BROOKS — When John Ford Sr. became a Maine Game Warden in 1970, he listened to his stepfather Verne Walker’s advice.

Walker, who had been a warden for 23 years, encouraged Ford to keep a diary of his adventures.

Someday, Walker told Ford, he could write a book.

“When I put on a uniform and went out the door, it was like I was going to the movies,” said Ford. “I knew I was in for a show every day. Sometimes it was humorous, sometimes it was a horror movie.”

And for years, in coffee shops, at lunch counters and at Rotary clubs, Ford has entertained people with tales of chasing convicts through the puckerbrush and of falling off float plane pontoons into ponds.

This spring, 22 years after retiring from his 20-year career as a warden, he’ll be reading excerpts from his 35-story book during a promotional tour.

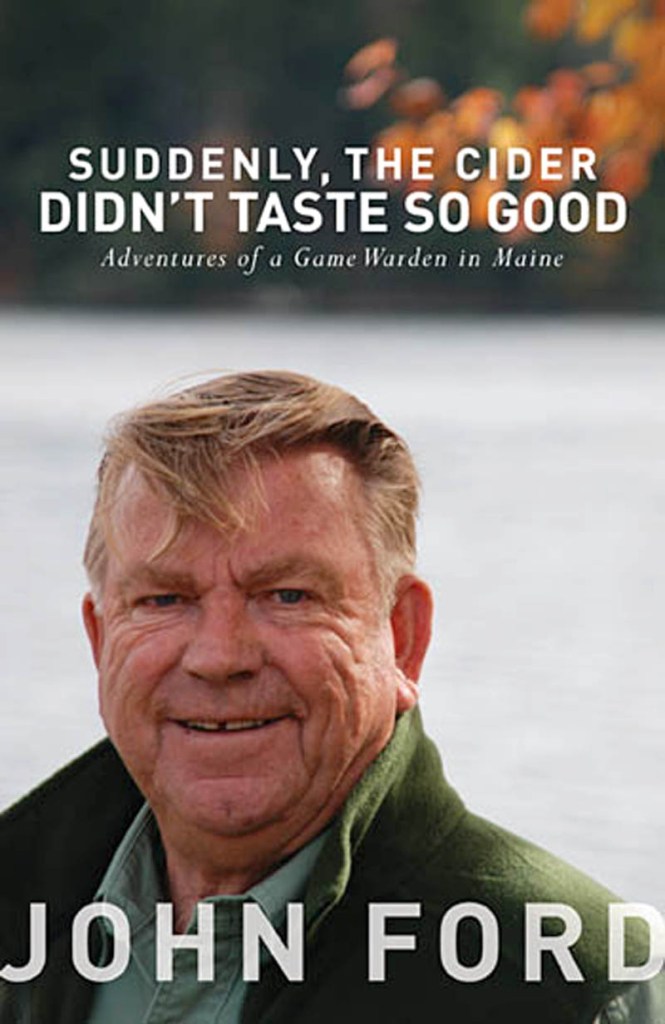

Islandport Press releases the “Suddenly, the Cider Didn’t Taste So Good, Adventures of a Game Warden in Maine” on Friday, April 20.

Throughout his career as a warden, or woods cop, when Ford filled out reports, he simultaneously jotted down notes about that week’s entertaining, exciting and heart-wrenching experiences.

While Ford is known throughout Waldo County as outgoing and gregarious, the 64-year-old said that wasn’t always the case.

The graduate of Sanford High School said he used to be shy. But when he landed in Burnham in 1970 as a new warden, Ford said he knew he had to change.

Sometimes that meant mingling at the corner market with rumored poachers who didn’t want him around.

Ford said he was assigned to patrol the Burnham district after windows at the prior warden’s camp had been shot out while his scared family members huddled inside.

Ford’s stepfather told him to keep things in perspective, be courteous and to not take law violations personally.

His direct advice: “They shot deer long before you arrived and they’ll shoot deer long after you’re gone.”

Honor, loyalty, compassion and trust are the stated values of the Maine Warden Service.

Ford could add humor to the list.

He said humor helped him appreciate his job, as well as the characters who occasionally ran afoul of the law.

“It’s not all black and white, you have to use judgment,” he said. “I generally erred on the side of the sportsmen. You have to be able to laugh at yourself.”

Ford wrote about a flight he took early in his career with Warden Richard Varney, the pilot.

“The steady drone of the engine, along with the constant dipping up and down . . . was taking its toll,” Ford wrote. “Suddenly I wasn’t feeling all that well.”

Varney landed the floatplane on Unity Pond, also known as Lake Winnecook, and taxied toward a nearby canoe so Ford could get a breath of fresh air while he checked for fishing licenses and life preservers.

“Screwing my warden’s hat securely on my head, I suavely jumped down toward the pontoon,” Ford wrote. “The problem was I didn’t come close to landing on it. Instead, I shot straight down into the water and completely out of sight.”

Humiliated, “it was a matter of sheer survival that forced me to finally bob back up to the top where my warden’s hat floated directly above me,” he wrote.

As Varney and the women in the canoe laughed, Ford scrambled back onto the pontoon.

“There I stood with water pouring out of my holster and dripping off my head,” Ford said. “I had to have looked like a drowned duck in a swamp.”

In an effort to make it sound like he planned the plunge, Ford said, “I guess they’re legal, Dick. I didn’t see any hidden stringer of fish beneath their canoe.”

Ford also described finding an injured baby deer along a road in Monroe. He originally planned to shoot the wounded animal, but when he bent down “he licked my hand while I gently stroked its head.”

So Ford decided to take the deer back to his house.

Bucky, as Ford named him, regained his strength munching on apples and sleeping on cedar branches.

“Whenever I got near him, he’d wag his tail and run my way,” Ford wrote. “Occasionally, he’d gently butt me in the rear in a playful sort of way, indicating he wanted to have his head scratched.”

After several weeks, Bucky was healthy and ready to return to the woods.

For the trip to Baxter State Park, Ford put the tame buck in his cruiser’s backseat and off they went.

When Ford happened upon road construction, he said one flagger nearly fainted when he saw Bucky comfortably along for the ride.

“The dazed flagman acted as it I didn’t have a clue that Bucky was in the backseat. Rushing toward us, he kept shouting, ‘There’s a deer on your backseat.’ I felt like saying, ‘No s#@$, you roadside genius,’ but instead I remained as professional as I could.”

Danger of the job

Many of Ford’s stories are funny, but the danger of the job is clear in others, including a tale about a manhunt for two escaped prison convicts.

In the sweltering summer of 1981, Ford helped in a multi-day, multi-agency search for escaped prison inmates Milton Wallace and Arnold Nash in the Moody Mountain area in Searsmont.

Nash, a burglar, and Wallace, who had sexually assaulted and murdered an 8-year-old boy, were armed and trying to make it to Canada.

After one search dog was shot by the escapees, Ford, with Trooper Dennis Hayden and his dog, Skipper, surprised the convicts as they huddled in a swamp under a tarp during a downpour.

“Skipper lunged toward them with his teeth gnashing,” wrote Ford, who had his shotgun aimed at Wallace’s head. “It was clear to these men that at any show of resistance the dog would make bloodied slabs of hamburger out of them in a matter of seconds.”

When Ford took the men back to prison, an official told him that the escapees had carried the pamphlet “You Alone in the Maine Woods” with them.

Ford, who is also a wildlife artist, had illustrated the pamphlet years before.

Ford, who often worked alongside troopers as he did during the Moody Mountain manhunt, was made an honorary trooper in 1984.

And, after a vote of his warden peers, Ford was named a legendary warden in 2000, in part, for his efforts to halt night hunting.

After ending his two-decade career as a warden, Ford served two terms as Waldo County sheriff.

Writing career

Soon after retiring in 2004, he began writing a column about his adventures for the VillageSoup websites and papers as well as Northwoods Sporting Journal. His “Memories from a Game Warden’s Diary,” won first place for sports column in the 2007 Maine Better Newspaper Contest.

Ford said his columns serve as a record of sorts of the 1970-1990 era in the Maine Warden Service, which was established in 1880.

When Ford started in 1970, he earned $70 a week, shifts were six days on and two days off and wardens were on call 24 hours a day.

His issued equipment included a badge, .38-caliber handgun, compass and cruiser.

Today, millions tune to North Woods Law on Animal Planet, which shows “Maine’s elite game warden service as they navigate the Pine Tree State’s rugged terrain during hunting season.”

Their equipment includes four-wheel-drive trucks, boats, snowmobiles, ATVs, computers, portable radios, GPS, forensic mapping equipment, aircraft and night vision goggles.

The night-vision goggles would have come in handy for Ford on several of his overnight stakeouts.

They might have, for instance, prevented him from backing his cruiser into an abandoned cellar hole in a field or eating a spider that had crawled into his bag while he waited in the dark for poachers.

Ford, who lives in Brooks with his wife, Judy, said he’s excited that Unity College is a stop on the book tour — Ford bunked at Wood Hall his very first night as a warden.

Beth Staples — 861-9252

bstaples@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story