, at least in part, to a sudden and surprising increase in drug abuse among young parents who are neglecting their kids.

The Beaulieus worry that the state will reduce or eliminate support for the four foster children they’ve taken into their home in the last decade. A major culprit in the rising demand for foster care is a new type of synthetic, sometimes-hallucinogenic stimulants known as bath salts, child welfare officials say.

But an investigation by the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram found that the connection to bath salts, while headline-grabbing, is anecdotal at best and that child welfare officials really shouldn’t have been caught off guard by the rising number of kids in their care.

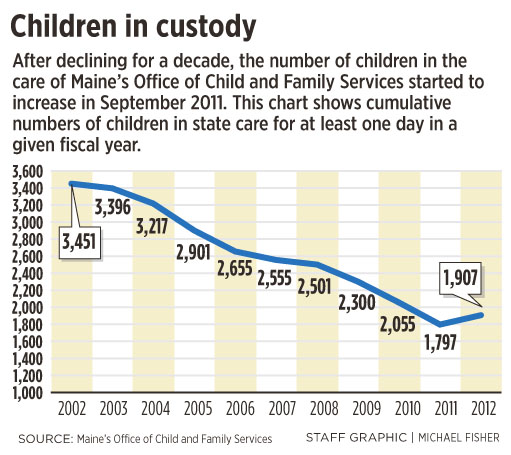

A decade-long decline in the number of kids in state custody started to reverse in September 2011, and child welfare officials can’t say exactly why, largely because they rarely analyze their own records in depth. And some of the state’s most vulnerable children and families may suffer as a result, including the rapidly rising number of babies in Maine who are being exposed to illicit drugs in the womb.

Legislators and others say factors such as poor planning and cuts in other social services likely contributed to the crisis, adding as many as 500 unanticipated children to the foster care system and leaving child welfare officials $4.2 million short in the fiscal year ending June 30. A supplemental budget put a Band-Aid on the problem in February.

To prevent similar shortfalls in the next two fiscal years, Maine’s Office of Child and Family Services is seeking a nearly 12 percent funding increase that’s expected to get serious scrutiny when the biennial budget review starts this week. Given a state budget crisis rife with competing demands and political agendas, however, there’s no guarantee that the extra funding will come through.

LITTLE HEARTS, BIG LOVE

The Beaulieus, both 45, are among about 1,200 licensed foster care providers and about 900 foster care adoptive parents across Maine.

Since 2004, the Beaulieus have taken in four foster children, now ages 18 months to 9 years, all of whom have serious mental and physical disabilities and illnesses because they were born to drug-addicted mothers. Shavar, the only child the Beaulieus will discuss publicly because they don’t fear for his safety, has a spinal curvature that’s slowly crushing his heart and lungs. Another of their foster children, a toddler, still struggles to suck on a baby bottle and requires several feedings each night.

And yet, the Beaulieus, who have three biological children, have adopted the two oldest foster kids, including Shavar, 8, and they want to adopt the two youngest if reunification with their birth mother fails.

In her various roles as mother, nurse, teacher, legal advocate and cheerleader, Marie Beaulieu is going morning, noon and night. John Beaulieu, a heating and ventilation technician, uses most of his vacation time to care for the kids during regular medical emergencies.

Still, Marie Beaulieu scoffs at the idea that she and her husband are doing anything difficult or extraordinary.

“My children are not burdens,” she said. “They’re amazing. They’re my little hearts.”

Despite the couple’s dedication to foster children with special needs, the Beaulieus worry that the Office of Child and Family Services will cut their adoption subsidy in the biennial budget.

They narrowly avoided a 25 percent reduction in their subsidy for the next three months, from $26.25 to $19.75 per day for each child. That’s how much some adoptive foster parents will lose as a result of a supplemental state budget passed in February.

The subsidy cut was part of a plan to backfill a $90 million Maine Department of Health and Human Services budget shortfall that was blamed largely on MaineCare, the state’s form of Medicaid. The state ultimately covered the Beaulieus’ subsidy with federal funds.

But the potential loss of $1,200 over three months would have been a big deal for the Beaulieus. Marie Beaulieu hates to talk about it, concerned that people will view the subsidy as payment for what she describes as a calling. But she still worries that their subsidy will be cut in the biennial budget; it’s happened in the past. If it happens again, she worries that John will have to take a second job.

“That’s my biggest fear,” she said. “There are no guarantees for tomorrow, and the kids’ needs are growing more intense with every milestone in their lives.”

MOUNTING DRUG ABUSE

If the demand for and cost of foster care in Maine spiked this fiscal year because of drug abuse among young parents, it’s doubtful that child welfare workers were surprised by it.

Experts in the field say the impact of parental drug use has been visible and mounting for years.

“They shouldn’t have been surprised,” said Beverly Daniels, executive director of Families and Children Together, a Bangor foster care agency that serves children with special needs, including a variety of behavioral and mental health issues.

In November, Daniels’ agency and the University of Maine School of Social Work got a five-year, $3.9 million federal grant to develop a program to help parents address substance abuse issues and keep kids out of foster care.

The growing need for some kind of assistance is measurable.

The number of babies born in Maine to mothers who used illicit drugs while pregnant has nearly quadrupled in the last six years, from 201 babies in 2006 to 776 babies in 2012, according to the DHHS.

Maine also has the highest opiate addiction rate in the nation, based on treatment statistics reported by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Maine has held this distinction at least since 2000, even as rates increased nationally.

In 2010, 4,083 Mainers sought treatment for abuse of non-heroin opiates such as oxycodone and hydrocodone, up from 768 people in 2000. That’s an addiction rate of 354 per 100,000 people, compared to 60 per 100,000 in the United States and 134 per 100,000 in New England.

Meanwhile, methamphetamine has had an increasing presence in Maine since 2005, followed by bath salts in 2011, when the synthetic stimulants were outlawed. Police uncovered 13 meth labs in Maine last year and four so far this year.

Bath salts arrests remain in the news, especially in the Bangor area, although reported overdoses dropped 71 percent last year, from 152 cases in 2011 to 66 cases in 2012, according to the Northern New England Poison Center in Portland.

Opiate abuse remains the larger issue, with a 32 percent increase in incidents reported to the poison center in the last year, from 99 cases in 2011 to 131 cases in 2012.

For Marie Beaulieu, the question of which drugs are driving parents to neglect their children is pointless. The three mothers of her four foster children each used multiple drugs. The oldest child had several substances coursing through her bloodstream at birth.

“When we first went to see her in the hospital, her tremors were so bad she was shaking the incubator,” Beaulieu recalled. “We did not know what we were getting into.”

A SYMPATHETIC CAUSE

Legislators learned about the foster care funding problem in January, when DHHS officials asked the Legislature for additional funding as part of the state’s supplemental budget. Therese Cahill-Low, director of the Office of Child and Family Services, reported a $4.2 million shortfall in the $45.9 million budget for foster care and adoption programs.

Cahill-Low said that 1,750 children were in state care in December, up from 1,469 children in December 2011. She expected that number to rise as high as 1,900 by the end of June, 35 percent higher than the 1,400 children projected in her budget.

Robert Blanchard, Cahill-Low’s data chief, said child welfare officials started noticing an increase in November 2011, after seeing steady progress in reducing the number of children in foster care from more than 3,100 a decade ago.

Cahill-Low pointed to a combination of contributing factors, including economic hardship and addictions to prescription painkillers and bath salts. She shared caseworkers’ anecdotes about delusional parents climbing trees, wielding weapons and neglecting their children in unprecedented circumstances. She said about half of recent neglect cases were linked to bath salts in particular.

When asked to provide concrete numbers to substantiate the bath salts connection for this story, a spokesman for Cahill-Low said her statements were based on “verbal reports” from caseworkers dealing with bath salts “hot spots” in Bangor, Rockland and Biddeford.

Still, legislators were concerned that child neglect was on the rise and moved to address a sympathetic cause immediately.

“You hear that and it rips your heart out,” said Rep. Richard Malaby, R-Hancock, a member of the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee.

Without further explanation from Cahill-Low or Blanchard, legislators covered the $4.2 million gap with a supplemental budget that includes additional state and federal funding and a $700,000 reduction in adoption subsidies, according to the Legislature’s Office of Fiscal and Program Review.

The proposed biennial budget for fiscal 2014 and 2015 would increase annual spending for foster care and adoption payments to care providers by nearly 12 percent, to $51.3 million per year.

But while legislators easily approved additional funding in the supplemental budget, members of the Health and Human Services Committee say they plan to scrutinize the biennial proposal.

“We’re going to take out the magnifying glass,” said Rep. Richard Farnsworth, D-Portland, committee co-chairman. “There has to be some data justifying these increases. They can’t just blame substance abuse.”

Now retired, Farnsworth was executive director of Woodfords Family Services in Portland for 18 years, overseeing the agency’s foster care programs for children with special needs.

Farnsworth believes cuts in DHHS funding have resulted in a “major failure” to provide necessary support services for birth parents to help keep families together.

“Substance abuse is a symptom of other issues,” Farnsworth said. “I believe there are a lot of other contributing factors here, and I want to see the numbers.”

RISKS IN THE HOME

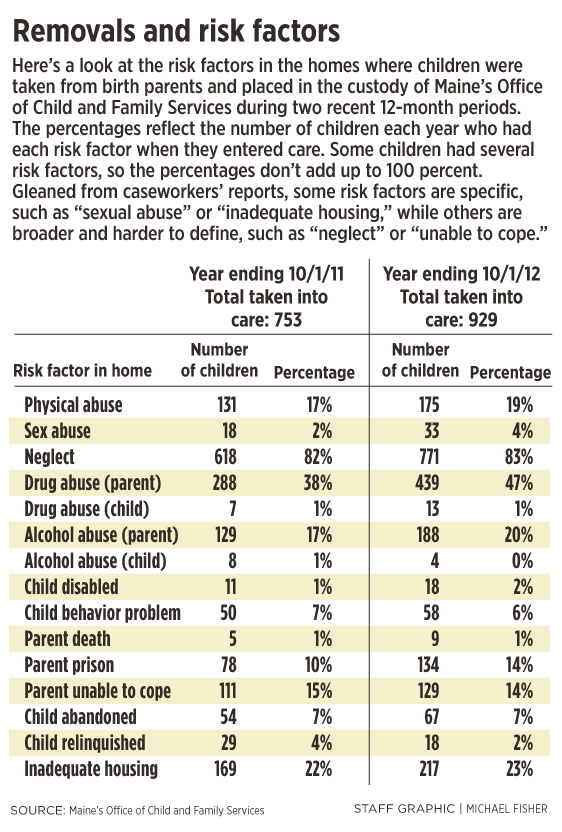

When the newspaper asked for data substantiating the claim of increased drug abuse among birth parents, Cahill-Low provided a one-page chart that her office generated in January.

The chart shows a 9-percentage-point increase in the percentage of children coming into foster care for whom parental drug abuse was listed as a risk factor in the home.

Parental drug abuse was a factor for 47 percent of 929 children removed from their homes in the year ending Oct. 1, 2012, up from 38 percent of 753 children in the year ending Oct. 1, 2011.

“There’s no reason to think this is going to stop,” Cahill-Low said of the drug-abuse increase. “They seem to be coming out with a new drug every day.”

Other risk factors — alcohol abuse, neglect, sexual abuse — increased by lesser amounts or remained flat, according to the chart. Parental alcohol abuse increased 2 points, to 20 percent of removals, while having a parent in prison increased 4 points, to 14 percent of removals.

But while the chart is informative, it’s lacking in many ways.

Limited to two years, the chart doesn’t allow comparison to previous years or identification of possible trends. It doesn’t specify the types of drugs that parents used, if that information was known, or show links among risk factors, such as neglect cases that resulted from substance abuse.

Broader social, educational, health and economic factors, other than inadequate housing, were excluded from the survey of risk factors. Some risk factors, such as “neglect” and “unable to cope,” are so broad they lack real meaning.

Overall, the survey was subjective and unscientific. Blanchard, the data chief, said the numbers were gleaned from caseworkers’ reports over the last two years. As a result, he acknowledged, risk factors could have been wrongly identified, included or excluded from the survey, depending on each caseworker’s awareness, accuracy and attention to detail.

Other factors also could be driving up the number and cost of children in the system, Blanchard said, including reduced family reunification and adoption rates and children’s individual special needs.

The state reimburses foster parents at six different rates, ranging from $16.50 to $65.62 per day, depending on each child’s behavioral and health needs, from minimal to severe.

The system has taken in more children than it has discharged in 15 of the last 18 months.

REVERSING GAINS

Maine’s child welfare system cost $120 million in fiscal 2012, including central office administration, caseworkers and nonprofit foster care agencies contracted by the state, according to Blanchard.

That works out to about $63,000 for each of the 1,907 children who spent at least one day in care during the budget year that ended June 30, 2012.

The increasing demand for and cost of foster care follows a period of recognized improvement in Maine’s system, including greater emphasis on placing children with relatives. So-called kinship care accounted for 32 percent of 1,829 children in state care in February, up from 14 percent of 3,082 children in November 2003, when the state started keeping track.

Maine’s foster care entry rate, reflecting the number of kids entering the system each year, dropped from three children per 1,000 in 2007 to two children per 1,000 in 2011, according to the federal Administration for Children and Families. From 2002 to 2010, the number of children in care on the last day of the federal fiscal year decreased by 22 percent.

Maine was No. 25 in the 2012 Right for Kids Ranking of state child welfare systems published by the Foundation for Government Accountability, moving up 14 places from No. 39 in 2006.

The ranking, based on 2010 data, recognized Maine’s efforts to provide safe, stable foster homes, reduce the number of children in foster care and promote adoption. However, the state was found lacking when it comes to preventing kids from entering the system, promoting family reunification and helping teenagers in the system.

Maine’s improvement mirrored a national trend and came several years after the 2001 death of 5-year-old Logan Marr of Chelsea, whose foster mother, Sally Schofield, a former state caseworker, was convicted of manslaughter for asphyxiating the girl with duct tape.

The recent increase in children in care comes as Cahill-Low said she has begun to overhaul agency contracting practices to meet federal guidelines, address a shortage of foster care parents for children with special needs and review programs to make sure children are getting necessary care.

She’s especially concerned about the estimated 35 young people across Maine who are technically in state custody but don’t have permanent placements, so they’re living on the street, in homeless shelters or “couch surfing” among friends.

“That, to me, is one of our most difficult challenges,” Cahill-Low said.

Amid the administrative upheaval, budget controversy and shifting family risk factors, foster care providers and others in the field worry about the impact on children.

“I worry, but I’m optimistic,” said Beverly Daniels, executive director of the Bangor foster care agency. “(Cahill-Low) has been willing to meet and work with us. She has shown great compassion for our kids. That hasn’t always been the case with people in her position.”

Whatever happens, Marie and John Beaulieu can be expected to make the best of it. That’s how they approach all of the challenges that face their kids.

When Shavar came to live with them eight years ago, his 4-month-old body was blackened by filth, and open sores festered where his arms rested against skin. He had spent so much time strapped into a car seat, with his head tilted to one side, that a flat area had formed on his tiny skull.

Later, he was diagnosed with a host of mental and physical disabilities and illnesses that doctors said would limit his life span to four or five years. And yet, four years ago, the Beaulieus eagerly adopted Shavar, making him a permanent part of their family.

“I was afraid someone else would adopt him,” Marie Beaulieu recalled. “In hindsight, probably nobody would have adopted a terminally ill child, but that’s what I thought at the time.”

Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story