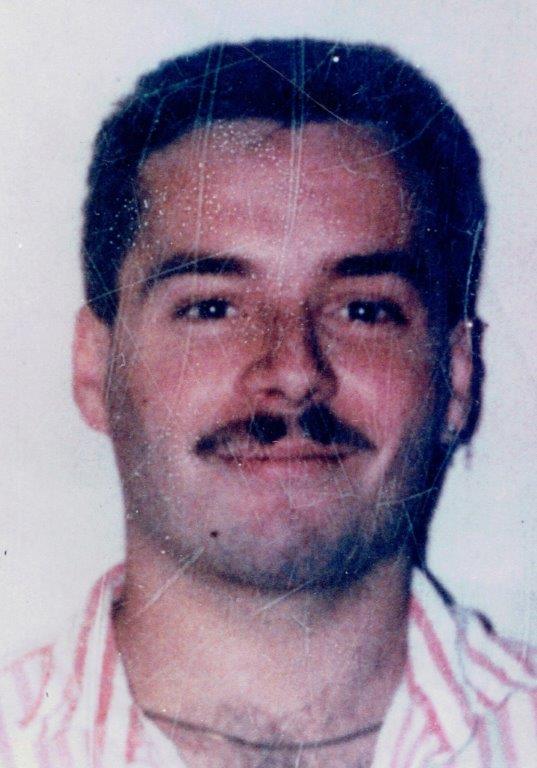

Thomas F. Napier was a talented young man with a gift for drawing and a lifetime of inner conflict.

A year ago, all that pain and potential was lost. Thomas Napier was found dead Feb. 20, 1994, in the Saco River.

State police have called Napier’s death suspicious, but they stop short of declaring it a homicide. Friends and family believe he was murdered. Others suggest he may have accidentally fallen into the water.

The state medical examiner’s office has officially ruled the cause of death as asphyxia by drowning.

“Why he wound up in the river is part of the investigation, ” said State Police Lt. Michael P. Harriman.

Napier’s friends and family believe the 22-year-old was murdered, possibly by someone who’d gotten into a fight with him.

Or, they speculate, he may have been killed because of his past involvement in the drug world. Maybe he knew something incriminating about someone, they say.

Whatever the case, Thomas Napier’s life ended on the brink of adulthood, leaving behind a puzzling trail.

HIS FINAL NIGHT

Napier was last seen alive Oct. 29, 1993, a rainy Halloween weekend night. It was Friday evening and Napier was ready to party.

After he got out of work at Cryo Industries in Sanford, he went to his grandparents’ home in Lyman, where he changed into a new pair of jeans and a pullover shirt.

He stopped by a buddy’s home nearby, then went to meet another friend with whom he set out for the evening.

With a pocketful of cash – about $400, including overtime pay from his shipping job – Napier met his childhood friend Rob Lang at Lang’s home about 8:30 p.m.

Taking two cars, they soon left Lyman and headed to a party in Biddeford.

On the way, they picked up a six-pack of Michelob Light and two Rolling Rock beers at the Five Points Mobil Mart in Biddeford.

About 10:30 p.m., Napier tried to coax Lang into going with him to another party in nearby Saco.

Lang declined because he had to work in the morning. Undaunted, Napier left by himself.

Napier didn’t say who would be in Saco. Those close to him say they never did find out whom he planned to see.

BODY FOUND

After two days, Irene Baker, Napier’s maternal grandmother, got worried. Her spirited grandson still had not come home, where he often stayed during the work week.

By Monday, his car, a 1984 Olds Cutlass, was discovered abandoned on Bradley Street in Saco. The windows had been rolled down and his prized stereo speakers were missing.

Napier’s parents believe they were stolen by his killer, or by someone who knows how he wound up in the Saco River.

State Police Lt. Harriman won’t say if police ever recovered the car speakers or what role they might play in the investigation.

By Wednesday, Nov. 3, nearly a week after he’d gone out partying, Napier was officially declared missing by the state police.

The following Friday, state police divers spent hours searching the Saco River in Biddeford and Saco.

Jim and Kathy Napier, the young man’s step-parents, kept an anxious vigil onshore, flanked by Lang and Mike Baker, Napier’s maternal grandfather.

Neither that daylong search nor a subsequent river dive on Jan. 6 proved successful.

Police never have explained why they looked to the river to find him.

But on Feb. 20, 1993, more than three months after he disappeared, he was found floating face down. An incinerator worker spotted him while patroling the plant’s grounds on the edge of the Saco.

“It still bothers me, ” said Eric Lagerstrom, who scans the river as part of his job at Maine Energy. “I think about it every day I’m working there.”

FAMILY CRITICAL OF POLICE

Over the past year, family and friends of Napier have grown frustrated by what they perceive as a lack of interest on the part of investigators.

“I’ll tell you this is a sick state when the police don’t want to do anything about it, ” said a bitter Baker, Napier’s grandfather.

Police dispute the family’s criticisms, saying they continue to follow up leads in the case.

“Our investigators have done some interviews on that in the last month and the case is still open, ” Harriman said.

Like others, Baker rejects suggestions that Napier may have accidentally fallen into the river.

CONVICTION, FRESH START

Family members say Napier had seen trouble before, especially after he graduated from Massabesic High School in 1990.

During that time, they say, when he’d been working for a paving company, Napier began taking drugs and getting into other trouble.

In October 1991, he burglarized a market in Bingham. He was convicted and served three months in jail in early 1992.

In jail, he realized he had to clean up his act, say family and friends.

From his cell, he often wrote to Lang, his friend, and sent him sketches with anti-drug messages and skulls and crosses.

Once released, he seemed ready to start fresh, with a new job, a new car and newfound determination.

“Tommy was turning his life around, ” said Jim Napier, his adoptive father. “He had gotten in with the wrong crowd before, but he had changed.”

Still, friends who knew Napier say while he seemed to have changed, he had a tendency to get into trouble when he consumed alcohol.

“He kind of had a big mouth when he drank, ” said Damien Joyce. Napier had stopped by his house before going out his final night with Lang.

Joyce believes that Napier may have offended someone at the party in Saco, unintentionally or otherwise, and that he was beaten up.

“If they hit him really hard, he might have passed out and whoever it was might have panicked, ” Joyce said.

But the medical examiner’s report found no evidence of bruises or other marks to indicate he was beaten.

A TROUBLED CHILDHOOD

Napier’s life was filled with conflict from early on.

After a failed adoption and stints in several foster homes, Napier was adopted by Jim and Kathy Napier when he was about 10.

He was so used to being bounced around, Kathy Napier said, that he was sometimes moody without even knowing why.

“Sometimes we’d have to hold him, physically hold him, and he’d struggle to get free. It was hard to get him to trust, even though he knew we loved him, ” she said.

In the few times that he would open up, she said, he would speak of one childhood disappointment after another. One time a foster home sent him to summer camp without telling him he would never come back.

LOSS OF TRUST

As a youngster living with the Napiers, he attended school in Wells for a year, until the family moved to the Massabesic school district, where he attended junior and senior highs.

He worked as a teen-ager in local restaurants, where he trained to be a cook.

Mark Thomas, owner of the Lucky Logger restaurant in Saco, recalls that Napier was usually quiet and his step-parents seemed strict.

“His parents were very protective. There were times when he would virtually lie to them to get freedom. Those are the things that stick out in my mind, ” Thomas said.

By the time he was a teen-ager, Napier had developed an ingrained distrust that found its way onto his sketch pads and journals.

Looking back, said Kathy Napier, it was clear that her stepson was someone with a talent that stemmed from his very soul.

His insecurity, she added, grew out of the experiences that started long before he became part of her family.

At about age 6, Napier and his sister Melissa were given away by their mother. Later, his first adoptive parents sent him packing on Christmas Day, and kept his sister.

The rejection, said Kathy Napier, compounded by stints in nearly a dozen foster homes, left the boy emotionally scarred.

“He was bounced around so much. He always had trouble trusting people after that, ” she said.

A SISTER’S MEMORIES

Melissa Titcomb, Napier’s biological sister, now lives in Florida. Until last week, she didn’t know her brother was dead. Family ties, she said, were nearly nonexistent.

“I knew they were looking for him, because I got a call from the Maine police, ” she said. “But I never knew they found him.”

Titcomb, 21, said the last time she heard from her brother was about three years ago. He had called in the spring and promised to meet her at a local Pizza Hut.

But he never showed up, she said, and she found no listing of him at the hotel where he said he was staying.

With only an occasional phone call or letter, the lack of contact was nothing new.

Still, she said, they’d always talked about trying to find their biological parents.

Now, she says, that familial dream will probably remain a fantasy.

“If I had known what happened, I would have come to his funeral. I didn’t know. God, I hope they find out what happened.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story