SACO – When the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers designed and built the first portion of a jetty at the mouth of the Saco River more than a century ago, the idea was to open the waterway to more commercial shipping and ease navigation in one of the longest rivers in New England.

The jetty, begun in the early 19th century but not substantially in place until 1911, was designed to steer sand and sediment from the mouth of the river farther out into Saco Bay. Widening and deepening the river and stabilizing its confluence with the sea, engineers thought, would enable ships to travel upstream to what in 1825 was the largest textile mill in the nation, promoting commerce for the cities of Saco and Biddeford.

All this made the jetty seem like a good idea at the time, said Patrick Fox, director of Saco’s Public Works Department. But the jetty no longer seems to be the solution it once represented; in fact, it has become a very expensive and controversial problem.

The jetty has altered the dynamics of wave action, currents and sand drift, subjecting Camp Ellis to punishing forces during storms and extremely high tides. The beach has eroded over time, and streets and houses have washed into the sea, causing millions of dollars in damage to public and private property.

Climate change, and its impact on rising sea levels and extreme weather conditions, threatens to exacerbate the Camp Ellis situation.

The complex ocean forces — along with the inadvertent impact of the jetty — have confounded every attempt to make lasting improvements to the river, its mouth and nearby coastal communities.

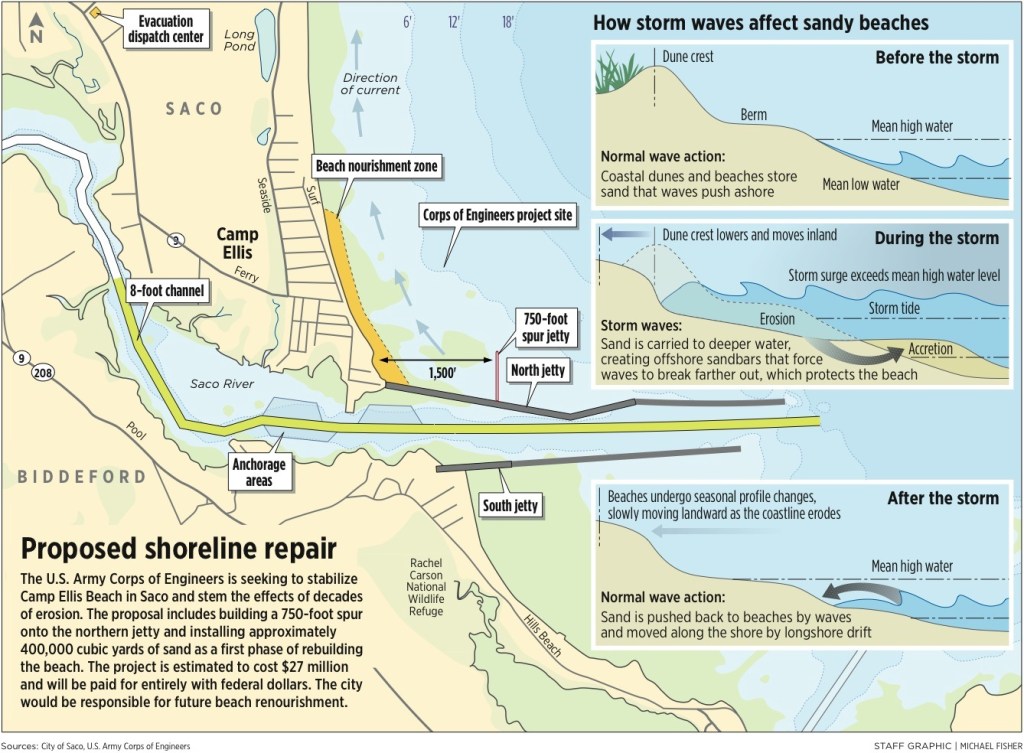

Now the Army Corps of Engineers is poised to embark on a $27 million plan to address the problems, which the corps itself acknowledges were caused, in part, by the jetty it built a century ago.

“The intent was 100 percent navigation of the river,” said Richard Heidebrecht, the corp’s project manager in New England. “But inlets move, and this particular one has moved north and south. … The Camp Ellis beach shoreline has shown continued erosion since the early 1900s. We have a problem that we have some responsibility to correct.”

The plan, selected after nearly 15 years of study and more than 35 proposals, is to install a 750-foot spur onto the northern arm of the jetty, about 1,500 feet out and roughly parallel to shore. The project would also reinforce about 400 feet of the existing jetty and replace 400,000 cubic yards of sand to the beach directly to the north. It is, said Heidebrecht, the best shot Camp Ellis and the surrounding section of the southern Maine shoreline have of staying intact — more or less.

But even when the spur is in place, massive amounts of sand will have to be replenished at the Camp Ellis shoreline — not just once but every three to 10 years.

“It’s an enormous amount of sand, the equivalent of a dump truck load delivered every six minutes for 90 days during the off-season,” said Patrick Fox, director of the Saco Department of Public Works. That much sand carries a hefty price tag, as much as $3 million from the city’s budget each time the replenishment is done, according to the Maine Geological Survey and other coastal experts.

Just how long any round of beach-sand replacement will last, no one can say. “It’s the most permanent solution available to us now,” Fox said. “It won’t be permanent in (the sense) that it’ll be fixed forever. It will always require maintenance; it will always require funding.”

The city is waiting now for a draft partnership agreement with the corps, outlining exactly what costs it would have to bear for beach replenishment beyond the initial project. That agreement must be completed before the project can move ahead.

“We’ve never gotten this far,” said Rick Milliard of Saco, vice chairman of the Saco Bay Implementation Committee. Both Milliard and his father have been working for 15 years to get the Camp Ellis situation resolved. “It’s progressing, but slowly,” Millard said.

Richard Michaud, Saco’s city administrator, said Saco and Biddeford are considering whether to jointly purchase a dredge, at an estimated cost of about $600,000, to periodically dredge the mouth of the Saco River and use the sand to replenish Camp Ellis and another beach in Biddeford.

Michaud said Gov. Paul LePage is expected to visit Camp Ellis later this month. The city may ask the state to help fund the beach replenishment program.

Michaud said city officials likely won’t take up a proposed agreement with the Corps of Engineers before November.

Meanwhile, in the past year alone, parts of Camp Ellis have lost a swath of beach as wide as 25 feet in spots, residents have said.

Huot’s Seafood Restaurant in Camp Ellis is one of two eateries that attract tourists to the area. It has felt the effect of erosion this year for the first time, said Denise Gelinas, who runs the family-owned establishment with her husband, Gerry. In the past, the encroaching water was a slightly more distant problem, but this year, rising water and receding beach meant Huot’s faced flooding twice, with soaked carpeting that had to be cleaned and dried.

“It’s really hitting home,” said Gelinas, whose family has owned Huot’s since 1935.

“There are some people who are right on the edge,” she said. “For me, it’s our livelihood; we have 60 employees. With the waves and the sea — I just don’t trust it. And it’s only going to get worse.”

MULTIPLE FACTORS AT WORK

Like most residents and business owners in Camp Ellis — which provides about 30 percent of the city’s tax base — Gelinas supports the jetty spur plan and wants to see it done as soon as possible.

“What are we going to be in three years?” Gelinas asked. “Are we going to be waterfront?”

That might depend on how a lot of complicated factors play out.

“There are a lot of things happening there,” said Robert Marvinney, state geologist and director of the Maine Geological Survey. “The mouth of a major river and a bay is always a dynamic environment.”

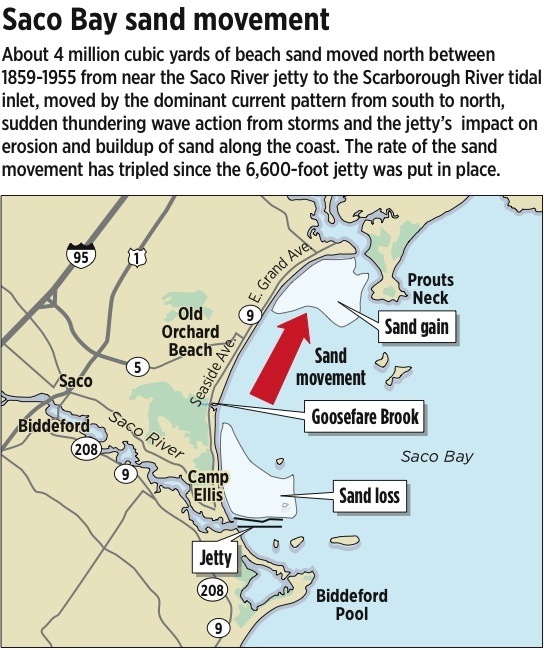

The sand movement is controlled by opposing wave and river forces, said marine geologist Peter Slovinsky of the Maine Geological Survey. The dominant sediment movement in Saco Bay is south to north. Most of the sand that originally built and sustained the beach at Camp Ellis came down the Saco River. The jetty now drives that sand supply far out to sea and very little makes its way back to naturally rebuild the Camp Ellis beach. Without this supply, the incessant south-to-north movement of sand robs the Camp Ellis beach and adds it to beaches to the north.

It bypasses the shoreline at Camp Ellis and nearby Ferry Beach and is washed farther north, sometimes emptying on Old Orchard Beach. Over time, it is pressed onward to even more distant beaches, including Prouts Neck in Scarborough.

And when dominant near-shore currents are coupled with opposing prevailing currents farther out, a continual swirl of sand back and forth occurs along this long stretch of open dune beach.

The effect is a constant here-today-gone-tomorrow sculpting and shaping of the sandy beach that extends for miles toward Old Orchard Beach and Scarborough.

But at Camp Ellis, additional stresses arise from different types of wave energy, too. Sand is not just moved north; the beach is virtually excavated as storms — often out of the north — drive waves along the jetty in a drilling effect.

In addition, small islands and shoals off Camp Ellis focus waves right on the beach next to the jetty. Situated as the shoreline and jetty are, there is a funneling effect of the storm waves, building power in the moving water that erodes the beach and dunes. This back-and-forth action at the southern end of Saco Bay leads to a net movement of sand to the north.

Some waves generate friction as they race along the jetty, while others are reflected, rebounding when they hit the jetty, bouncing back off and then toward shore. The end result is that the beach, already under assault, is raked twice, Slovinsky said.

On a good day, these forces conspire to gnaw away at the sand, hauling it back into the water and sending it swirling north. But during nor’easters — particularly winter storms — the wave energy is greatly intensified, whipping it into an explosive force, geologists said.

That effect became especially pronounced during a 1978 storm that followed earlier jetty modifications. As many as 18 houses came down in that one storm, said Dean Coniaris, an optician and lobsterman whose home overlooks the beach. Within a decade the destruction on the beach mirrored the changes to the jetty and the flattening of the stone, he said.

But the common denominator of all these destructive pressures — and their solutions — is the jetty. “They created the perfect structure to cause beach erosion to Camp Ellis,” Slovinsky said.

SOMETHING HAS TO BE DONE

The coastal community has been disappearing at the rate of several feet of beach per year, two or three cottages annually, several streets over the last half-century — victims of the one constant in this ever-changing scene: erosion. Between 30 and 50 cottages, homes and other buildings and millions of dollars of infrastructure have been destroyed by erosion since the 1960s. Geologists, engineers and marine experts have conducted a host of studies that project the damage will continue unless dramatic changes are made to the sandscape and what lies nearby.

“There is simply no more land to give without more homes toppling into the sea or people having to leave or move their homes,” Saco resident Charlie Reade has warned.

If the full project funding gets the green light, federal money will cover the initial costs — the spur and the first round of sand replenishment. But the city of Saco is on the hook for the ongoing sand maintenance job, estimated at between 365,000 and 400,000 cubic yards at a time, as needed. It remains to be seen whether city residents will accept that continuing cost, not to mention the heavy truck traffic during the time of the year many cherish for its quiet.

“We may find there is opposition to that,” said Fox, the city’s public works director.

The project’s estimated cost remains a source of concern and controversy, in part because no one — including the corps — believes the jetty spur and beach restoration can stop the sea or halt the erosion completely. The best-case scenario, all experts have said, is that erosion will be slowed.

But something has to be done, residents and city officials agree.

Right now, the significant sand loss at Camp Ellis occurs mainly along 2,000 feet of its coastline each year. The Saco Public Works Department performs sand dune and roadway replacement from erosion 10 to 15 times a year, already allocating more than 750 man-hours a year to the work.

Meanwhile, pummeling waves, high winds, nor’easters, blizzards and drifting sand are predicted to keep on doing what they have done right along, namely, sabotaging the best-laid plans for the Saco River and the parts of the neighborhood near its mouth and now, northward to Ferry Beach State Park.

Even Biddeford, Old Orchard Beach and Scarborough are seeing evidence of the movement of sand from south to north, said Millard. “It is a very difficult engineering problem,” he said.

If the river had not been altered, Camp Ellis might have survived with little incident, or even grown in sand mass, but Saco and Biddeford would have lost crucial manufacturing development. Had the jetty never been built, the beach north of the river’s mouth likely would have been replenished and rebuilt naturally. Even the sand pulled off the beach and out into deeper water in winter storms would be returned in spring, geologists have said.

But the jetty has changed the river, bay and shoreline so profoundly over the decades that removing it — which to some people is the obvious answer — would fail to return the area to its original condition.

“The system is so out of balance that if they did that, the corner of Camp Ellis would be lost,” said Marvinney, the geologist chairman of the Saco Bay Implementation Team. “The spur will break up the worst of the wave action and the current that runs along the jetty,” he said.

CLIMATE CHANGE A BIG UNKNOWN

And now, another, bigger manmade problem looms. Projections from the corps of engineers and geologists suggest that human-induced climate change resulting in rising sea levels and more extreme weather could make matters exponentially worse for Camp Ellis. Depending on the extent and severity of rising sea levels, the reach of the ocean could extend inland by about the depth of the lots of five to seven properties along the shoreline of the community.

And whether the jetty spur would be drowned in the process is enough of a worry to have spurred the suggestion the project proposal be revised to add a few more feet to the height of the spur or to add more sand to increase dune height.

“The coast is tough,” said the corps’ Heidebrecht, acknowledging that if climate change results in huge rates of sea-level rise, “all bets are off.’

“How many bad storms are you going to get in the next five years?” he said.

“But I believe we have the appropriate solution,” Heidebrecht said. The spur will result in conditions that will come close to pre-jetty conditions, he said. “We definitely hope it will go ahead.”

Whatever happens here will be watched with interest all along southern coastal Maine, because Saco is not alone in facing these uncertainties, geologists have said. Many other communities and beaches, including Kennebunkport, Wells Beach and Popham Beach, already face similar threats.

What is still unfolding in Saco could have far-reaching implications for other coastal areas faced with ongoing erosion, more intense storms and rising sea levels due to climate change-in short, a shoreline that simply won’t stay put.

North Cairn can be contacted at 791-6325 or at:

ncairn@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story