When Chris Grigsby and his wife, Kat Richman, think about how they want to live, they consider what type of world they want their 13-year-old son to grow up in.

“It’s important to think about those things, in regards to taking what you need and leaving the rest,” Grigsby said.

He says that ties in with his work at organic cooperatives and now as incoming director of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association Certification Services LLC. He and his wife both focus on saving energy and being sustainable, and when they decided to build a home, they chose an uncommon design for Maine: a straw bale house.

The idea to build such a house came from a walk more than a decade ago through the Common Ground Fair in Unity. The couple talked with Noah Wentworth, who represents the Evergreen Building Collaborative and had built about 10 straw bale buildings by then.

“We just got behind the concept of utilizing a natural resource for insulating a house,” Grigsby said.

One of the few downsides to choosing to use straw bales for the house was that construction took a little longer than he would have liked, Grigsby said, but they moved into their new home in Appleton by 2007.

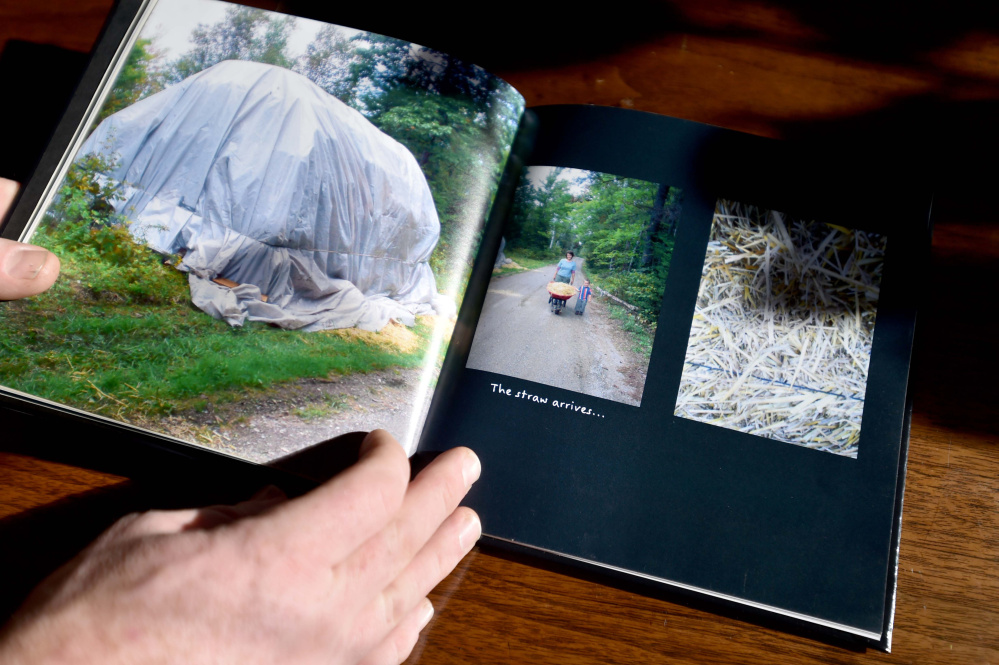

The home is like a traditional post-and-beam, two-story house, but it uses large, tightly compacted straw bales for insulation. The bales, bought from eastern Canada, are up to 4 feet long and cost the couple about $8 or less per bale, Grigsby said. While he couldn’t recall the exact number of bales they used, he said it was probably a few hundred. The total cost of the house was about the same it would have been if they had used a completely traditional model, he said.

There are many positives to building a house using straw bales, Grigsby said, and, for him, few negatives.

While a house made with straw would seem a likely fire hazard, the straw bales are actually fire-retardant. The bales are packed so densely that there is not enough oxygen to keep a fire alive should it come near the house, Grigsby said. The fire would smolder when it reached the house, causing some damage but dying out.

Builders also use straw over hay because it has no protein or nutrient value, so it doesn’t attract mice or rodents.

Some insurance companies don’t cover straw bale structures, but the couple didn’t run into that situation. They got a construction loan through Wells Fargo without a problem, as well, he said.

PUT BACK WHAT YOU TAKE

Grigsby works at Crown O’ Maine Organic Cooperative as the director of operations, which distributes locally grown produce to clubs, restaurants and retail stores across Maine, but he will be leaving soon to join MOFGA.

On Nov. 3, it was announced that he would be the new director of MOFGA Certification Services LLC., an offshoot of the organic advocacy nonprofit focused on supporting farmers. MOFGA Certification Services certifies farms as organic and has about 520 client operations.

Grigsy has been on the organization’s certification services management committee, which oversees the business that certifies farms as organic, for the past two years. He is stepping down with the announcement of his new position.

As director of the certifying arm of MOFGA, Grigsby will serve as a point of communication between the LLC and the nonprofit organization.

“There’s been a big sort of uptick in farmers wanting to (become organic),” he said, accrediting much of that to MOFGA’s role in supporting farmers and helping them through the process.

The work that MOFGA does is about much more than farming, and the ethos of being organic influences how he tries to live, Grigsby said.

“Part of being a certified organic farmer is you have to have a farm plan,” he said, explaining that organic farmers have to write how they are going to put the nutrients they take from the soil back into it.

His straw bale home’s walls are at least 18 inches thick and create a “thermal mass” protecting the inside of the home from the weather outside.

The couple use a wood stove as their sole heating source. In the winter, Grigsby said, it can be 68 degrees inside without heat and, after a cold night, they can wake up to a 64-degree house.

Similarly, the house never gets above 75 degrees in the summertime.

The couple also bought energy-efficient appliances and a solar hot water heater, which collects solar energy to heat up water so the boiler tank doesn’t have to work as hard.

“We were willing to invest a little bit upfront to save in our utility bills,” Grigsby said. Now they spend about $40 monthly on electricity.

They also created a homestead, living out the idea that people should try to make what they can at home.

While he and his wife both work full time and lead busy lives, they do what they can to be self-sufficient. They grow blueberries, have a 40-by-40-foot garden and raise chickens for their eggs.

“My work and career is really a lot around local food,” Grigsby said. “What’s the most local food you can have? It’s coming out of your garden.”

A LITTLE BIT DIFFERENTLY

When Grigsby and his wife started looking at building a home and saw what they could save with a straw bale house, they thought, “That makes a lot of sense,” he said.

But it’s difficult to find how many other people have thought the same thing. The International Straw Bale Building Registry collects data about straw bale construction all over the world, but it says its numbers are probably inaccurate because builders and owners list the buildings on a voluntary basis. Actual numbers are probably 10 times more than what has been reported to the registry, its website says.

According to the registry, there are 778 straw bale buildings in the United States, nine of which are in Maine, though Grigsby’s home isn’t listed among them.

Straw bale homes date back to the Paleolithic era in Africa and up to 400 years ago in Germany. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, people in the Nebraska Sandhills started using straw bales to build because of a lack of other building materials.

Grigsby said while the style isn’t popular in Maine, a lot of homes in the Southwest were constructed with straw bales.

He hopes the choices he and his wife have made about their lifestyle will serve as an example for at least his son, he said.

“There are different ways to live a comfortable life,” he said. “We can live a little bit differently and we can have a little less impact on the environment … if we can all sort of have a little bit of an understanding on what the impact is.”

Grigsby said he understands that life is hectic, and there are days he’ll come home from work and just heat up mac and cheese for his son before soccer practice, but for the most part he tries to “lead by example.”

“There’s a movement there that I don’t think is a fluke or any kind of a one-off, at least not in Maine,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story