Long before Mitt Romney became the millionaire candidate from Massachusetts, he was his father’s son, weeding the garden in the upscale suburb of Detroit where he grew up. He hated the chore. But he idolized the man who made him do it — George Romney, the outspoken, no-nonsense, auto executive turned politician.

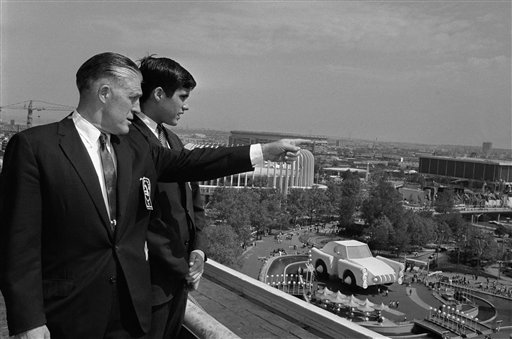

Romney shares an uncanny physical resemblance to his father, with the same graying temples and square jaw. And their lives have followed strikingly similar paths. As young men, both spent time abroad as Mormon missionaries and then passionately pursued the women they would marry. Both were successful businessmen who made personal fortunes before moving into politics. Both were church leaders, governors and aspiring presidential candidates.

Romney frequently invokes the memory of his father on the campaign trail. Photographs of George Romney adorn his campaign bus and headquarters in Boston.

“If people understood that equation of George Romney and his impact on my life and on Mitt’s life, they wouldn’t be so curious about why Mitt is running for president,” Romney’s wife, Ann, said in 2007, when her husband first sought the presidency. “He is why Mitt is running.”

The biggest difference between father and son? Personality.

George Romney was a garrulous, engaging, shoot-from-the-hip politician who stuck to his principles and said what he believed — to his political peril. With his 17-year-old son by his side, he stalked out of the 1964 Republican convention after trying unsuccessfully to promote a plank in the party platform denouncing extremism. In 1967, he was drummed out of presidential politics after saying he had been “brainwashed” by American generals into supporting the Vietnam War while touring Southeast Asia two years earlier.

Romney’s candidacy — he was then a leading contender for the 1968 Republican presidential nomination — never recovered.

His son never forgot.

“It did tell me you have to be very, very careful in your choice of words,” he said in 2005. “The careful selection of words is something I’m more attuned to because Dad fell into that quagmire.”

Critics say the father who railed against conservative extremism would hardly recognize the son’s accommodations to those on the right. Or his complete reversal on key issues — abortion, gun control, tax pledges and gay rights — that leave even some supporters scratching their heads about Romney’s core beliefs.

“Multiple Choice Mitt,” Edward M. Kennedy famously dubbed Romney during their 1994 U.S. Senate race in Massachusetts, a charge that still echoes.

Romney doesn’t attempt to explain the changes, other than to say he has “evolved” on issues.

“I’m as consistent as human beings can be,” he told a New Hampshire editorial board last year.

FAR FROM AN OPEN BOOK

Speaking to the NAACP in July, Mitt Romney said blacks would vote for him if they “understood who I truly am in my heart.” That’s a dubious assertion — his opponent is Barack Obama, after all — but it does raise the question: What is in Mitt Romney’s heart?

Friends and family testify to his fine impulses, but those who do not know him well must see past his stiff, sometimes painstakingly scripted responses. They must look for patterns in his political zigzags, and try to account for his extraordinary ambition. Unavailable and unrevealing, the candidate is far from an open book.

But some of the influences that helped make Romney the man he is are apparent. His father, for one. And the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which, for believers, is considered as much a way of life as it is a religion. Romney, who rarely talks about his faith in public, grew up steeped in the Mormon tradition, which emphasizes family, service, industriousness, tenaciousness and humility.

There is no paid hierarchy in the Mormon faith and male church members serve as lay leaders. Romney spent about 14 years as a bishop and stake president, an ecclesiastical leader who oversaw a dozen congregations and thousands of worshippers in New England. Though he had a demanding business career and was raising five boys, Romney devoted up to 25 hours a week to church duties — giving sermons, visiting the sick and counseling members about everything from work to marriage. He once described himself as a “true-blue through and through” believer, though he has taken pains to declare that the teachings of the church would not influence his obligations as president.

“To understand Mitt Romney,” says Ronald Scott, a distant cousin who wrote a biography of the candidate, “you cannot underestimate the influence of his father, or the importance of Mormonism in shaping his life.”

Willard Mitt Romney was considered something of a miracle baby by his parents, born in 1947 after a difficult pregnancy. The youngest of four, he was raised in the affluent Bloomfield Hills section of Detroit, where his father was CEO of the now-defunct American Motors Corp., before becoming governor of Michigan. His mother, Lenore, later was an unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate.

Enrolled at the elite Cranbrook School, Romney was a mediocre student and a poor athlete, best known for his love of practical jokes. Former classmates remember him dressing as a police officer and tapping on the car windows of teenage friends on dates. He once staged an elaborate formal dinner on the median of a busy street.

His prankster reputation was depicted in a darker light in a recent Washington Post article, which described how he and others taunted a gay student, pinning him down and cutting off his long hair. Romney says he doesn’t remember the incident and apologized if his youthful “high jinks” offended anyone.

“He wasn’t a standout, but there was definitely something special about him,” says Eric Muirhead, then captain of the school’s cross-country team, who describes a race in which Romney stumbled over and over. Clearly struggling, his teammates tried to help him, but he angrily waved them away. Though Romney finished dead last, the crowd gave him a standing ovation.

To this day, Muirhead says, he has never witnessed such determination.

In his senior year, Romney began dating his future wife, Ann Davies, who attended a sister school to Cranbrook. The young Romney was so smitten that, when he went to France for two and a half years as a Mormon missionary, his father took the young woman under his wing and introduced her to the church. The elder Romney eventually baptized her in the faith.

France was a tough challenge for a clean-cut young American trying to convert wine-loving Catholics to a religion that eschews alcohol, and Romney has talked about the humiliation of having door after door slammed in his face.

But it was in France that he first emerged as a leader. When a devastating car crash killed the wife of the mission president, Romney, who was behind the wheel when another car slammed into his, went on to head the mission after recovering from his injuries.

Former classmate and friend Jim Bailey said that when Romney returned to the U.S. he was noticeably more mature and far more disciplined in his studies.

“It was a life-changing experience and he learned a huge amount,” Bailey said.

After graduating from Brigham Young University in 1971, Romney earned dual law and business degrees from Harvard. He headed straight into the business world, joining the Boston Consulting Group, and then Bain & Co., another Boston-based consulting organization. In 1984 he was picked to head its spinoff, Bain Capital, a private equity firm that bought and restructured companies.

CALCULATING RISK-TAKER

At Bain, where he spent a total of 15 years, Romney was known as a tireless leader who immersed himself in mountains of data, weighed all arguments, and often sweated profusely during rigorous decision-making sessions.

“He was calculating, an intelligent risk-taker, with very high expectations of himself and the people working for him,” said Geoffrey Rehnert, one of Bain Capital’s co-founders.

Bain made Romney fabulously wealthy. He has a net worth estimated at $250 million.

Romney consistently points to his Bain resume as proof of what he can accomplish, projecting an image of a take-charge businessman who understands what drives the economy and how to create jobs. According to Romney, his company created 100,000 new jobs (numbers that are difficult to verify), and helped grow such retail icons as Staples, The Sports Authority and Domino’s Pizza.

But, as his record at Bain has come under increasing scrutiny, it has also raised questions about Romney’s core values and style. The Obama campaign has accused Romney of being a job destroyer and “outsourcer in chief” for the factories that Bain closed and the jobs it moved abroad.

Rehnert says the attacks on Bain are offensive to those who worked there, and unfair to Romney because some of the deals that soured were not on his watch. He also dismissed a famous photograph of the early Bain team, with $10 and $20 bills bulging out of their pockets, and clenched between their teeth, as feeding into what he and others say is the biggest misconception about Romney: that he is only interested in money.

In fact, Rehnert said, Romney was so frugal that, although partners were earning vast sums, they worked at cheap metal desks and Romney once chided him for frivolously spending money on a newfangled toy: a cellphone. It was the mid-1980s.

Others described a big-hearted businessman who put family firmly first. In 1996, Romney shut down the company after a managing director’s 14-year-old daughter went missing after a party. The entire staff was dispatched to New York, where they fanned out with fliers and search teams. She eventually was found at a friend’s house.

This is the generous boss Cindy Gillespie remembers from the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City. Gillespie, later a top gubernatorial aide, hadn’t known Romney very long when her father lapsed into a coma after heart surgery. Romney, she said, called her at the hospital every day. Later, after her father recovered, Romney picked him to participate in the Olympic torch relay as the representative Vietnam veteran.

“It was the highlight of his life,” Gillespie said of her father.

Others testify to similar acts of kindness during Romney’s time as church leader in the 1980s and 1990s. Douglas Anderson, dean of the business school at Utah State University and a longtime family friend, describes how the Romneys opened their house to his family for a month after the Anderson house burned down. Others describe Romney piling his boys into his truck to help someone move house, fixing a church member’s leaking roof or tackling a hornet’s nest for a friend.

But there was also an authoritarian side that struck some as self-righteous and cold.

As a young bishop in 1983 Romney learned that a married mother of four in his ward had been advised by doctors to terminate her latest pregnancy as she was being treated for a potentially dangerous blood clot. Her stake president already had approved, when Romney arrived at the hospital and sternly urged her to reconsider. “As your bishop,” she said Romney told her, “my concern is with the child.”

Recalling the incident in Scott’s book, the woman, Carrel Hilton Sheldon said: “Mitt has many, many winning qualities but at the time he was blind to me as a human being.”

RETURNING FIRE

Romney often quotes a piece of advice from his father.

“Never get into politics too young,” he’d say. “Only after you’ve proven yourself somewhere else, and your kids are raised.”

Romney’s first foray into politics, in 1994, struck some as political insanity. Prodded by his father, Romney challenged Sen. Kennedy, the so-called “liberal lion” from Massachusetts, one of the most Democratic states. Romney presented himself as pro-choice, a champion for gay rights and in favor of gun control — among numerous positions he later reversed. The pundits accused him of trying to be “more Kennedy than Kennedy.”

Initially the squeaky-clean newcomer did well in the polls, unnerving the Kennedy campaign. But once the Kennedy machine swung into full gear, Romney’s campaign faltered. Foreshadowing the attack ads of today, Kennedy aggressively went after Romney’s record at Bain, casting him as a cold-hearted capitalist willing to do anything for profits. For the first time, Romney’s religion was also publicly scrutinized.

Romney, who refused to run negative ads against Kennedy, said later that he learned valuable lessons from his defeat, that “if fired upon, you return fire.”

Back at Bain, he was restless for a new challenge. It came in 1999 when Romney was recruited to, as he puts it, “rescue the Winter Olympics.” At the time, the 2002 games in Salt Lake City had become mired in a bribery scandal and faced a massive deficit. The organizing committee needed a white knight, and Romney eagerly hurled himself into the job.

But while many credit him with turning around the Olympics and invigorating a demoralized staff, others say he magnified the extent of the financial problems, unfairly vilified earlier executives and was as intent on promoting himself as much as the games. Romney’s image even appeared on a number of Olympic pins, which struck some as narcissistic.

“It was obvious that he had an agenda larger than just the Olympics,” Robert H. Garff, chairman of the organizing committee, said in 2007.

Sure enough, after a triumphant return to Boston, Romney wasted no time in launching his bid for governor of Massachusetts. He was sworn in on Jan. 2, 2003, placing his hand on the same Bible his father had used when he was sworn in as governor of Michigan.

Romney’s immediate task was to tackle a $3 billion budget deficit, and, according to Gillespie, he approached it with the same laser focus and open-minded approach he had used on the Olympic deficit.

“He doesn’t micromanage,” Gillespie said. “He gets strong people, starts a methodical review, asks questions about everything, gets clarity and makes his decision.”

Romney instituted a series of spending cuts and fee increases — critics equated them to taxes — for many state licenses and services. But his signature achievement was health care reform. Reaching out to Democratic leaders, Romney succeeded in passing a health care law that requires everyone in Massachusetts to buy insurance or pay a penalty. The law, which Romney signed with great pomp on the steps of Faneuil Hall with Kennedy at his side, became the model for the national version pushed by Obama and recently upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court — a law Romney has vowed to repeal if elected.

Even as governor, Romney acted more like a CEO than a politician and displayed an imperious side that annoyed old-timers. His office was cordoned off with velvet ropes and state troopers were posted at an elevator reserved solely for his use.

He had a testy relationship with the Democratic-controlled Legislature, and spent little time cultivating the usual social or political relationships of the office. There was a palpable sense that his one-term governorship was a springboard to loftier goals.

At a recent Obama rally on the Statehouse steps, Democratic legislator Pat Haddad suggested that, if Romney is elected president, “you’re gonna get the same guy who never wanted to engage the Legislature. He never wanted to look for new jobs; he was always only looking for his next job.”

Today, Romney is back on the trail in pursuit of that job — one that eluded him four years ago when he lost the Republican nomination to John McCain. This time around, he is noticeably more confident, and seems more comfortable in his own skin. Yet, as much as he tries to humanize himself by, for example, tweeting about Carl Jr.’s jalapeno chicken sandwich or his trip to a local barber, the 65-year-old candidate cannot shake the image of someone whose wealth and privileged life have insulated him from ordinary people.

Some of his off-the-cuff remarks haven’t helped, such as saying his wife “drives a couple of Cadillacs” and that he didn’t really follow NASCAR too closely but has some friends who are team owners. Nor have media reports about plans to quadruple the size of his $12 million waterfront house in La Jolla, Calif., plans that include a split-level garage with an elevator. Romney also owns homes in New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Utah.

Friends say such an image is utter distortion. In person, they say, Romney is warm and engaging, with a penchant for bursting into song. Romney singing “America the Beautiful” used to be a fixture of his early campaign appearances.

Philip Barlow, a professor of Mormon history at Utah State who served with him in church described a meeting years ago in which Romney glided backwards across the room in a perfect rendition of Michael Jackson’s “moon walk.”

“He just has a certain personality and style,” Barlow said, “Even when he’s relaxing at his beach house in shorts flipping burgers and joking, there is still an elegance or formality about him.”

Others see a kind of patrician entitlement, a sense that Romney feels superior to most, destined even, to hold the highest political office in the land.

Some observers simply don’t know what to think

Tony Kimball, who served as executive secretary during Romney’s stint as stake president, said that while he has tremendous respect and affection for his friend, he is baffled by the candidate’s ever-shifting positions on issues and his opaqueness on policy.

“I don’t have a clue who this guy is right now,” said Kimball, a retired professor of government and politics. “But he is not the person I worked with back in the ’80s and ’90s.”

Kimball said he will not be voting for Romney.

But family friend Douglas Anderson, a Democrat who voted for Obama in the last election, said he will vote for Romney.

“While I am very sympathetic to many of the goals of President Obama,” Anderson said, “I think Mitt Romney is an extraordinary individual with the capacity to make an enormous contribution to this country. And I am eager to see him have that chance.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story