Chris Sauer was speaking at a 2007 energy conference in Anchorage, Alaska, about his ambitions to test a marine power generator in the massive tides of Cook Inlet when a participant asked if the design could be downsized for rivers. That turned out to be a prescient question for Sauer, president of Portland-based Ocean Renewable Power Co.

Mainers who have heard of Ocean Renewable Power Co. know it as the innovative startup that built North America’s first grid-connected tidal generator in the waters off Eastport in 2012. But as Sauer has determined, the company’s financial future actually may lie in selling off-the-shelf current generators for remote, off-the-grid communities that are located next to fast-moving rivers.

A pilot project in Alaska this summer will test not only the company’s RivGen technology, but also its ability to attract investment capital that’s critical to moving the business forward. Sauer figures the company needs $15 million to $20 million over the coming three years to take the next steps in marine power and get its river units on the market. He is hopeful that revenue from RivGen could finally put the 10-year-old company in the black.

“We think RivGen could be our nearest-term profit potential,” he said.

Harnessing the power of the tides has received the most public attention, and the larger size of the units does hold more promise for total megawatts of electricity generation. But places on the planet with big tidal ranges, such as those found in Maine’s Cobscook Bay, Nova Scotia’s Minas Basin and Alaska’s Cook Inlet, are limited. In contrast, Sauer discovered that hundreds of millions of people who either don’t have reliable electricity or pay a lot for it, live close to flowing rivers.

“Rivers are everywhere in the world,” he said. “So in that sense, it’s a much bigger market.”

That reality is leading the company to create a separate business arm to develop and market its patented RivGen units. It is working now with partners in Chile, Alaska and Canada’s Northwest Territories. The idea is to sell standard-sized units – “think of it as an expensive Honda generator,” Sauer said – that will be fabricated nearby and installed by local companies. Technology that can tap this current potential is known as hydrokinetic, to differentiate it from conventional, fixed-in-place hydroelectric dams.

“There will still be significant revenues coming back to Maine,” Sauer said, “but we see a half-dozen places around the world where these will be built.”

Alaska is a likely candidate.

More than 81,000 people live in 190 communities in Alaska that are off the main power grid and received a total of $39.7 million in public subsidies, according to the Alaska Energy Authority. That’s because their power is largely generated by diesel fuel brought in by airplane or barge and is expensive.

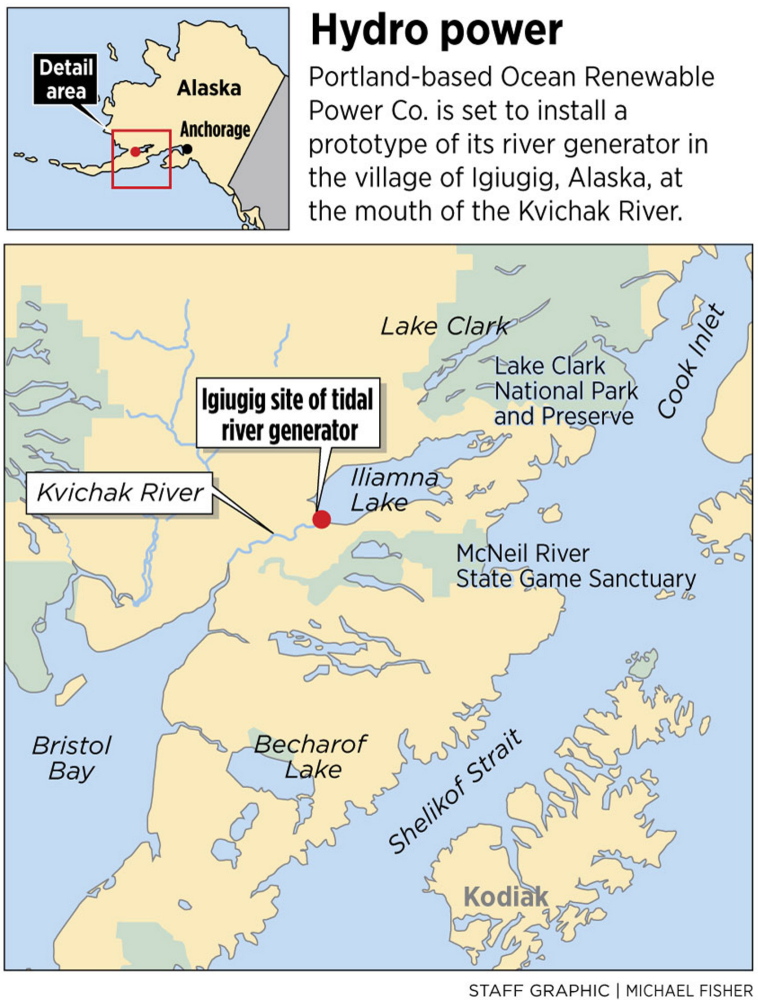

A prime example is the village of Igiugig, which is located at the mouth of the Kvichak River in southwest Alaska. The 69 residents, mostly Yup’ik Eskimos, Aleuts and Athabascan Indians, fish and hunt and in summer host visitors in a popular sportsfishing destination for sockeye salmon.

But keeping the lights and heat on is costly and complicated. The village spent $221,240 on 28,401 gallons of diesel fuel last year, or $7.79 a gallon, according to the Igiugig Village Council. For electricity, that translated into 80 cents per kilowatt hour for homes, more than five times what a Maine homeowner pays. The fuel was transported by plane in 2,000-gallon loads. A barge tops up the tank farm, if the river is high enough in the fall.

That’s why Igiugig is partnering with Sauer’s company to test a small RivGen unit for several months this summer. It will be the first commercial-scale test of the unit.

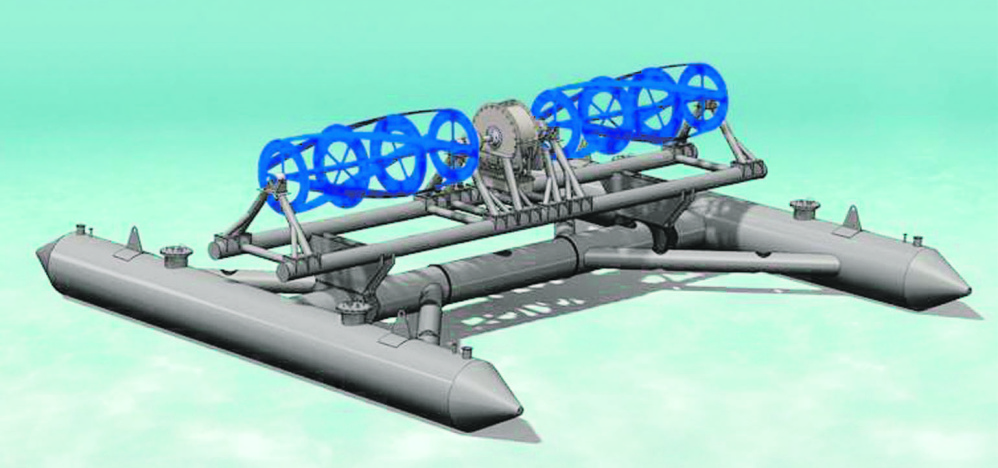

The 34-foot-long machine has two turbines that spin in the current and are connected through a single driveline. It is held in place on the river by anchor lines and submerged, ballasted pontoons.

The unit will have a generation capacity of 25 kilowatts when the current is moving at 6.75 feet per second. That could produce half the village’s electric needs, about 25 homes, according to estimates.

“If this technology proves itself and can cut electricity costs in half, it will be a huge benefit to the commercial and public users,” said AlexAnna Salmon, president of the village’s Tribal Council. “It will make living in remote Alaska much more affordable. It will also be better for the environment.”

Salmon said the biggest challenges she sees is installing and removing the device and integrating it in the diesel powerhouse. If the technology works and becomes commercially available, the village would want to raise money to buy one.

Sauer said the 25-kilowatt unit will retail for $500,000. The company also expects to produce 10-kilowatt and 50-kilowatt models.

Alaska has more than 50 communities similar to Igiugig that are on large, powerful rivers that could displace some diesel fuel with river power, according to Chris Rose, executive director of the Renewable Energy Alaska Project, an Anchorage-based coalition that promotes renewable power alternatives. A primary obstacle for river current projects, he said, is diverting logs and other debris that are common in many Alaskan rivers.

“What might be a mere pilot project in the Lower 48, where power prices are much lower, could be a significant economic boom to a community in Alaska,” he said.

Sauer’s company also faces challenges from competition for investment and grant funds. The company, which now has 24 employees, has existed largely through $18 million in federal grants and an undisclosed amount of money from a private equity firm.

Other companies also want to bring their technologies to a commercial scale and sell or build tidal and hydrokinetic devices. Perhaps the best known in the United States is Verdant Power LLC, which is working on its Roosevelt Island Tidal Energy Project in New York City’s East River.

But Sauer said overseas firms with deep-pocket parent companies pose more of a threat. They include Irish startup OpenHydro Group Ltd., which now is part of DCNS, the French defense and energy company. OpenHydro announced last month that it has partnered with Emera Inc., the Nova Scotia energy firm that owns utilities in northern and eastern Maine, to deploy a grid-connected tidal project in the Bay of Fundy next year that could power 1,000 homes.

“On a global basis, it’s getting more competitive,” said Sean O’Neill, president of the Ocean Renewable Energy Coalition, a trade group with members that include Verdant and Ocean Renewable. “Companies are going to Scotland, Ireland, Portugal and Canada because they have incentives that we don’t have.”

But O’Neill said the company’s management team has done a good job of attracting money and forming productive community relations with local project sites, such as those in eastern Maine and Alaska.

“What we need now is more run-time in the water,” he said. “Investors are dealing with a lot of fear of the unknown. These technologies haven’t been deployed in the United States and we need to get them in the water to see what the effects are, positive and negative.”

Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story