New data shows that Maine’s high school graduates are less likely to need remedial courses in college than other students across the nation.

LePage administration officials said the numbers are “not acceptable,” but the state teachers union praised them as showing that Maine schools are succeeding.

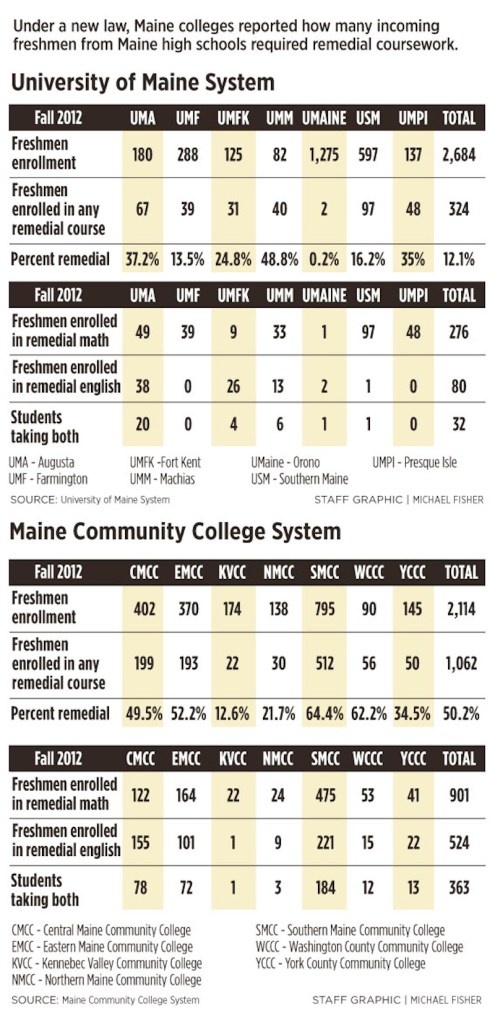

Data on freshmen coming into the University of Maine System and the Maine Community College System, available for the first time under a new state law, shows how many Maine high school graduates need remedial courses — at an annual cost totaling about $2 million for those students. The courses help students fill in knowledge gaps or improve skills so they can move on to college work.

Gov. Paul LePage will propose legislation in this session to “hold schools accountable” for their graduates who need remedial courses in college, Adrienne Bennett, LePage’s spokeswoman, said late Wednesday.

“It’s clear we’ve got a problem,” said Bennett, who provided no details of the proposed legislation.

In July, the governor said he wanted to introduce legislation to require school districts to pay for their graduates’ remedial courses in college. Bennett would not say Wednesday if that is what the proposed bill would do.

The new data shows that 12 percent of this year’s freshmen in the University of Maine System who came from Maine high schools needed remedial work.

By comparison, the average in New England ranges from 24 percent to 39 percent, depending on the type of four-year college surveyed by the U.S. Department of Education.

Maine’s community colleges reported that 50 percent of this year’s freshmen from Maine high schools needed remedial courses, compared with an estimated average of 60 percent nationwide, according to numerous studies.

The college systems’ remediation rates for all students were slightly higher than those for just Maine high school graduates. In 2011, the University of Maine System had 18 percent of students in remedial classes, and the Maine Community College System had 51 percent.

“This proves our public schools are succeeding and we should continue to invest in a system we know produces positive results,” said Lois Kilby-Chesley, president of the Maine Education Association, which represents teachers.

As for possible legislation, Kilby-Chesley said she won’t have any opinion until she knows what it might say.

“I don’t think that our students should be political pawns,” she said. “We should be thinking about what’s best for kids and getting what’s best for kids in the classroom.”

And that, she said, means money, reiterating the union’s call for the state to provide 55 percent of funding for public schools, a standard set by voters in 2004 that has never been met.

The data is creating just the latest conflict between LePage and Maine’s public school administrators and unions.

In November, LePage criticized Maine’s public schools, saying, “If you want a good education, go to private schools. If you can’t afford it, tough luck — you can go to the public school.”

A few months earlier, he said the reputation of Maine schools suffered nationally. “I don’t care where you go in this country — if you come from Maine, you’re looked down upon now,” he said.

The data, made available this week, is more proof that change is needed, said a spokesman for state Education Commissioner Steve Bowen.

“I find it mind-boggling that anyone can suggest 50 percent is a success,” said David Connerty-Marin, referring to the percentage of community college students who needed remedial courses. “It’s like saying, ‘Great, I’m getting a D but everyone else is getting an F.’

“More important than how we compare to the rest of the country is how we’re doing for Maine students,” he said.

Education researchers say interest in remediation has increased nationwide in recent years, for many reasons.

With budgets tight for states and schools, remediation is an additional financial burden for all parties. People expect all high school graduates to be college-ready.

Policymakers argue that tax money supports education through 12th grade, then subsidizes students again when higher-education institutions provide remedial courses.

Nationwide, it costs $1 billion to $3 billion a year to provide remedial instruction, according to the Community College Research Center at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

In 2011, a report by the University of Maine System showed that remedial courses cost students $1.5 million. In the Maine Community College System, the annual cost is about $400,000, almost all of it paid by the students.

In another study, the U.S. Department of Education found that fewer than one in four students who take remedial courses earn degrees or transfer from two-year to four-year institutions.

Maine’s public colleges released this year’s freshman data under a new state law that requires them to report remedial course numbers every year. In the future, the data will show whether those students stayed in school.

One education expert said the high school numbers are a good starting point to study why some graduates aren’t ready for college, but it’s too early to legislate policy based on the data.

David Silvernail, director of the Center for Education Policy, Applied Research and Evaluation at the University of Southern Maine, noted that one of Maine’s best high schools, Cape Elizabeth, sent six freshmen to the community colleges in the fall, and all of them needed remedial courses.

Of the 18 Cape Elizabeth graduates who entered the University of Maine System, none needed remedial courses.

Also, Silvernail noted, those 24 graduates represent only a fraction of about 100 Cape Elizabeth students who went on to college, because most didn’t go to any of Maine’s public colleges.

“The governor loves any evidence that says the schools aren’t working,” said Silvernail. “Unfortunately, that can’t help move things forward. People just get upset.

“If I was a policymaker, I’d say we’re above average but that’s not where we want to be, that’s not good enough,” said Silvernail.

Kilby-Chesley agreed that the high school data doesn’t fully explain why some graduates may need remedial courses in college.

“There are some children who have the ability to go on to higher education, but for a whole variety of reasons they aren’t ready,” she said. “Maybe because of their own priorities, or they aren’t terribly motivated. There are a lot of scenarios.”

For example, Portland High School sent 32 students to the University of Maine System, and seven needed remedial courses. The school sent 29 students to the community college system, and 23 needed remedial courses.

Deering High School in Portland sent 37 students to the University of Maine System, and six needed remedial courses; the school sent 34 students to the community colleges, and 28 needed remedial courses.

At Thornton Academy in Saco, 32 of the 48 graduates who went to community colleges needed remedial work, and six of the 56 who went to the University of Maine System needed it.

Administrators at Thornton noted that in recent years, the graduating class has grown 12 percent, and the school has increased the number of students going to college by 22 percent. Also, the school has recently started paying for students to take college placement exams, and is encouraging its students to go to college.

“The demographic that we work with has a significant percentage of students for whom the idea of attending college may not have been a family assumption, or a longstanding goal,” said Headmaster Rene Menard. “We believe that many of these students are definitely capable of college work. Our demographic has a lot of those students and we push them to reach, to think of themselves as college students.”

The college systems have multiple programs to reduce remediation rates.

Janet Sortor, vice president and dean of academic affairs at Southern Maine Community College in South Portland, said the college has formed partnerships with high schools, participated in New England regional conferences on best practices, and is working closely with the high schools and the University of Maine System to lower the remediation figures.

“It’s something we’ve really been grappling with,” Sortor said. “The real big concern is that this isn’t about blaming anybody. We’re working together to try to fix this. I hope what the Legislature does with this is thoughtful and more nuanced and a linking of arms for what we can do here.”

Sortor noted that remediation is needed mainly in math, often because high school students don’t know what career fields they may go into and don’t take enough math in high school. When they arrive at college, they’re behind.

Kayley Wilcox, a media studies major at USM, had to take remedial math and English courses, despite graduating from Bonny Eagle High School in 2009 with a 3.2 grade point average.

“I figured college was going to be different than high school,” said Wilcox, who started at USM in 2011 after working for two years. “In high school, I was fighting the whole math thing.”

That is a typical experience, researchers say. Students who can choose how much math to take may opt out before they have enough to be ready for college. That’s one of the reasons many policymakers are pushing for a more specific math and science focus in high school.

Other college students, like Wilcox, haven’t taken a math course for a few years and are out of practice.

Rosa Redonnett, chief student affairs officer for the University of Maine System, agreed, saying all high school students need algebra 1, algebra 2 and geometry to do college-level math.

“Too often, students come in with huge deficiencies,” Redonnett said. “They could be looking at (having to take) two or three (remedial) courses, and that’s ridiculous.”

Remedial courses cost the same as other courses, but don’t count toward graduation.

Both college systems varied widely by campus for how many students needed remedial course work.

Because of high academic standards at the University of Maine in Orono, there are essentially no remedial students — they simply aren’t admitted if they need those classes, Redonnett said.

But at the UMaine system campuses in Augusta and Machias, which are close to “open admission” institutions, remediation rates were 37 percent and 49 percent, respectively.

Sortor and Redonnett agreed that there are likely improvements ahead. Both noted that Maine is working to implement the rigorous new national Common Core curriculum, meant to improve performance in subjects such as math and reading.

State Sen. Brian Langley, R-Ellsworth, who serves on the Legislature’s Education Committee and is a former chair of that panel, also was pleased with the report.

“It tells me that students are being better prepared to meet the challenges of university work,” he said in a prepared statement.

Staff Writer Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

ngallagher@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story