In the 1970s organic gardening was something done by a few back-to-the-landers and other free spirits who also favored marijuana over beer.

Now in 2015, “Them is us.” In the intervening years, science has established that the best way to grow healthy and plentiful vegetables is to create healthy soil to support them. Add to that, it’s probably smart to avoid ingesting chemicals that are capable of killing other living organisms even if science has shown that those chemicals, if used according to instructions, do not kill people.

Put these facts together and you may be ready to convert your conventional vegetable garden to an organic one. Not a moment to waste as it’s mid April, when Mainers typically plant, transplant and improve (“amend” in gardenerspeak) soils. To make the conversion, you don’t need to get your garden certified by the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association. In my opinion, respectfully, such certification would be a waste of paper and effort. You’re taking your kitchen garden to organic production because it’s good for you and your environment (certification is useful if you want to sell your organic vegetables). The process will take a few years, but that’s OK. Gardens are never completed. The idea is to enjoy the journey, and the process of turning your garden to organic is fun. Here are 10 keys to the task.

The organic gardener’s adage is “Feed the soil, not the plants.”

The food for soil is carbon, and its favorite dish, so to speak, is compost, although chopped-up leaves, leaf mold and other plant material also work. The bacteria, fungi, nematodes, worms and other living things in the soil that your vegetables need in order to grow will eat that carbon. Ideally, the compost comes from your own compost bins, where you’ve dumped table scraps, leaves, pulled weeds, spent flowers and the inedible parts of your garden vegetables. If you don’t have compost bins, start them. Until those bins start producing compost, buy compost in bulk, by the truckload, delivered if you don’t have your own truck. Bulk compost will be less expensive and more sustainable than hauling plastic bags of compost home from the garden center; almost all garden centers sell it, charging about $35 to $50 a yard.

Organic gardeners have problems with plastic. It’s made from oil and it will never rot. But floating row cover is one plastic product in which the good outweighs the bad. “Think of row covers first when seeking pest protection,” the Fedco catalog advises. “Protects crops from flea beetles, cabbage worms, potato beetles, leafhoppers, even woodchucks.”

Row covers hold off chilly air as well as pests, yet they let the rain penetrate. By using row covers to ward off assorted hoppers and beetles, you can avoid applying pesticides. In addition, the covers provide warmth, which means your garden will produce more vegetables. Handle the row cover carefully – dry it thoroughly before you roll it up and put it away for the winter – and you should be able to use it for years.

Soil test kits

The only way to find out what’s in your garden is a soil test. “If you don’t test, you’re just guessing,” Barbara Murphy, an extension educator based in South Paris, says in an instructional video on the website for the Analytical Laboratory and Maine Soil Testing Service, located in Orono.

Most gardeners get a soil test when they begin a garden and never do it again, although they should do a new soil test every few years. If you are switching from a conventional to an organic garden, you want to know what products – compost, lime, greensand or others – will help make the transition seamless.

Soil test kits are available at your local cooperative extension office or you can order them at the testing service website, anlab.umesci.maine.edu. The test costs $15.

Whenever possible, keep your crops off the ground. If a vegetable has even the slightest tendency to climb, encourage it. More air will circulate around cucumbers, squash, peas, beans, tomatoes and melons that climb up fences, frames or cages. The circulating air helps keep them dry, resulting in less mildew, blight and other fungal diseases.

While plants feed on the soil, they get their energy from the sun, and they get more sun if they are raised above the soil. Crops like beans and peas like to grow on fences. Cucumbers, squash and melons prefer supports and about a 45-degree angle to the ground, although fences will work. With tomatoes, avoid the conical wire supports that are sold in hardware stores. A solid square or round cage supports the fruit and branches better and stands up to the wind. If you buy carefully, you may find cages that unlatch and fold flat for winter storage. Those are the best.

We Mainers are lucky. We are nicer than most other people. We have superb scenery and plentiful seafood. We also have adequate rainfall.

Even so, rain barrels make sense. During hard rains, soil erodes, costing gardeners precious topsoil. In addition, the rain picks up spilled gasoline, fertilizer and other pollutants, which then are carried into nearby bodies of water. When you use water from a rain barrel after the storm stops, the water goes into the ground, where it belongs, rather than running off.

Finally, even though we have plenty of water, why pay for it if you don’t have to? And having a rain barrel near your garden is more convenient than hauling or hosing water from a tap. The Portland Water District sells 55-gallon rain barrels for $63.50, with an ordering deadline of April 24; go to pwd.org. My wife Nancy and I have three, two of which are connected to a downspout on our patio. I use watering cans and water all the patio plants from those barrels. The third barrel gathers the water from our shed, in our vegetable garden. There I use my watering cans when I’m trying to get transplants going in the spring.

A rototiller is an organic gardener’s enemy – and not just because it is difficult to keep running. Running a heavy piece of equipment through the garden compacts the soil, and pushing steel blades 6 inches deep into the ground destroys the structure of the soil.

Organic gardeners are split on ways to avoid the power tiller. No-till gardeners create a layer of organic material above the soil and plant their seeds and transplants right below that. They believe any turning of the soil brings weed seeds to the surface, which lets them sprout.

I still prefer loosened soil, and I get it with a broadfork or U-Bar – a huge 5-foot-tall tool with a number of (6-inch) tines. The gardener steps on it to drive it into the ground and pulls back on the upright handles, just barely turning the soil – which is still sound but a little loose. The rhythmic exercise of working the broadfork down the length of the garden is my favorite spring dance.

Non-GMO seed

Genetically modified seeds are not allowed in gardens that are certified organic. The four major seed providers in Maine – Fedco, Johnny’s Selected Seeds, Pinetree Garden Seeds and Allen, Sterling & Lothrop – have all taken the safe-seed pledge, saying that they “do not knowingly buy, sell or trade genetically engineered seeds or plants.” Another good reason to buy local.

Avoiding plants that are created in a laboratory does not mean you are stuck with old-fashioned varieties. Hybrids, created by cross-pollination, are acceptable and being introduced every year. But do avoid the GMOs.

You will plant your vegetable garden over two months – even longer, if you practice succession planting. Onions, spinach and peas can go in now, and you keep planting until June, when you get to heat-loving plants like cucumbers and tomatoes. If you don’t have a plan, you might run out of garden space before you’ve planted everything.

A garden plan also can increase efficiency. The typical garden with rows of crops is designed to be tended by horse-drawn or power equipment. Since you will provide your garden’s power, you can abandon the rows. It is more efficient to use a type of square-foot gardening, planting more densely in rectangles that are 3 to 4 feet wide, depending on the length of your arm and how easily you can reach the center of the plot. Put mulch or straw in the areas around those plots, so you know where to walk.

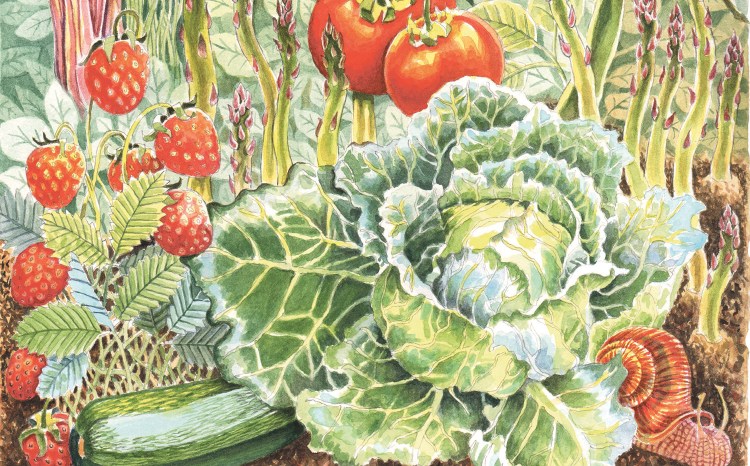

It is wonderful to get free food that you don’t have to plant. Perennial crops are a key to permaculture, which is – to put it very simply – organic gardening taken to the next level. You put these plants in once, and you get food for decades. Some of my favorites are asparagus, rhubarb, strawberries and raspberries, but there are plenty of others – including even fruit trees. This is the lowest-impact type of food production, both in terms of material and human endeavor.

Gardening gloves are personal. No one can advise anyone else on the best type of glove to use. I prefer close-fitting elasticized gloves for routine work, because I can pick things up easily, and leather gloves for when I am dealing with thorns and other items that can scratch.

But you need gloves, not only to protect your hands from scratches. You also have to protect your mind from the yech factor when picking insects such as Japanese beetles, lily leaf beetles and Colorado potato beetles from your crops (because remember, you’re giving up pesticides). Yes, in small gardens hand-picking works, and you are more likely to do it if you can avoid skin-to-bug contact.

Tom Atwell has been writing the Maine Gardener column since 2004. He is a freelance writer gardening in Cape Elizabeth and can be contacted at 767-2297 or at:

tomatwell@me.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story