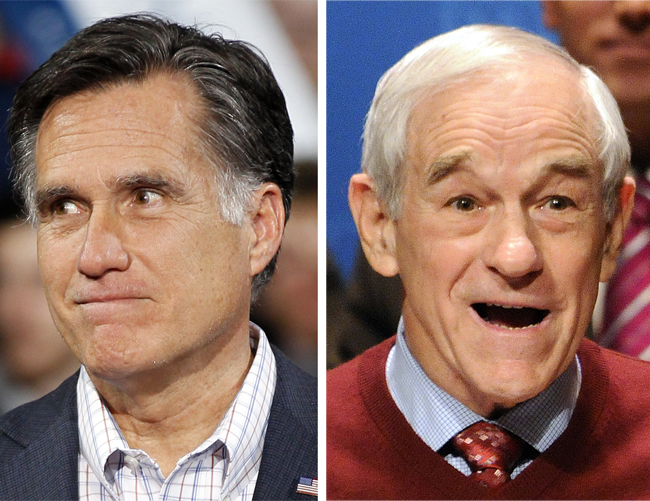

PORTLAND, Maine — Mitt Romney and Ron Paul rarely even acknowledge each other in the Republican presidential race, focusing their attention and attacks on rivals Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum instead. That curious detente is being tested in Maine’s caucuses this week, where Romney’s reputation as a political shape shifter is going head-to-head with Paul’s consistent libertarian views.

The caucuses began Feb. 4 and will continue through Saturday, when the state party will announce the results of the nonbinding presidential straw poll. Paul has campaigned hard in the state, and Romney has taken steps to shore up his position there to offset a potentially embarrassing loss following defeats in Missouri, Colorado and Minnesota.

Romney unexpectedly added two caucus appearances to his schedule Saturday morning, an indication that the campaign is concerned about the potential of another defeat in the low-turnout affair. And the significance also is great for Paul, who has staked his candidacy on winning at least a handful of smaller caucus states.

Santorum, who won the three contests earlier in the week, has not competed actively in Maine, nor has Gingrich. That leaves an unusually direct contest between Romney and Paul, pitting the former Massachusetts governor’s establishment support and geographic advantages against the Texas congressman’s relatively small but passionate band of activists.

In many ways, the two candidates could not be more different. While Romney has changed positions on a number of important issues including abortion, gay rights and health care policy, Paul has hewed to his small government message since entering Congress in 1978.

The Maine face-off also is renewing attention to the persistent deep divisions in the GOP — the more moderate, business-oriented wing represented by Romney and the restless tea party voters who’ve been receptive to much of Paul’s platform.

Romney’s aides say they do not view Paul as a threat to winning the nomination. But Romney and his team have also been mindful not to do or say anything that might anger Paul’s loyal supporters.

“I think he’s being very careful because he knows how important the Ron Paul voters are — they obviously represent a very different dynamic,” said Mike Dennehy, a former top aide to Republican John McCain’s 2008 campaign. “They are the most passionate and the most frustrated of any voters heading to the polls. And many of them are independents.”

To be sure, Romney and Paul do share some similarities.

Both have decades-long marriages — Romney and his wife, Ann, have been married for 43 years, while Paul and his wife, Carol, have been wed 55 years. The two couples each have five children and large broods of grandchildren.

Both Romney and Paul are physically fit and highly disciplined in their personal habits. They’re also religious — Romney is a Mormon, and Paul is a Baptist who leaves the campaign trail most Sundays in part to attend church services near his Texas home.

Both men are veterans of the 2008 Republican nomination contest and are on friendly personal terms, as are their wives, aides say. The relationship in part explains their unwillingness to attack one another.

Paul’s TV ads, which have included harsh, pointed critiques of Santorum and Gingrich, have been much easier on Romney. Paul’s campaign ran one ad casting all three rivals as “counterfeit conservatives,” but otherwise he has not criticized Romney with the same intensity as he has Gingrich. He slammed Gingrich for his work for the federal mortgage giant Freddie Mac, and he cast Santorum as a “corporate lobbyist and Washington politician.”

Paul has also defended Romney against attacks on Bain Capital, the investment firm where Romney made millions. Critics, including Gingrich, have criticized Bain for consolidating companies and laying off workers to make big profits for Romney and other executives at the firm.

“If he loses the election because he restructured companies, I don’t think that’s a healthy way to sort out the candidates,” Paul said in New Hampshire when asked about Romney’s history at Bain.

Romney won New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation primary, and Paul came in second.

Romney has returned the favor, occasionally praising Paul in debates for his understanding of health care. Paul is a former Air Force flight surgeon and obstetrician.

“You do exactly what Ron Paul said … you have to get health care to start working more like a market,” Romney said in a debate in December when asked how he would improve health coverage as president.

Romney reiterated that praise this week in a conference call with Maine supporters, saying Paul’s years as a doctor gave him real world experience Gingrich and Santorum lack.

For Romney, staying on Paul’s good side is also strategic.

Paul’s presence in the race weakens Gingrich and Santorum, making things easier for Romney, the field’s front-runner. Paul has earned more than 10 percent of the vote in every contest so far, except for the 7 percent he earned in Florida. And he’s finished in the top three in three of the first eight contests. Those are voters who might otherwise support Gingrich or Santorum, since there is little overlap between Romney’s voters and Paul’s.

Paul may have something more tangible to give Romney as well: delegates.

So far, Paul has earned just nine delegates, but he’s likely to accumulate many more because of the new proportional voting system adopted by most states. That means Paul may be in a position to arrange a transfer of some delegates to Romney at the Republican National Convention, which could be significant if Romney is locked in a tight race with another rival.

“If Mitt Romney remains on good relations with Ron Paul, they should be able to come to a polite agreement on how that will work,” Dennehy said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story