WINDHAM – Sen. Bill Diamond of Windham has had an inside look at Maine’s war on child sex abuse.

But what he’s seen in the last eight years in the Maine Legislature, much of it spent as a member of the criminal justice and public safety committee, has left him disenchanted. He believes Maine’s sex offender registry is inadequate, sentencing is too lenient and that the public needs to wake up to the perniciousness and pervasiveness of child sex abuse.

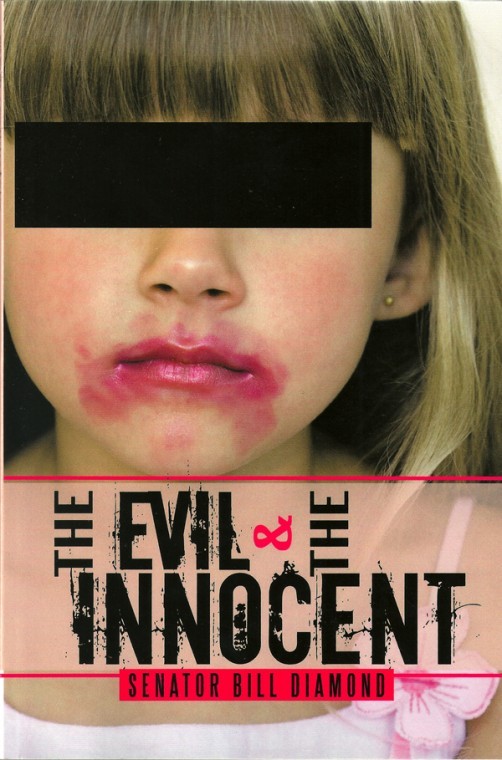

Diamond’s new book, “The Evil & the Innocent,” was published by Author House and is now available in bookstores and at Amazon.com. In the 125-page book released last month, Diamond, the longtime Windham resident and former Windham educator, interviewed those who survived abuse as well as abusers. He also interviewed those involved with fighting child sex abuse, taking readers on an in-depth tour of the issue, which Diamond says needs greater attention by the media and the public.

“There’s something wrong, we all know that. I didn’t get into psyche of a child molester [in the book], but there’s a disconnect where someone is attracted to little kids. But I’m trying to stop the bleeding, trying to educate people not so they overreact, but that they’ll be informed. That’s what I hoped to do by writing this book,” Diamond said.

Diamond spent most of 2011, about 11 months worth, writing the book. He said he felt the need to write about the sensitive topic partly due to inaction in the Legislature pertaining to a backlog of child sex abuse cases.

When elected to the Maine Senate in 2004, Diamond was elected chairman of the Legislature’s Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee, which includes jurisdiction over the Maine State Police. It was in that role that he first heard of the work of computer crimes unit, which operated on a skeleton crew dependent on federal grants at the time.

“In reviewing what they do, I found they did a tremendous job just piecemealing together stuff,” Diamond said.

In his official capacity, Diamond toured the unit, and while disgusted by the case matter – and maybe because of it – saw the importance of the unit’s work. Ever since, Diamond has been a staunch lobbyist on the unit’s behalf. He said that while they nab the bad guys, they “rescue kids,” which is their primary mission.

“They had a tour to show me what they did, which is rescue kids,” Diamond recalled. “They go online with the purpose of arresting people participating in this behavior. But, essentially, they’re trying to rescue the kids because every child porn image is a kid who is being molested. Every single one.”

In 2005, Diamond played a significant role in expanding the state’s sex offender registry, which was adopted in Maine in 1992 for law enforcement personnel only, but made available to the public in 1996. The Legislature, in 2005, voted to include those sexual predators who had been convicted of crimes dating to 1982. Diamond, in his book, questions the wisdom of requiring all sex offenders to register, with no qualifications or details given to the public as to the circumstance of each case. Along this line, Diamond explores the Easter murders in April 2006, in which a Nova Scotia man came to Maine after trolling the online registry for addresses of sex offenders. The death of the two men – William Elliot and Joseph Gray – points out the flaws of the registry, Diamond writes.

“William’s case is one that begs for a change in the registry, a change that distinguishes between high- and low-risk offenders. William Elliot was not a predator. In fact, the girl he had been seeing and was convicted of sexually abusing…actually came to William’s trailer one day and asked if she could stay with him,” Diamond writes on page 20.

The girl was also two weeks away from her 16th birthday and Elliot wanted to marry her, Diamond noted. While Elliot was convicted of having sex with an underage girl, the case is far different from others involving violence and beg for clarification, Diamond says, which the registry doesn’t provide.

“You go onto the sex offender registry now and think everyone on there is out to rape a little kid because they’re on the registry. And that’s not true. You have the no-risk, the medium-risk and the high-risk. So what I say in the book is that we need to change the registry so we are not all scared of everybody on the list,” Diamond said.

But he’s quick to add that many on the list are a threat and should still be in jail, not among the public. But the offenders at high-risk of re-offending are living among us, Diamond said, because the state’s sentencing guidelines are lax.

“I’d like to see stronger penalties. I’d like to see Maine have penalties equal the federal penalties,” Diamond said. “Whenever someone is accused, their lawyers try to get it tried as a Maine case, not as a federal case, because a federal case almost all the time has a more severe penalty. That’s not right and it needs to change.”

Diamond also wrote the book to get more awareness on the issue. And it seems to be working. Since the book’s release, Diamond has had interviews on television and radio news channels and in newspapers. He’s set to go on a book tour, as well, all in the hopes of getting people to think about the scourge of child sex abuse, especially since the introduction of the Internet, is having on the culture.

“It’s not the guy in the trench coat in the trees. It’s the guy and gal around us every day. Teachers, police, attorneys, couples. They have the best disguises because they’re disguised in such a way that none of us would recognize them,” Diamond said.

Diamond describes the Legislature’s efforts to fight child sex abuse as mixed since the existing registry is less than ideal and most laws, -such as prescribing where sex offenders can reside, are geared toward preventing random acts. He said government has little chance to prevent the abuse in the first place and says the public plays “a huge role,” since prospective abusers are already within their victim’s inner circle.

“A little over 90 percent who are sexually assaulted are by family or friends of family. So when we spend our time getting legislation [limiting sex offenders from living within] 1,000 feet of schools, it’s really not those people. The people we have to be concerned about are right in the family or know their victim somehow,” he said.

Diamond’s book is rife with examples of children being abused by family members or friends of the family. Some cases in the book are gleaned from Maine. He tells of the Sanford couple that lived next door to a family with a baby girl, whom they befriended and babysat for. Diamond said the couple “groomed” the unsuspecting family so they could gain access to the baby.

He also mentions the Casco father who, over a course of years, raped his two daughters, sometimes in exchange for small gifts or sweets.

While neighbors and family members are common targets for predators, so are students. Diamond recounts the story of the Milken Family Foundation award-winning teacher in northern Maine who was convicted of filming some of his 5-year-old students in lingerie and selling the images online in a peer-to-peer network.

Diamond also recounts the story of a former Windham High School teacher who was convicted for having 8,000-10,000 images of child porn catalogued on his personal computer.

“These people are all around us, and they’re people you wouldn’t suspect. They groom their victims. They gain the trust of parents or caregivers. That’s how they do it. But not all actually come in contact with their victim. A lot are online, paying to watch child porn online, which obviously feeds the network and has turned it into a multi-billion dollar industry. They’re just as bad in my book,” Diamond said.

And rather than simply recounting media accounts, which he criticizes for giving too little information on what actually takes place, Diamond interviewed several convicted abusers, including the former Windham teacher whom he didn’t name, and those who were abused. The most gripping of the personal interviews comes in the prologue, which focuses on the Joseph Tellier case, in which the Saco man abused and left for dead his next-door neighbor, 9-year-old Michelle Tardif. She barely survived the violent sexual assault. Tardif, now 32, recounted to Diamond the entire horrific episode.

“The interviews were very important. They really made the book if you ask me. It was difficult, obviously, but I felt it was important,” he said.

Research for the book has left Diamond with disturbing images in his mind that have caused nightmares. But Diamond is motivated to push on to bring about greater public knowledge of the issue.

“The biggest thing is awareness. The general public has to know exactly what’s going on. They have to know to what degree it’s been going on and they have to know that if we don’t build that awareness of what’s happening to the kids, then nothing’s going to change,” Diamond said.

While knowledge is best prevention, effective investigation is the next best thing, Diamond said. To that end, Diamond wants to see more money spent on the war against child predators. He takes some solace in the computer crimes unit getting three new staffers, which was approved for next year’s state budget, but says much more needs to be done in the effort. He said legislators were quick to assign more money to the unit when they heard of the case backlog, in which computer hard drives from suspected sex offenders are literally stuffed in an evidence locker awaiting examination.

“And that evidence is just sitting there and that means the predators and pedophiles are out on the street because no one’s been able to go in and make an arrest,” Diamond said. “So we have to provide the resources for the police, for the protectors, to actually go out and catch these people. And that’s what we don’t have now and that’s what we tried to do in this last Legislature where we hired two more detectives and one more forensic examiner.”

Diamond said the experience has forever changed him, especially since trying to package the disturbing subject into compelling book form.

“I dealt with it for years on committee, but when I started writing and researching it, that’s what kind of gets you. But I felt like the kids were saying, ‘Don’t forget me,’” Diamond said. “So it’ll always be with me, but I think that’s good because there’s no way I’m ever going to stop talking about this, until I die.”

Sen. Bill Diamond of Windham recently wrote “The Evil & the Innocent” to call attention to child sex abuse. (Courtesy image)

Sen. Bill Diamond of Windham recently wrote “The Evil & the Innocent” to call attention to child sex abuse. (Courtesy image)

Comments are no longer available on this story