FREEPORT – The sudden closing the Jameson Tavern, a favorite gathering spot for locals and travelers since 1801, has drawn surprising attention to the town’s specious claim that it was the “birthplace of the state of Maine.”

The motto is scrawled across the top of the town’s website and embroidered on the shoulder patches of Freeport’s police officers.

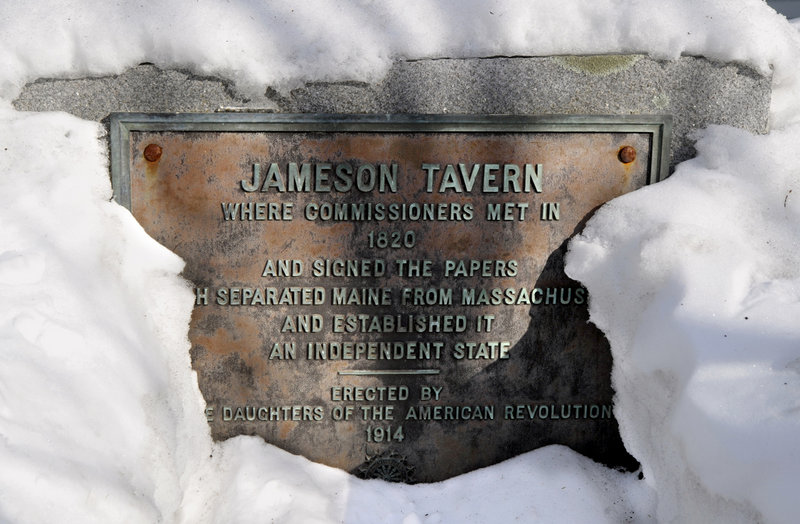

The town’s conjured role in Maine’s separation from Massachusetts in 1820 is even cast in bronze on a granite marker beside the tavern that was erected by the Maine Daughters of the American Revolution in 1914.

Through the years, several reputable historians have disputed the town’s claim, including staff members at the Freeport Historical Society. Still, the legend persists about a meeting at the tavern in 1820, when separation papers were signed to establish an independent state of Maine.

“It’s the town’s motto and it’s not true,” said Ned Allen, collections manager at the society. “This town was not in favor of separation. We don’t want to be mean, but we can’t perpetuate the story that it was the birthplace, even if the town wants it to be true.”

Despite a dearth of supporting documentation, many town officials have come to accept the motto as fact. Town Council Chairman James Hendricks said Tuesday that he had assumed the birthplace claim was true and declined to comment further.

“It’s just one of those legends people like to cling to,” said Johanna Hanselman, Freeport’s general assistance administrator. She has worked for the town since the mid-1990s and she couldn’t recall the motto ever being publicly questioned or reconsidered by the council.

“It’s the first I’ve heard of it,” said Police Chief Gerald Schofield. “We’ve had ‘Birthplace of Maine’ on our shoulder patches since the 1970s.”

Schofield said the motto used to be on the town’s police cruisers, but it was eliminated to save money. “Maybe it’s time to consider dropping it from the shoulder patches, too,” he said.

Owned by Jack Stiles of Bath for more than 30 years, the historic tavern at 115 Main St., next to L.L. Bean’s main store, closed sometime last week. A sign on the door Tuesday said the tavern “is closed until further notice.” Stiles didn’t respond to a request for an interview.

The tavern is considered historically valuable for its 18th-century architecture and its longstanding role in the social fabric of coastal Maine, but it’s not listed as an official historical landmark, Allen said.

The house was built about 1779 as a residence for Dr. John Angier Hyde, according to the tavern’s website. Capt. Samuel Jameson bought the property in 1801 and his wife ran a tavern there until 1828. Richard Codman bought the business and operated the tavern under his name until 1856.

The property was used for other residential and commercial purposes until Stiles bought and renovated the house in 1982, returning it to its former use as a tavern.

While many locals were surprised by the tavern’s closing, signs of trouble cropped up last November, when the main dining room was leased to Brahms Mount, a retail store for blankets and other fine textiles woven in Hallowell. Some townspeople have questioned whether the tavern, known for its chowder and other New England favorites, fell on tough times because more restaurants offering greater variety have opened in Freeport in recent years.

As news of the closing spread over President’s Day weekend, most media reports referred to the tavern’s historical significance as the birthplace of statehood.

However, a page on the Freeport Historical Society’s website gently debunks the birthplace “myth,” noting that prominent townsmen voted against separation six times starting in 1792. The last referendum was held on July 26, 1819, when the ballot was 107-103 against statehood.

And yet, every county in the District of Maine approved separation that day in July and a constitutional convention was held in Portland the following October. President James Monroe signed the bill for separation and statehood in March 1820.

Freeport’s disputed role in the push for statehood was chronicled in “Three Centuries of Freeport, Maine,” a book written by Florence Thurston and Harmon Cross in 1940. They recalled that several prominent opponents of statehood, representing Cumberland, Kennebec and Lincoln counties, gathered in Freeport just before the last referendum to organize a campaign against separation.

“They probably convened in the Jameson Tavern,” Thurston and Cross wrote. “In time all this could have grown into the story as it is told today.”

The plaque outside the tavern, which appears to be the only basis for the town’s motto, states that “commissioners met in 1820 and signed the papers which separated Maine from Massachusetts and established an independent state.”

According to Thurston and Cross, there was a joint commission of men from Maine and Massachusetts that met several times from 1820 to 1827 to iron out details of the separation. However, the meetings were held in Boston, Portland, Bangor and Augusta.

“There is no record of any meeting of these commissioners in Freeport,” Thurston and Cross wrote.

Alan Hall, a local historian who teaches at Yarmouth High School, wrote about Freeport’s mistaken motto on his blog, “Focusing on Yesterday.”

“It’s amazing to me that town officials have been told by their own historians that it’s just not true and they refuse to believe it,” Hall said Tuesday. “It’s stunning the degree to which the town is wed to the idea of being the birthplace of statehood.”

Hall said he hopes Freeport officials decide to drop the motto before Maine celebrates the bicentennial of its statehood in 2020.

If not, as Hall wrote in his blog, the motto will continue to “sail on through popular belief propelled only by local pride and wishful thinking.”

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story