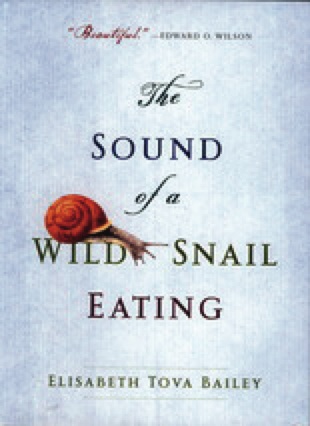

Some story lines defy the odds. A book about an ailing woman who befriends a bedside snail, for instance, might seem cloying and schmaltzy on the one hand, or satirical on the other.

In the case of Elisabeth Tova Bailey’s observational memoir, “The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating,” both woman and snail handily quash our fears. What starts as an improbable story becomes an irresistible one.

First we meet the author who, at 34, contracts a virus on a trip to Europe. She arrives home in Maine, lands in the hospital, and it’s downhill from there. Fevers, fainting, headaches — her condition worsens, turns life-threatening and eludes proper diagnosis. Bedridden for months, Bailey was suspended in limbo between sleep and slow motion.

Enter the snail. A friend came to visit one day, bringing a pot of wild violets with a woodland snail perched on a leaf. What appeared to be a gift of flowers was, in fact, d?r for the tiny gastropod. To the author’s puzzlement and surprise, the friend thought Bailey might “enjoy” a live snail.

So begins the quirky bond at the heart of this chronicle. Bailey observes the acorn-sized snail and becomes transfixed by its every painstaking pursuit. As the snail climbs up a terrarium wall or hangs upside down from a stem, she tracks its slow, cautious movement, oddly reminiscent of her own. While the author’s illness renders her barely able to roll from her right to left side in bed, the snail provides a hopeful mirror of sorts.

“Watching it glide along was a welcome distraction and provided a sort of meditation,” Bailey says. “My often frantic and frustrated thoughts would gradually settle down to match its calm, smooth pace. With its mysterious, fluid movement, the snail was the quintessential tai chi master.”

With this kind of proximity, perhaps, comes a tendency to wax anthropomorphic. Bailey wonders whether the snail “approved of its dinner” (portobello mushroom), “ponder(ed) its circumstance” or “appreciated” its sundry adventures. She even dares to title one chapter, “A Snail’s Thoughts.”

Just when it seems that the author has gone over the top, she’ll inject some bit of mollusk research that bolsters her stance. Indeed, we learn that snails have memory and can store new data about smells and tastes for months.

Bailey, it turns out, is hardly the first person to be captivated by a snail’s charms — before her came centuries of scientists, naturalists and poets, from Charles Darwin to John Donne. The creature’s probing tentacles and multi-purpose slime, its spiral shell that doubles as a mobile home, have long been sources of fascination. So, too, have the snail’s complex mating rituals and ability to close up shop and go dormant when food or weather prove unsuitable.

Although Bailey’s memoir is based largely on a year in her own life, several more years went into its making. Bailey combed the scientific literature and consulted with snail experts far and wide. The resulting book mingles her firsthand account with a pleasing array of gastropod history and science.

Nor do Bailey’s musings pertain only to lower species. As her neurologic illness slows the author to a virtual snail’s pace, she reflects on the incessant rush and clatter of our own kind. When friends would visit, their every movement — even waving an arm or tossing their heads — seemed extravagant. “It was as if they didn’t know what to do with their energy,” she says. “They were so careless with it.”

She also detects a certain rhythm to their visits. Her guests would at first fidget, then calm down, turn apprehensive, and express concern for wearing her out.

“I could also see that I was a reminder of all they feared: chance, uncertainty, loss, and the sharp edge of mortality,” she writes.

This slim volume could easily have turned cutesy, mawkish or worse. Bailey, who has suffered numerous and lengthy relapses for nearly two decades, could have sunk into self-pity — and who would blame her? She’s unfathomably ill, and horizontal, through much of the book’s journey.

That she wrote this elegant little gem is a triumph of empathy and determination over despair.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews for numerous publications.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story