As a graduate student, Lillian Nayder studied the minor works of Charles Dickens.

While others studied his more notable books — the ones that made the 19th-century writer a household name and established him as a champion of the poor — Nayder thought Dickens’ lesser-known works told more about him personally.

“I was interested in learning about the other side of Dickens — Dickens the disciplinarian, the control freak,” said Nayder, chairman of the English department at Bates College in Lewiston. “You see the other side of him most strikingly with his family.”

Nayder’s interest in the other side of Dickens led her to research his wife, Catherine Hogarth. After 22 years of marriage and 10 children, Dickens forced her to leave their home, and accused her of being an unfit mother.

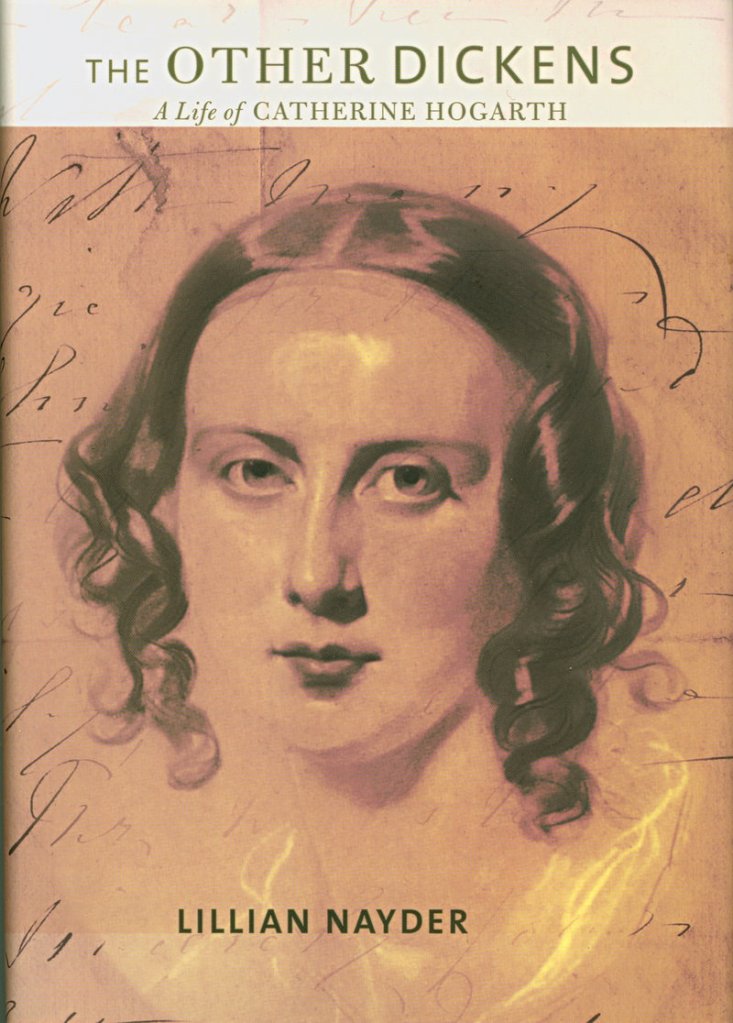

Nayder wanted to find out more about Hogarth, which led her to write “The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth” (Cornell University Press). The book came out in early November.

Q: When you started your research about Hogarth, what were you hoping to find?

A: I was interested in finding writings by Catherine and other family members, materials that would explain what happened. They were living together for 22 years, then (Dickens) took up with a woman who was the same age as his daughter Katie, 18.

They had an affair, critics argue, and in order to justify his behavior, and to force Catherine out of the house, he fabricated stories about her being “mentally disordered” and an incompetent wife and mother. I was anxious to uncover different sides to the story.

I found information in Catherine’s own letters, journals of family friends, legal papers and bank records. The bank has a record of every check Dickens ever wrote. Catherine clearly controlled a substantial amount of money at times, which is one sign she was not incompetent.

From letters, we know that Dickens’ own sister was on close terms with Catherine during the separation. Dickens’ own sister was socializing with Catherine.

Q: What were the most compelling pieces of information you found?

A: The testimony of these other people, like Dickens’ sister. Or the Dickens children, some who wanted to live with Catherine. As a wife in the 1850s and ’60s in England, Catherine didn’t have custody rights. And Catherine’s own letters, throughout her life, are quite articulate and rational.

Q: What happened to her when she left Dickens’ home?

A: She made a life for herself. She moved to a house near her sister, and helped her sister’s music career. Her sister was a vocalist and taught piano. She remained close to her parents and her children. One, Charlie, was 21 and lived with her after the separation.

She had a very active social life. Many of the people she knew with Dickens maintained a relationship with her. Even Wilkie Collins, who collaborated with Dickens, spent evenings with her. They separated in 1858, and she lived until 1879.

She was also a writer. She authored a cookbook that went through several editions. She was interested in cooking and entertaining, and was a very funny and social person. She loved to read and go to the theater, to the opera, to concerts.

I’m trying to show that she was a person unto herself.

Q: What do you hope people get out of this book?

A: I’m trying to explain the significance of a woman’s life, and to reconstruct a part of women’s history by looking at the significant issues Victorian women faced — such as custody rights and property rights. That’s a part of what the book does.

Staff Writer Ray Routhier can be contacted at 791-6454 or at: rrouthier@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story